One More for the Money

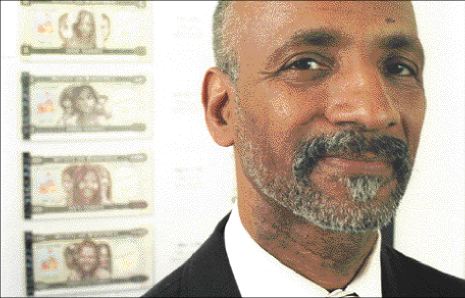

Clarence Holbert has made a career of having designs on currency.

In the basement of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, Clarence Holbert peers down at a display case filled with the landmarks of his 33-year career with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. The display, part of the exhibition “Art /Silver: 25 Years of Art at the University of the District of Columbia,” includes the Maryland designer’s Franklin Roosevelt stamp, several federal duck stamps and the Eritrean bank notes and coins he designed. Each is a fine example of Holbert’s art, rendered in precisely incised lines and vividly colored inks.

But to judge by the broad smile that stretches over Holbert’s thin face as he thumbs through a book of photographs he’s brought from the library’s second floor, the artist’s most cherished mementos aren’t under glass. The snapshots were taken on Nov. 8, 1997, the debut of Eritrea’s first currency since the small African country’s independence from Ethiopia. One of the pictures shows the capital city of Asmara with long strings of lights hanging above the town square, illuminating the dancing and singing below. Another shows Holbert posing with the young girl who graces the 10-nakfa bill.

Then Holbert gets to pictures of the lines, each hundreds of people deep. They’ve all been waiting for several hours, in small towns throughout Eritrea, to exchange their old Ethiopian money. Holbert pauses, looks up from the stack of photos, and temporarily abandons his trademark modesty. “They were awesomely proud of their currency,” he says.

Long before he ever dreamed of designing money, the 59-year-old Landover Hills resident spent every spare moment of his childhood scribbling. “If I made a mistake in my compositions, I’d draw a line through it and then turn that into a car or a ship or a train,” he recalls. “I’d imagine there are lots of crazy papers out there.” Not all of his sketching was done during class time, however: While attending grade school in the Northeast neighborhood of Ivy City, Holbert was often excused from his schoolwork so he could draw scenery for his school’s plays.

After high school, Holbert joined the military for four years, including one spent in Vietnam. When he returned to D.C., in 1968, he entered the lottery to become a student at the newly established Federal City College, which later became part of the University of the District of Columbia. Throughout these years, Holbert never neglected his artistic talent. “I had brothers and sisters who could draw,” he says. “But they never carried it to a full development, and then they couldn’t draw anymore. I was the only one who carried it through.”

[quoteicon author=”Charles E Holbert”]I feel like God blessed me with my career[/quoteicon]

Holbert excelled in Federal City’s art program, and he even had some success selling his paintings of such black-power figures as Angela Davis and Huey Newton. But he didn’t seriously consider pursuing a career as an artist until he discovered an unlikely stepping stone: a job in building security. While studying at the college, Holbert also worked full time as a security guard at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. There, he turned to art to shorten his long workdays.

“When I was a guard, anything that had a white surface, I would draw on it,” he says. “People came by, and they would collect them. Word got around.” Holbert’s reputation as a virtuoso doodler paid off with more than just the admiration of his co-workers: When a spot for an engraving apprenticeship opened up at the bureau, he was invited to take the position.

“Affirmative action was just starting, and they were looking for qualified Black candidates,” Holbert says. “I was in the right place at the right time.”Soon after his training began, Holbert was transferred from engraving to the design division. The curriculum of the seven-year program included, Holbert says, “everything there is to know about currency,” from drawing a compound curve to freehand lettering to creating security features: “After a while, you could lay it out perfectly by hand. I learned how to put currency together with just a pencil, pen, and ink. It was a rather intensive apprenticeship.”

Holbert’s mentor during his design studies was Ronald Sharp, the first Black bank-note designer. “He told me to keep a low key and to make sure my work was top, Grade A,” Holbert says. “He made sure that the things that were taught to others were taught to me.”

When, with Sharp’s guidance, Holbert earned his journeyman’s certificate in 1975, he became the second Black currency designer. “There was sometimes that I was kind of discouraged in it, but I never thought of quitting,” Holbert says. “When I had a chance to move up, everyone was behind me–security guards, janitors, postal workers. They were like, ‘We made it.’ It got to be a we thing.”

In three decades as an Engraving and Printing designer, Holbert shared the caseload with four other journeymen. “We did ID cards for the CIA and the FBI, the Purple Hearts, different citations, personal invitations to the White House, passports–everything,” he says.

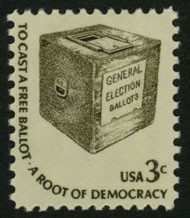

For the 3-cent ballot-box stamp he created for the U.S. Postal Service’s Americana series in 1977, Holbert researched early boxes, found a picture that he liked, and then created a pointillist rendition at stamp scale. After making the small drawing, he enlarged it to five times its actual size to sharpen small details, then reduced this larger version to create the final design at philatelic dimensions and complete with perforations.

For the 3-cent ballot-box stamp he created for the U.S. Postal Service’s Americana series in 1977, Holbert researched early boxes, found a picture that he liked, and then created a pointillist rendition at stamp scale. After making the small drawing, he enlarged it to five times its actual size to sharpen small details, then reduced this larger version to create the final design at philatelic dimensions and complete with perforations.

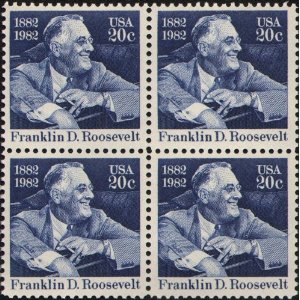

Among the stamps he designed, the 13-cent FDR is particularly memorable for Holbert: His choice of a portrait depicting the former president wielding a cigarette holder caused a Fat Elvis vs. Skinny Elvis-esque controversy. “I got a lot of correspondence speaking ill of it,” he says. “They were surprised at the audacity to show him smoking. The post office gave me grief for it, too.” Nevertheless, Holbert held firm in his refusal to doctor the painting, and he eventually won out. “I got to go up to Hyde Park, and [I] met quite a few different people,” he says. “Rockefellers, Carnegies…the money.”

Among the stamps he designed, the 13-cent FDR is particularly memorable for Holbert: His choice of a portrait depicting the former president wielding a cigarette holder caused a Fat Elvis vs. Skinny Elvis-esque controversy. “I got a lot of correspondence speaking ill of it,” he says. “They were surprised at the audacity to show him smoking. The post office gave me grief for it, too.” Nevertheless, Holbert held firm in his refusal to doctor the painting, and he eventually won out. “I got to go up to Hyde Park, and [I] met quite a few different people,” he says. “Rockefellers, Carnegies…the money.”

Despite such successes, Holbert long hoped for a chance to put his bank-note-making knowledge to use. His assignment at the bureau, however, was to the miscellaneous file, the typical destination for noncurrency assignments. Holbert did help redesign the military’s payment certificates and craft several different test designs for American currency, but for years, he saw most money-related projects go to his colleagues. So when an anomalous request to design the Eritrean currency came to him as part of the miscellany in 1994, the excited Holbert immediately headed to Howard University to do research. “[The Eritreans] were really in love with our money, so that’s why they came to our country [with the commission],” he says. Not long after Holbert started the assignment, the Eritrean government supplemented his study by presenting him with more than 100 photographs of the country. “There were pictures of everything,” Holbert says. “From people plowing to landscapes with camels, farmers working in the fields, children studying–just anything.”

By the end of the project, Holbert had had the opportunity to visit Eritrea four separate times. “Every time I went, they would give me an escort and a driver,” he says. “We were just allowed to see what they look like, see the uniqueness of the country, and meet the basic people.”

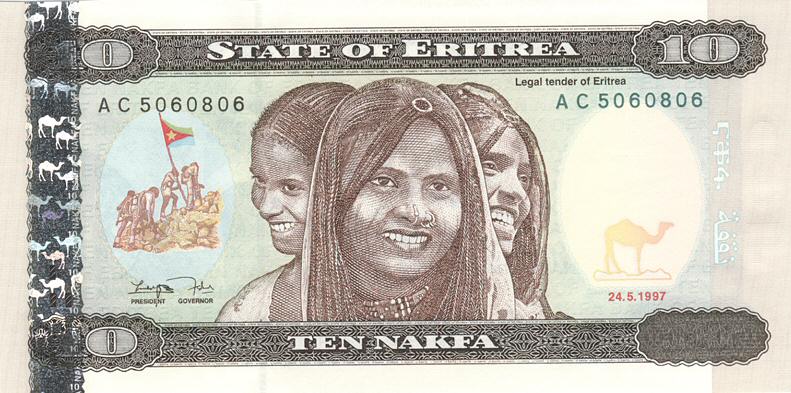

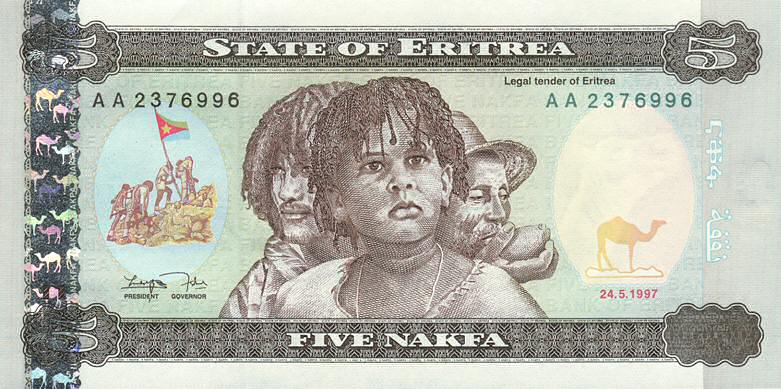

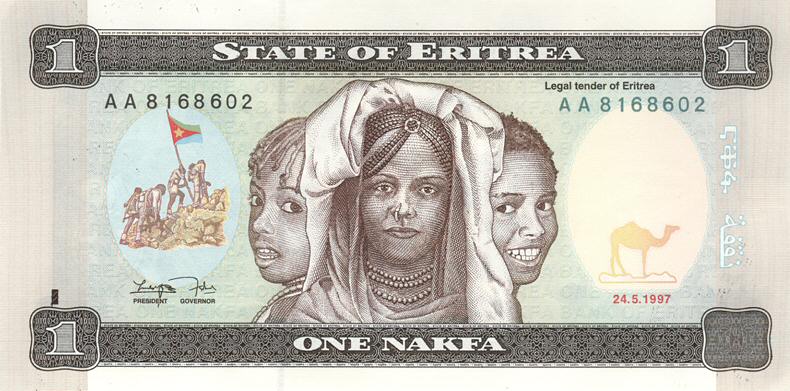

Holbert’s final designs reflected the concept of national unity, the desire to reach forward while honoring the past, and…the inspirational powers of a bologna sandwich. When he sat down for lunch one day several months into the project, Holbert had already completed two designs but wasn’t completely satisfied with the convention of a single face in the center of each bill. Over his sandwich, an idea came to him: Each bill would contain a triptych–one face in the center, with two more in profile on each side. He quickly sketched the design on a napkin, then ran back to his office to finalize it.

A few weeks after these sketches were sent to Eritrea by messenger in September 1996, Holbert received the blessings of Eritrean President Isaias Afworki and his cabinet, who noted that the artist had happened to choose people from all nine of Eritrea’s ethnic groups to appear on the six different coins and six different bills. The pastel obverse of each paper denomination, rendered in colors beyond the range of a typical color copier, is a concession to security, but the reverses of the bills are the distinctive green of American dollars. “They wanted something in some way similar,” Holbert says. “They liked how the United States has that one basic color.”

On the front of each note is a small drawing of the raising of the Eritrean flag during the decisive battle for the country’s independence. The money takes its name, the nakfa, from the site of this conflict. “This was kind of personal because, just the magnitude of it,” says Holbert. “This is a new country coming into being. Being here in the United States, and working on currency, it gave me the chance to think about what it must have been like for the first designers.”

Holbert’s finest moment as a bank-note designer was also his last: The Eritrean project was his final assignment before his retirement, in 1998. He’s now heavily involved in his church and is thinking about going back to UDC to finish up the few courses he needs to get his college degree. In the meantime, he’s working on two potential book projects: a history of black bank-note designers and the story of his experiences in Eritrea.

The country still has a hold on Holbert. He calls the Eritrean Embassy regularly to see “how everyone is doing and how my money’s doing,” he says. “I haven’t gotten any complaints yet.” He’s also had a job offer there: When he told Eritrean officials during his last visit that he was retiring, they offered to build him a facility and furnish him with any equipment that he desired in exchange for training several Eritreans in the art of bank-note design.

Although his wife doesn’t like to travel, Holbert is considering the idea, and he’s also interested in designing money for any country–especially any African one–that is willing to give him a commission. For now, though, Holbert is happy to think of his work for Eritrea as his legacy.

“I knew I had a stamp down at the Smithsonian that I had designed,” he says. “But this is more unique to me than actually having a picture in a gallery, which is every artist’s dream, because this is something that’s used every day. Most people think about it more than I do. It’s an interesting thing to just happen.”

Source: Josh Levin, Washington City Paper, 2003

[line-sep]

[intro-paragraph]First Black Director of the U.S. Bureau of Engraving[/intro-paragraph]

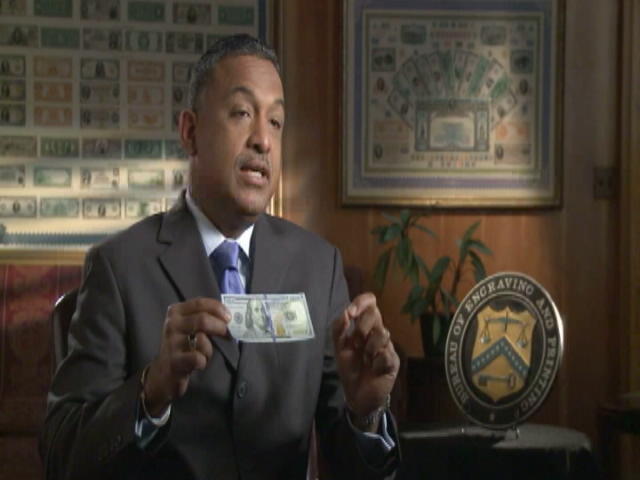

Larry R. Felix, the first Black director of the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP), recently made his first public appearances in his new position. Felix was joined by officials of the Department of the Treasury, Federal Reserve Board, U.S. Secret Service and National Archives as he introduced the newly re-designed $10 bill at a recent press conference in Washington, D.C.

Felix was named director of the BEP by Secretary of the Treasury John W. Snow.

As director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Felix is responsible for the overall operations of the Bureau in the production of U.S. currency and other government securities and documents. In order to stay ahead of counterfeiters, the U.S. government is redesigning the currency every seven to 10 years.

Source: 2006 Johnson Publishing Co.