Janet MacLachlan, who played the compassionate schoolteacher in Martin Ritt’s Oscar-nominated “Sounder” (1972), has died at age 77. A highly respected stage, film and television actress, Maclachlan was known for a serious, no-nonsense style that led her to be often cast as a judge, nurse, doctor, psychiatrist, teacher or social worker. She was highly visible during the transitional period of the 1960s and 70s, when African-Americans fought against negative stereotypes on screen and began to make significant inroads in front of and behind the cameras.

MacLachlan died Monday, October 11 at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in Hollywood. She had been admitted two days earlier suffering from cardiac symptoms, family members said.

She was born Janet Angel MacLachlan in Harlem on August 27, 1933, to James and Ruby MacLachlan, both Jamaican immigrants. She attended the all-girl Julia Richman High School and excelled in math, graduating in 1950. According to a New York Times interview, it was in high school that Maclachlan “felt Black” for the first time, as there were only three other African-American students on campus. “It was very strange because I had come from an all-Black school and I didn’t know how to deal with it,” she said. MacLachlan’s first acting experience was in a Harlem Boys Club play, as a teen. Later, while she was attending Hunter College, she studied drama in a private class taught by Sidney Poitier, who instilled in her not only the importance of refining her craft but also of developing a point of view. “He had a tendency to lecture me because I had no attitudes and no beliefs and I was very wishy-washy,” she once recalled. “He wanted me to help find out who I was and not to let people tell me what to do.”

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in psychology in 1955, MacLachlan worked at clerical jobs while studying acting at the Harlem YMCA, the Herbert Berghof Acting Studio and the Little Theatre of Harlem. After a few years she had worked her way up to become an executive secretary and office manager for a New York public relations firm, but the business world was unsatisfying and she felt the calling of the stage. In 1961, MacLachlan impulsively gave up her job and its then-decent salary of $175 per week and traded it for a $5-a-week stipend to understudy Cicely Tyson in two productions simultaneously: “Moon on a Rainbow Shawl” and Jean Genet’s controversial off-Broadway play, “The Blacks: A Clown Show.” After Tyson’s departure from “The Blacks,” MacLachlan played the role of Virtue, the prostitute, for six weeks, working alongside such acclaimed and established actors as James Earl Jones, Louis Gossett, Jr., Maya Angelou and Roscoe Lee Browne. Suddenly her acting career was off and running. That same year she appeared in the parody “Raisin’ Hell in the Son” and was called the “most memorable member of the cast” by a New York Times reviewer.

Robert Hooks, who portrayed Deodatus Village (a role first played by James Earl Jones) in “The Blacks,” remembered MacLachlan as “…a brilliant woman and a great individual and super talent. I always admired her acting ability, and just as a strong black woman she was there all the way. Not necessarily a feminist but just a strong black woman with strong beliefs about feminism. There was a pridefulness in her work, and she refused to do the silly stuff. “She played the role of Virtue, a role that Cicely Tyson originated, and that’s when I got so taken with her,” Hooks continued. “It was probably the meatiest role she’s ever done, because she was one of those actresses who never really got the big shot, the Cicely Tyson-type shot as an artist, but when she did do the roles she mastered them. We had a wonderful time, because most of our scenes were together. I witnessed the depth of her character study, and I was right there on the stage with her when she was doing it.”

MacLachlan made her Broadway debut in December 1962 in Peter Feibleman’s “Tiger, Tiger Burning Bright” at the Booth Theater; the cast featured an array of established and up-and-coming black thespians from the New York stage, including Roscoe Lee Browne, Al Freeman Jr., Rudy Challenger, Ellen Holly, Diana Sands, Claudia McNeil, as well as Tyson and Hooks. MacLachlan then spent time with the repertory company at the Tyrone Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, honing her craft by appearing in “Hamlet,” “Death of a Salesman” and “The Miser.”

By 1964 she had moved to Hollywood and was signed by Universal as a contract player. MacLachlan had one-shot parts on TV series such as “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour,” “Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theater,” “The Girl From U.N.C.L.E.” and “The Fugitive.” Through the late 1960s and early 70s she appeared on “The Invaders,” “The FBI,” “Ironside,” “The Mod Squad,” The Name of the Game” and other series. Two of her best TV roles, both of which aired in 1967, are an African girl in an episode of “I Spy” with Bill Cosby, which was shot on location in Greece, and a first-season episode of “Star Trek” in which MacLachlan played an Enterprise crewmember named Lt. Charlene Masters.

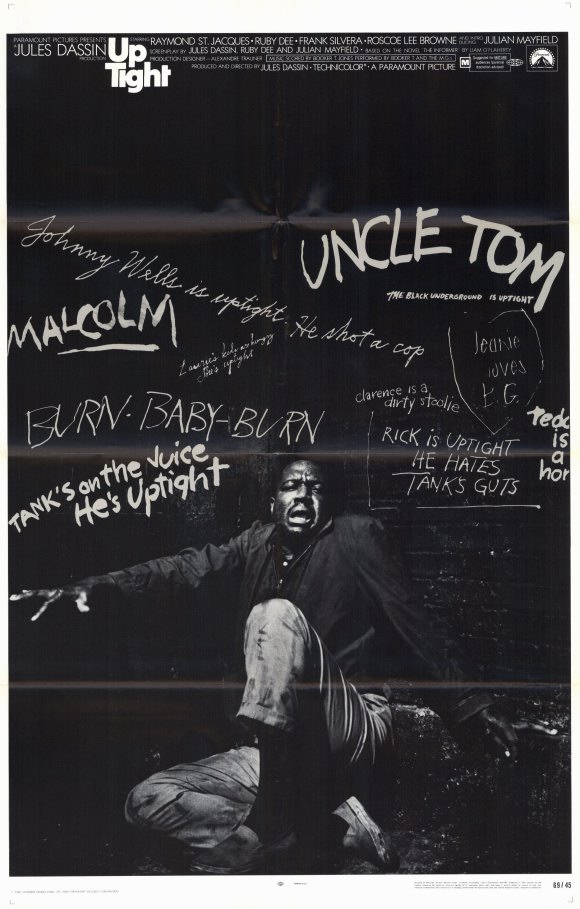

MacLachlan made her feature film debut in “Up Tight” (1968), a remake of John Ford’s “The Informer” with the Irish Republican Army’s struggle against the British replaced by a faction of the black power movement in a Cleveland ghetto. This politically charged, controversial film was released shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. (it begins with documentary footage of King’s funeral procession) and depicted the struggle between groups advocating nonviolent and armed resistance. It was the first American-made film by director Jules Dassin since his blacklisting and exile in Europe, and its cast was a virtual who’s-who of black Hollywood in the late 1960s, including Ruby Dee, Roscoe Lee Browne, Frank Silvera, Max Julien, and Raymond St. Jacques. MacLachlan played Jeannie, girlfriend of the leader of a militant gang (St. Jacques).

Dick Anthony Williams (actor, “Up Tight”): “She was a great teacher and a solid, grounded actress. We had great, great respect for each other. We’d been in a number of things together: “Up Tight,” “The Sophisticated Gents” and other things. She quietly went about her work; she didn’t go for a great deal of fanfare like some actors. She was a very fine actress and fine person, and she’ll be terribly missed.”

Although MacLachlan was not always outspoken about her political beliefs, she did not hesitate to express her views on the status of African-Americans in Hollywood. In a 1968 interview with Soul magazine, she said, “There really hasn’t been, say on television, a truthful honest Black character on any show in a continuing role … 99 percent of the writers are white. And they don’t really know. So what they are doing is writing white roles for black people. The only way to correct that is to have Black writers.”

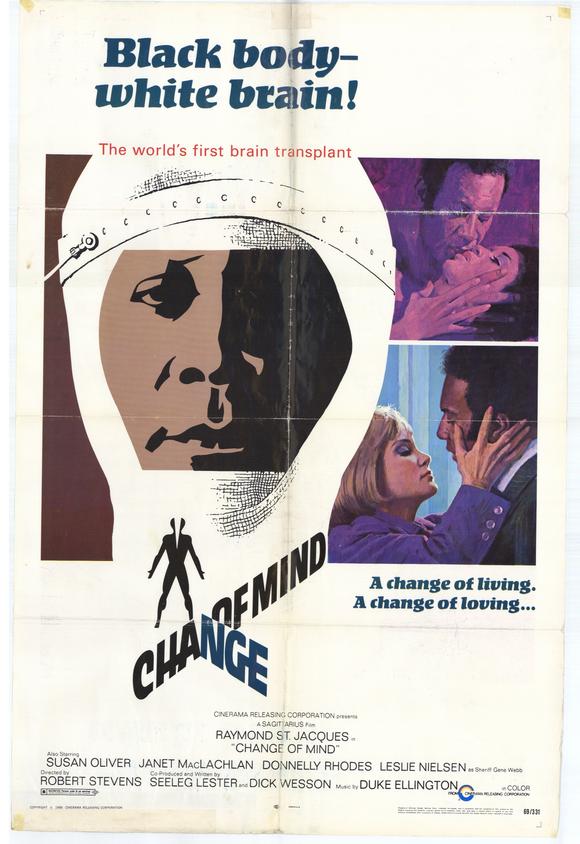

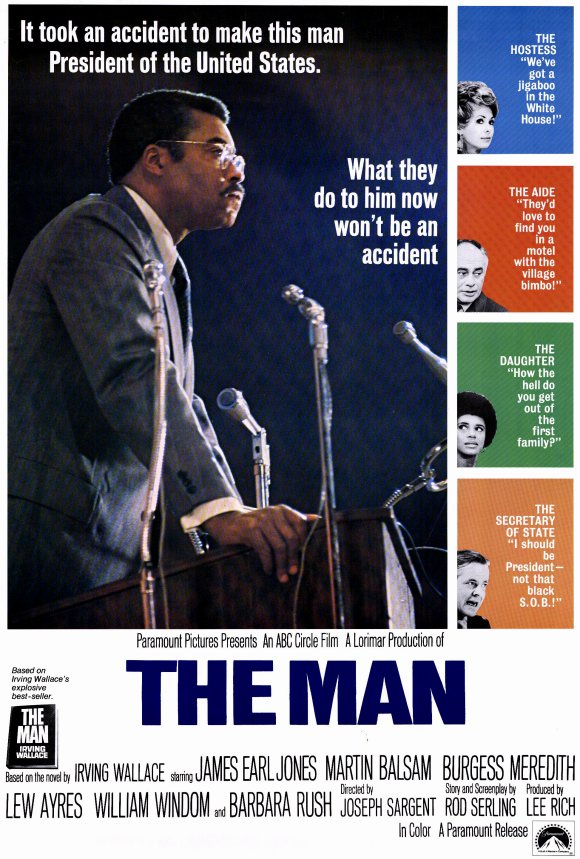

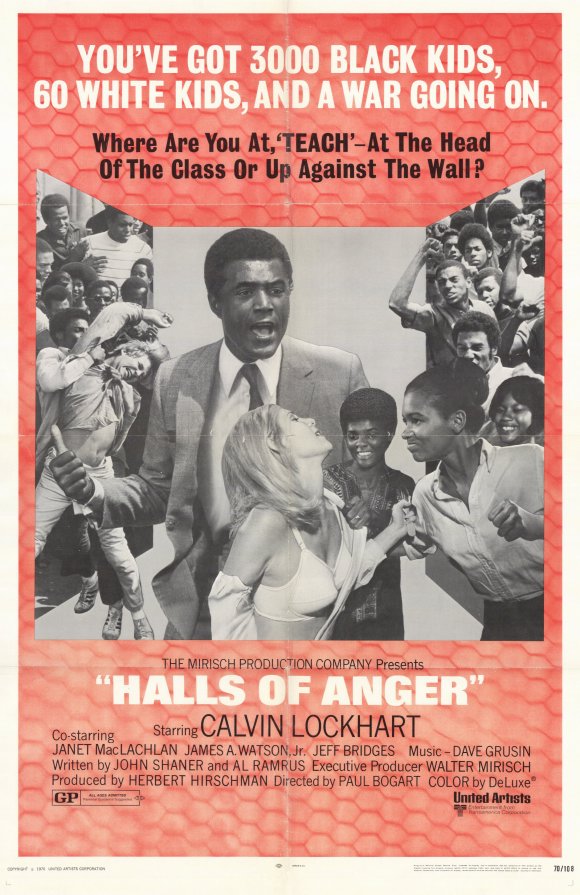

During the early 1970s, MacLachlan avoided the Blaxploitation pictures that were in fashion and instead focused on film roles reflecting her desire to bring credible African-American characters to the screen. In “Change of Mind” (1969), a bizarre sci-fi-drama wherein a white man’s brain is transplanted into a black man’s skull, she played the dead black man’s confused and conflicted widow. In “Halls of Anger” (1970) she was Lorraine Nash, a no-nonsense high school teacher who counsels a fellow educator (Calvin Lockhart) whose classroom is a tempest of racial tensions. “…tick… tick… tick…” (1970) had MacLachlan playing a rather thankless role as the wife of a black sheriff (Jim Brown) in a small, racially divided southern town. “The Man” (1972), based on an Irving Wallace novel and scripted by Rod Serling, cast MacLachlan as the rebellious daughter of the first African-American president of the United States, played by James Earl Jones.

Paul Bogart (director, “Halls of Anger”): “She was a serious actress, and she didn’t have a lot of attitude, which was easy for black actors at that time to have. She was devoted to her craft. All I know is that I liked her a lot, and I depended on her and I was grateful when I had her.”

Contributor: Steve Ryfle

The Movie Posters featured in this article are from the archives of The Museum of UnCut Funk.