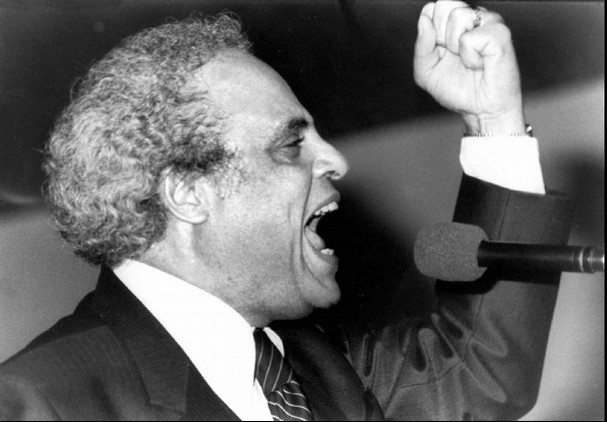

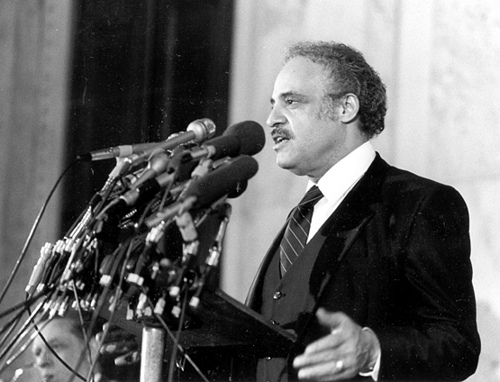

Mr. Hooks told Ebony magazine soon after he became the association’s executive director in 1977. “The civil rights movement is not dead. “If anyone thinks that we are going to stop agitating, they had better think again. If anyone thinks that we are going to stop litigating, they had better close the courts. If anyone thinks that we are not going to demonstrate and protest, they had better roll up the sidewalks.”

Yet under his leadership the N.A.A.C.P. faced a growing white backlash against school busing and affirmative action programs intended to redress past discrimination. And it repeatedly tangled with the administrations of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush to preserve the gains that minorities had made in the 1960s and ’70s. When Mr. Bush selected a conservative black federal judge, Clarence Thomas, to serve on the Supreme Court, the N.A.A.C.P. ultimately opposed the nomination.

“I’ve had the misfortune of serving eight years under Reagan and three under Bush,” Mr. Hooks said in 1992, the year he stepped down as executive director. “It makes a great deal of difference about your expectations. We’ve had to get rid of a lot of programs we had hoped for, so we could fight to save what we already had.”

Mr. Hooks shifted much of the N.A.A.C.P.’s focus to increasing educational and job opportunities for blacks as recession gave way to economic recovery in the Reagan years. But the association had been weakened under the weight of declining membership and shaky finances.

It had also developed an image problem, as that of an outmoded and increasingly irrelevant civil rights group. For some who had watched the N.A.A.C.P. over the years, Mr. Hooks came to symbolize an older generation of leaders who had marched with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and who had fought for the passage of landmark civil rights legislation but who had become unwilling or unable to adapt to modern times and changed political circumstances.

Mr. Hooks rejected that notion, maintaining that he had succeeded in advancing a just cause, to improve the lot of African-Americans. “I have fought the good fight,” he said in his valedictory to the N.A.A.C.P. in 1992. “I have kept the faith.”

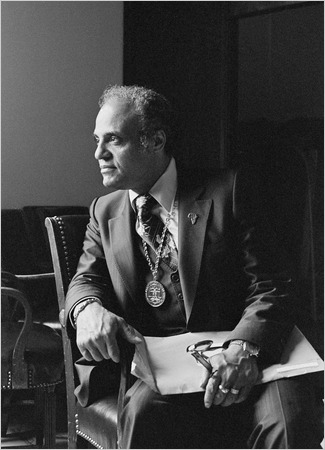

Mr. Hooks had a varied career. He was a lawyer, a businessman and a Baptist minister, heading two separate churches. He was also a gifted orator, mixing quotations from Shakespeare and Keats with the cadence and idioms of the Mississippi Delta.

“There is a beauty in it and a power in it,” Mr. Hooks once said of black preachers’ speaking style.

Mr. Hooks was the first black to be appointed to the criminal court bench in his native Tennessee, and he was the first African-American to be named to the five-member Federal Communications Commission.

“Most people do one or two things in their lifetimes,” Julian Bond, a former chairman of the N.A.A.C.P., said of Mr. Hooks. “He’s just done an awful lot.”

Benjamin Lawson Hooks was born Jan. 31, 1925, in Memphis, the fifth of seven children of Robert and Bessie Hooks. His father’s photography business gave the family a stable middle-class grounding, allowing Mr. Hooks to attend LeMoyne College in Memphis. Mr. Hooks died on April 25, 2010.

Source: Associated Press