For Immediate Release

May 14, 2009

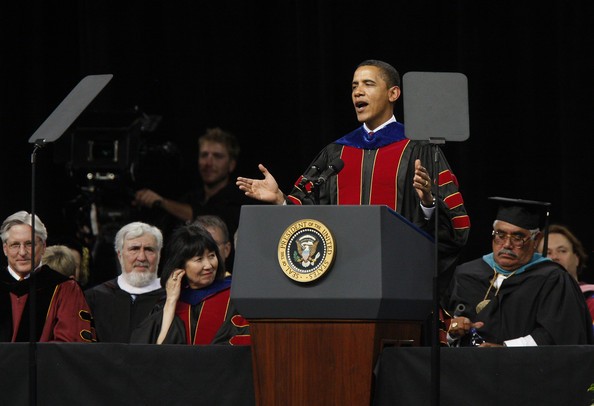

REMARKS BY THE PRESIDENT

AT ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT

Sun Devil Stadium

Tempe, Arizona

May 13, 2009

7:59 P.M. MST

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you, ASU. (Applause.) Thank you very much. Thank you very much. Thank you so much. Thank you — please. Well, thank you, President Crow, for that extremely generous introduction, for your inspired leadership as well here at ASU. And I want to thank the entire ASU community for the honor of attaching my name to a scholarship program that will help open the doors of higher education to students from every background. What a wonderful gift. Thank you. (Applause.) That notion of opening doors of opportunity to everybody, that is the core mission of this school; it’s a core mission of my presidency; and I hope this program will serve as a model for universities across this country. So thank you so much. (Applause.)

I want to obviously congratulate the Class of 2009 you’re your unbelievable achievement. (Applause.) I want to thank the parents, the uncles, the grandpas, the grandmas, cousins — Calabash cousins — everybody who was involved in helping these extraordinary young people arrive at this moment. I also want to apologize to the entire state of Arizona for stealing away your wonderful former governor, Janet Napolitano. (Applause.) But you’ve got a fine governor here and I also know that Janet is applying her extraordinary talents to serve our entire country as the Secretary of Homeland Security, keeping America safe. And she’s doing a great job. (Applause.)

Now, before I begin, I’d just like to clear the air about that little controversy everybody was talking about a few weeks back. I have to tell you, I really thought this was much ado about nothing, but I do think we all learned an important lesson. I learned never again to pick another team over the Sun Devils in my NCAA bracket. (Applause.) It won’t happen again. President Crow and the Board of Regents will soon learn all about being audited by the IRS. (Laughter and applause.)

Now, in all seriousness, I come here not to dispute the suggestion that I haven’t yet achieved enough in my life. (Laughter.) First of all, Michelle concurs with that assessment. (Laughter.) She has a long list of things that I have not yet done waiting for me when I get home. But more than that, I come to embrace the notion that I haven’t done enough in my life; I heartily concur; I come to affirm that one’s title, even a title like President of the United States, says very little about how well one’s life has been led — that no matter how much you’ve done, or how successful you’ve been, there’s always more to do, always more to learn, and always more to achieve. (Applause.)

And I want to say to you today, graduates, Class of 2009, that despite having achieved a remarkable milestone in your life, despite the fact that you and your families are so rightfully proud, you too cannot rest on your laurels. Not even some of those remarkable young people who were introduced earlier — not even that young lady who’s got four degrees yet today. You can’t rest. Your own body of work is also yet to come.

Now, some graduating classes have marched into this stadium in easy times — times of peace and stability when we call on our graduates simply to keep things going, and don’t screw it up. (Laughter.) Other classes have received their diplomas in times of trial and upheaval, when the very foundations of our lives, the old order has been shaken, the old ideas and institutions have crumbled, and a new generation is called upon to remake the world.

It should be clear to you by now the category into which all of you fall. For we gather here tonight in times of extraordinary difficulty, for the nation and for the world. The economy remains in the midst of a historic recession, the worst we’ve seen since the Great Depression; the result, in part, of greed and irresponsibility that rippled out from Wall Street and Washington, as we spent beyond our means and failed to make hard choices. (Applause.) We’re engaged in two wars and a struggle against terrorism. The threats of climate change, nuclear proliferation, and pandemic defy national boundaries and easy solutions.

For many of you, these challenges are also felt in more personal terms. Perhaps you’re still looking for a job — or struggling to figure out what career path makes sense in this disrupted economy. Maybe you’ve got student loans — no, you definitely have student loans — (applause) — or credit card debts, and you’re wondering how you’ll ever pay them off. Maybe you’ve got a family to raise, and you’re wondering how you’ll ensure that your children have the same opportunities you’ve had to get an education and pursue their dreams.

Now, in the face of these challenges, it may be tempting to fall back on the formulas for success that have been pedaled so frequently in recent years. It goes something like this: You’re taught to chase after all the usual brass rings; you try to be on this “who’s who” list or that top 100 list; you chase after the big money and you figure out how big your corner office is; you worry about whether you have a fancy enough title or a fancy enough car. That’s the message that’s sent each and every day, or has been in our culture for far too long — that through material possessions, through a ruthless competition pursued only on your own behalf — that’s how you will measure success.

Now, you can take that road — and it may work for some. But at this critical juncture in our nation’s history, at this difficult time, let me suggest that such an approach won’t get you where you want to go; it displays a poverty of ambition — that in fact, the elevation of appearance over substance, of celebrity over character, of short-term gain over lasting achievement is precisely what your generation needs to help end. (Applause.)

Now, ASU, I want to highlight — I want to highlight two main problems with that old, tired, me-first approach. First, it distracts you from what’s truly important, and may lead you to compromise your values and your principles and commitments. Think about it. It’s in chasing titles and status — in worrying about the next election rather than the national interest and the interests of those who you’re supposed to represent — that politicians so often lose their ways in Washington. (Applause.) They spend time thinking about polls, but not about principle. It was in pursuit of gaudy short-term profits, and the bonuses that came with them, that so many folks lost their way on Wall Street, engaging in extraordinary risks with other people’s money.

In contrast, the leaders we revere, the businesses and institutions that last — they are not generally the result of a narrow pursuit of popularity or personal advancement, but of devotion to some bigger purpose — the preservation of the Union or the determination to lift a country out of a depression; the creation of a quality product, a commitment to your customers, your workers, your shareholders and your community. A commitment to make sure that an institution like ASU is inclusive and diverse and giving opportunity to all. That’s a hallmark of real success. (Applause.)

That other stuff — that other stuff, the trappings of success may be a byproduct of this larger mission, but it can’t be the central thing. Just ask Bernie Madoff. That’s the first problem with the old attitude.

But the second problem with the old approach to success is that a relentless focus on the outward markers of success can lead to complacency. It can make you lazy. We too often let the external, the material things, serve as indicators that we’re doing well, even though something inside us tells us that we’re not doing our best; that we’re avoiding that which is hard, but also necessary; that we’re shrinking from, rather than rising to, the challenges of the age. And the thing is, in this new, hyper-competitive age, none of us — none of us — can afford to be complacent.

That’s true in whatever profession you choose. Professors might earn the distinction of tenure, but that doesn’t guarantee that they’ll keep putting in the long hours and late nights — and have the passion and the drive — to be great educators. The same principle is true in your personal life. Being a parent is not just a matter of paying the bills, doing the bare minimum — it’s not bringing a child into the world that matters, but the acts of love and sacrifice it takes to raise and educate that child and give them opportunity. (Applause.) It can happen to Presidents, as well. If you think about it, Abraham Lincoln and Millard Fillmore had the very same title, they were both Presidents of the United States, but their tenure in office and their legacy could not be more different.

And that’s not just true for individuals — it’s also true for this nation. In recent years, in many ways, we’ve become enamored with our own past success — lulled into complacency by the glitter of our own achievements.

We’ve become accustomed to the title of “military super-power,” forgetting the qualities that got us there — not just the power of our weapons, but the discipline and valor and the code of conduct of our men and women in uniform. (Applause.) The Marshall Plan, and the Peace Corps, and all those initiatives that show our commitment to working with other nations to pursue the ideals of opportunity and equality and freedom that have made us who we are. That’s what made us a super power. (Applause.)

We’ve become accustomed to our economic dominance in the world, forgetting that it wasn’t reckless deals and get-rich-quick schemes that got us where we are, but hard work and smart ideas — quality products and wise investments. We started taking shortcuts. We started living on credit, instead of building up savings. We saw businesses focus more on rebranding and repackaging than innovating and developing new ideas that improve our lives.

All the while, the rest of the world has grown hungrier, more restless — in constant motion to build and to discover — not content with where they are right now, determined to strive for more. They’re coming.

So graduates, it’s now abundantly clear that we need to start doing things a little bit different. In your own lives, you’ll need to continuously adapt to a continuously changing economy. You’ll end up having more than one job and more than one career over the course of your life; to keep gaining new skills — possibly even new degrees; and you’ll have to keep on taking risks as new opportunities arise.

And as a nation, we’ll need a fundamental change of perspective and attitude. It’s clear that we need to build a new foundation — a stronger foundation — for our economy and our prosperity, rethinking how we grow our economy, how we use energy, how we educate our children, how we care for our sick, how we treat our environment. (Applause.)

Many of our current challenges are unprecedented. There are no standard remedies, no go-to fixes this time around. And Class of 2009 that’s why we’re going to need your help. We need young people like you to step up. We need your daring, we need your enthusiasm and your energy, we need your imagination.

And let me be clear, when I say “young,” I’m not just referring to the date of your birth certificate. I’m talking about an approach to life — a quality of mind and quality of heart; a willingness to follow your passions, regardless of whether they lead to fortune and fame; a willingness to question conventional wisdom and rethink old dogmas; a lack of regard for all the traditional markers of status and prestige — and a commitment instead to doing what’s meaningful to you, what helps others, what makes a difference in this world. (Applause.)

That’s the spirit that led a band of patriots not much older than most of you to take on an empire, to start this experiment in democracy we call America. It’s what drove young pioneers west, to Arizona and beyond; it’s what drove young women to reach for the ballot; what inspired a 30 year-old escaped slave to run an underground railroad to freedom — (applause) — what inspired a young man named Cesar to go out and help farm workers; what inspired a 26 year-old preacher to lead a bus boycott for justice. It’s what led firefighters and police officers in the prime of their lives up the stairs of those burning towers; and young people across this country to drop what they were doing and come to the aid of a flooded New Orleans. It’s what led two guys in a garage — named Hewlett and Packard — to form a company that would change the way we live and work; what led scientists in laboratories, and novelists in coffee shops to labor in obscurity until they finally succeeded in changing the way we see the world.

That’s the great American story: young people just like you, following their passions, determined to meet the times on their own terms. They weren’t doing it for the money. Their titles weren’t fancy — ex-slave, minister, student, citizen. A whole bunch of them didn’t get honorary degrees. (Laughter and applause.) But they changed the course of history — and so can you ASU, so can you Class of 2009. (Applause.) So can you.

With a degree from this outstanding institution, you have everything you need to get started. You’ve got no excuses. You have no excuses not to change the world. Did you study business? (Applause.) Go start a company. (Applause.) Or why not help our struggling non-profits find better, more effective ways to serve folks in need. (Applause.) Did you study nursing? (Applause.) Understaffed clinics and hospitals across this country are desperate for your help. Did you study education? (Applause.) Teach in a high-need school where the kids really need you; give a chance to kids who can’t– who can’t get everything they need maybe in their neighborhood, maybe not even in their home we can’t afford to give up on — prepare them to compete for any job anywhere in the world. (Applause.) Did you study engineering? (Applause.) Help us lead a green revolution — (applause) — developing new sources of clean energy that will power our economy and preserve our planet.

But you can also make your mark in smaller, more individual ways. That’s what so many of you have already done during your time here at ASU — tutoring children; registering voters; doing your own small part to fight hunger and homelessness, AIDS and cancer. One student said it best when she spoke about her senior engineering project building medical devices for people with disabilities in a village in Africa. Her professor showed a video of the folks they’d been helping, and she said, “When we saw the people on the videos, we began to feel a connection to them. It made us want to be successful for them.” Think about that: “It made us want to be successful for them.”

That’s a great motto for all of us — find somebody to be successful for. Raise their hopes. Rise to their needs. As you think about life after graduation, as you look into the mirror tonight after the partying is done — (laughter and applause) — that shouldn’t get such a big cheer — (laughter) — you may look in the mirror tonight and you may see somebody who’s not really sure what to do with their lives. That’s what you may see, but a troubled child might look at you and see a mentor. A homebound senior citizen might see a lifeline. The folks at your local homeless shelter might see a friend. None of them care how much money is in your bank account, or whether you’re important at work, or whether you’re famous around town — they just know that you’re somebody who cares, somebody who makes a difference in their lives.

So Class of 2009, that’s what building a body of work is all about — it’s about the daily labor, the many individual acts, the choices large and small that add up over time, over a lifetime, to a lasting legacy. That’s what you want on your tombstone. It’s about not being satisfied with the latest achievement, the latest gold star — because the one thing I know about a body of work is that it’s never finished. It’s cumulative; it deepens and expands with each day that you give your best, each day that you give back and contribute to the life of your community and your nation. You may have setbacks, and you may have failures, but you’re not done — you’re not even getting started, not by a long shot.

And if you ever forget that, just look to history. Thomas Paine was a failed corset maker, a failed teacher, and a failed tax collector before he made his mark on history with a little book called “Common Sense” that helped ignite a revolution. (Applause.) Julia Child didn’t publish her first cookbook until she was almost 50. Colonel Sanders didn’t open up his first Kentucky Fried Chicken until he was in his 60s. Winston Churchill was dismissed as little more than a has-been, who enjoyed scotch a little bit too much, before he took over as Prime Minister and saw Great Britain through its finest hour. No one thought a former football player stocking shelves at the local supermarket would return to the game he loved, become a Super Bowl MVP, and then come here to Arizona and lead your Cardinals to their first Super Bowl. (Applause.) Your body of work is never done.

Each of them, at one point in their life, didn’t have any title or much status to speak of. But they had passion, a commitment to following that passion wherever it would lead, and to working hard every step along the way.

And that’s not just how you’ll ensure that your own life is well-lived. It’s how you’ll make a difference in the life of our nation. I talked earlier about the selfishness and irresponsibility on Wall Street and Washington that rippled out and led to so many of the problems that we face today. I talked about the focus on outward markers of success that can help lead us astray.

But here’s the thing, Class of 2009: It works the other way around too. Acts of sacrifice and decency without regard to what’s in it for you — that also creates ripple effects — ones that lift up families and communities; that spread opportunity and boost our economy; that reach folks in the forgotten corners of the world who, in committed young people like you, see the true face of America: our strength, our goodness, our diversity, our enduring power, our ideals.

I know starting your careers in troubled times is a challenge. But it is also a privilege. Because it’s moments like these that force us to try harder, to dig deeper, and to discover gifts we never knew we had — to find the greatness that lies within each of us. So don’t ever shy away from that endeavor. Don’t stop adding to your body of work. I can promise that you will be the better for that continued effort, as will this nation that we all love.

Congratulations, Class of 2009, on your graduation. God bless you. And God bless the United States of America. (Applause.)