Pre-Boomerang/Cartoon Network, when there were only three major networks (CBS, NBC and ABC), part of the television ritual for kids during the 1970s was Saturday morning cartoons.

Indeed, while I could sleep like a rock on school day mornings, ignoring both the alarm and my mother’s high-pitched screams, on Saturday mornings I was up at dawn, transfixed in front of the boob tube.

Of course I had no idea that the cartoon racket was merely set up to sell kids sugary cereals and cheap toys, because I was too busy having misadventures with the Wacky Racers, roaming through haunted houses with Scooby-Doo and bopping to the cool Henry Mancini music on The Pink Panther.

While in my 1960s childhood, most of the human characters were still White (with the exception of a few racist Warner Bros. shorts), an absolute revelation occurred in Toontown by 1970. After the demonstrations, riots and deaths of the civil-rights era, surprisingly one the first fertile grounds of that mixed integration and imagination was found in animation programming.

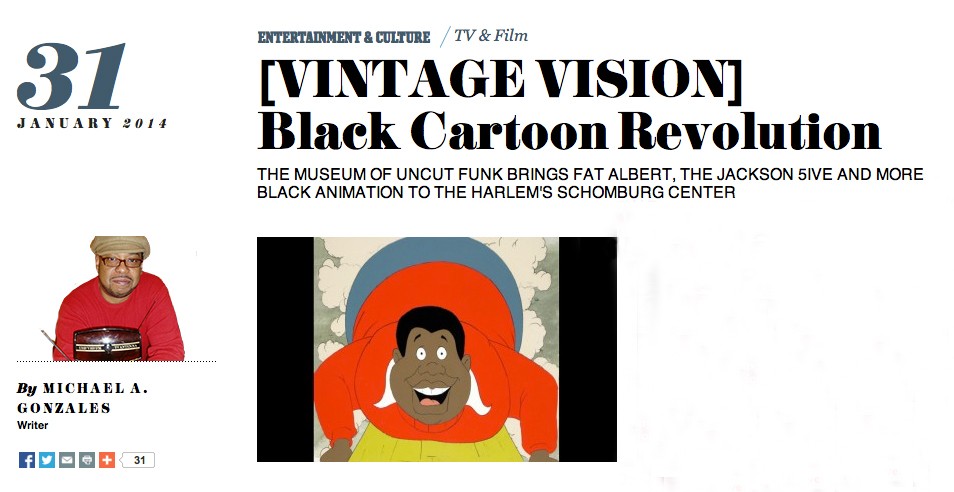

With Fat Albert, the Harlem Globetrotters, the Jackson 5 and Valerie Brown from Josie and the Pussycats broadcast into our lives on a weekly basis, we were watching a revolution without realizing it.

“These cartoons changed the lives of a generation of children,” says Museum of UnCut Funk co-curator Pamela Thomas. Along with her business partner Loreen Williamson, she began collecting animation cels (the transparent sheets on which objects were drawn or painted for animation in the days before computers) to add to their collection of Black memorabilia that includes blaxploitation posters, comic books and advertising art. “We feel these cartoons are national treasures, and it’s up to us to get the word out.”

Opening February 5 at Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Thomas and Williamson’s much anticipated animation exhibit—The Funky Turns 40: Black Character Revolution—includes 60 pieces of animation art from their Museum Of UnCut Funk collection. A fun, colorful, nostalgic experience culturally and historically relevant for the Black community, the show will also appeal to a broader audience who takes this brand of pop culture seriously. The show closes in mid June.

Read more at EBONY http://www.ebony.com/entertainment-culture/vintage-vision-black-cartoon-revolution-333#ixzz2srlOm55q

Cultural critic Michael A. Gonzales has written cover stories for Vibe, Uptown, Essence, XXL, Wax Poetics and elsewhere. He’s also written for New York and The Village Voice. Read him at Blackadelic Pop and follow him on Twitter @gonzomike.