Sissieretta Jones aka Black Patti (1869-1933) was a pioneer of Black operatic singing, and she paved the way for a long list of black opera singers to follow, including Marian Anderson, Roland Hayes, Leontyne Price, and Grace Bumbry, among others.

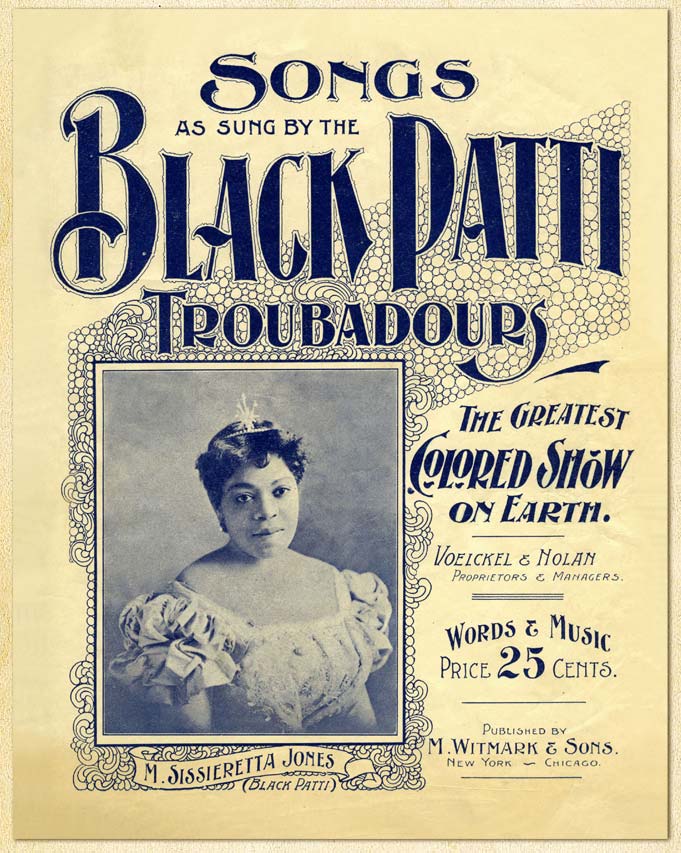

From 1890 to 1916, Sissieretta Jones was one of the best-known and highest-paid Black singers in America. She sang for U.S. presidents and for royalty in Europe, and drew sellout crowds with her own minstrel show, Black Patti’s Troubadors. But she died nearly penniless in Providence. Born in Virginia in 1869, Matilda Sissieretta Joyner was the daughter of a minister of the African Methodist Church. The family moved to Providence in 1876, and Sissieretta attended Meeting Street and Thayer Schools in Providence.

From an early age, she sang for the public – at school functions and festivals at Pond Street Church. She married in 1883 when she was only 14, and had one child, Mabel, who died before the age of 2. Her husband, David Richmond Jones, was her manager for several years but apparently squandered and mismanaged her money. They divorced in 1899.

When she was 18, she attended the New England Conservatory in Boston, one of the best music schools in America.By 1887, Sissieretta had begun to draw public acclaim, appearing in front of 5,000 people at Boston’s Music Hall in a benefit for the Parnell Defence Fund. In 1888, she made her successful New York debut and was engaged to tour the West Indies with a Black troupe. During that tour, she was presented with the first of many medals she was often photographed wearing.

As Sissieretta’s fame grew, she began to be known as “The Black Patti,” a phrase coined by a New York City newspaper, comparing her to the great Italian opera singer Adelina Patti. Although Sissieretta reportedly disliked the name, it remained with her throughout her career. In 1892, she sang for President Banjamin Harrison in the White House and starred in the Grand African Jubilee, a three-day event at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

After she signed a three-year contract with Maj. J.B. Pond, a manager of other well-known singers and lecturers such as Mark Twain and the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, Jones’s fees began to rise. She was paid $2,000 for a week’s appearance at the Pittsburgh Exposition, the highest fee ever paid to a Black artist. (By comparison, Adelina Patti was paid $4,000 a night.) After legal troubles involving her husband’s attempt to book appearances for her independent of Pond, Jones went to Europe for an extended tour.

She sang for the Prince of Wales and the Kaiser, and in a letter home said that she encountered much less racial prejudice in Europe. “It matters not to them what is the color of an artist’s skin,” she wrote. “If a man or a woman is a great actor, or a great musician, or a great singer, they will extend a warm welcome. . . . It is the soul they see, not the color of the skin.”

In 1896, Jones formed her own touring company, Black Patti’s Troubadors, which toured for the next 20 years, playing Black and white audiences alike. The show included Jones’s singing as well as vaudeville and minstrel acts. Around 1916, she retired to her home in Providence. By the time she died in 1933, her savings were nearly gone and she had sold three of her four houses and most of her jewels and medals. In her final years, William Freeman, a real estate agent and president of the local chapter of the NAACP, paid her taxes, water bill and provided coal and wood.

Contributor: Jane Lancaster

1 Comment

Blown away!