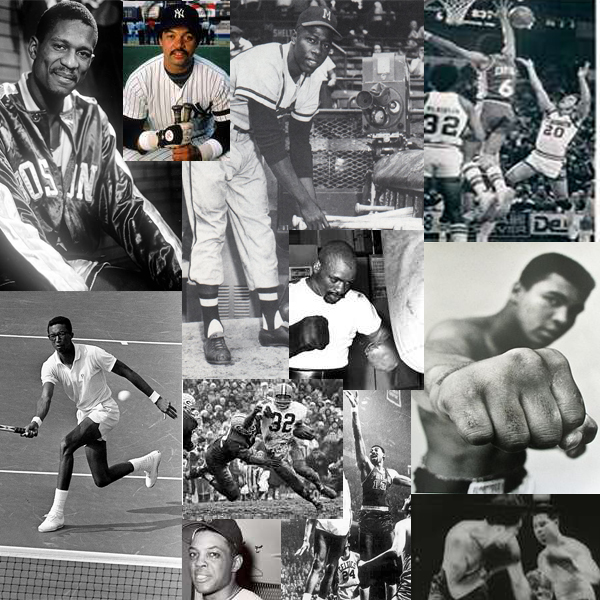

The Museum of UnCut Funk celebrates and pays homage to a few of our favorite Black sports heroes who rocked the 1960’s and the 1970’s (“The Greatest Decade Ever”).

Jim Brown was born on February 17, 1936, in St. Simons, Georgia. He was an outstanding professional football player who led the National Football League in rushing for eight of his nine seasons. He was the dominant player of his era and one of the small number of running backs rated as the best of all time.

In high school and at Syracuse University in New York, Brown displayed exceptional all-around athletic ability, excelling in basketball, baseball, track, and lacrosse as well as football. In his final year at Syracuse, Brown earned All-America honours in both football and lacrosse. Many considered Brown’s best sport to be lacrosse, and he was inducted into both the Pro Football Hall of Fame and the U.S. Lacrosse National Hall of Fame.

From 1957 through 1965, Brown played for the Cleveland Browns of the NFL, and he led the league in rushing yardage every year except 1962. Standing 6.2 feet and weighing 232 pounds, Brown was a bruising runner who possessed the speed to outrun opponents as well as the strength to run over them. He rushed for more than 1,000 yards in seven seasons and established NFL single-season records by rushing for 1,527 yards in 1958 (12-game schedule) and 1,863 yards in 1963 (14-game schedule), a record broken by O.J. Simpson in 1973. On November 24, 1957, he set an NFL record by rushing for 237 yards in a single game, and he equaled that total on November 19, 1961. At the close of his career, he had scored 126 touchdowns, 106 by rushing, had gained a record 12,312 yards in 2,359 rushing attempts for an average of 5.22 yards, and had a record combined yardage (rushing along with pass receptions) of 15,459 yards. Brown’s rushing and combined yardage records stood until 1984, when both were surpassed by Walter Payton of the Chicago Bears.

At 30 years of age and seemingly at the height of his athletic abilities, Brown retired from football to pursue a career in motion pictures. He appeared in many action and adventure films, such as Slaughter (1972) and Slaughter’s Big Rip Off (1973). Brown was also active in issues facing Blacks, forming groups to assist black-owned businesses and to rehabilitate gang members.

[line-sep]

Julius Erving was born on February 22, 1950, in Roosevelt, New York. Erving—called as “Dr. J” by his fans—became known for his style and grace on and off the court during his sixteen-year professional basketball career. A solid player in high school, Erving went on to play for the University of Massachusetts in 1968. At the university, he played on the school’s varsity team for two seasons, averaging more than 26 points and 20 rebounds per game.

Erving left college in 1971 to play for the Virginia Squires, a team in the American Basketball Association (ABA). With the Squires, he scored more than 27 points per game in his first season. But it was the move to the New York Nets in 1973 that allowed Erving to really shine. He helped the team win ABA championships in 1974 and 1976 and received the league’s Most Valuable Player award for each of those seasons. He earned a lot of fans and attracted a lot of attention for his athletic performance—graceful spins, dramatic jump shots, and powerful slam dunks. He was considered by many to be one of the league’s leading players.

In 1976, Erving switched leagues, moving to the National Basketball Association (NBA) to play for the Philadelphia 76ers. In his eleven seasons with the team, he helped them win the 1983 NBA championship. Erving was also selected as the league’s Most Valuable Player in 1981 and played in 11 NBA All-Star games. At the time of his retirement in 1987, he had played in more than 800 games, scoring an average of 22 points per game in the NBA. His career scoring total was more than 30,000 points during ABA and NBA careers.

Erving may have retired, but he hasn’t really left the game. He has worked as a sports analyst for the NBC television network and as an executive for the Orlando Magic, a Florida-based NBA team. He has also pursued many other business opportunities.

[line-sep]

Henry Louis Aaron was born on February 5, 1934 in Mobile, Alabama. Formerly baseball’s all-time home-run king, Aaron played 23 years as an outfielder for the Milwaukee (later Atlanta) Braves and Milwaukee Brewers (1954–76). He holds many of baseball’s most distinguished records, including runs batted in (2,297), extra base hits (1,477), total bases (6,856) and most years with 30 or more home runs (15). He is also in the top five for career hits and runs. Aaron also had the record for most career home runs (755) until Barry Bonds broke it with his 756th home run on August 7, 2007, in San Francisco.

Born in a poor black section of Mobile called “Down The Bay,” Aaron and his family moved to the middle class Toulminville neighborhood when he was a young boy. When he got to high school, Aaron played shortstop and third base on his school’s team. Aaron, perhaps sensing he had a bigger future ahead of him, quit school in 1951 to play in the Negro Leagues for the Indianapolis Clowns.

It wasn’t a long stay. After leading his club to victory in the league’s 1952 World Series, Aaron was recruited the following June to the Milwaukee Braves for $10,000. The Braves assigned their new player to one of their farm clubs, The Eau Claire Bears. Again Aaron did not disappoint, getting named Northern League Rookie of the Year.

A year later, the 20-year-old Hank Aaron got his Major League start when a spring training injury to a Braves outfielder created a roster spot for him. Following a respectable first year (he hit .280), Aaron charged through the 1955 season with a blend of power (27 home runs), run production (106 runs batted in), and average (.328) that would come to define his long career. In 1956, after winning the first of two of his batting titles, Aaron registered an unrivaled 1957 season, taking home the National League MVP and nearly nabbing the Triple Crown by hitting 44 homeruns, knocking in another 132, and batting .322.

That same year, Aaron demonstrated his ability to come up big when it counted most. His 11th inning homerun in late September propelled the Braves to the World Series, where he led underdog Milwaukee to an upset win over the New York Yankees in seven games.

With the game still years away from the multi-million dollar contracts that would later dominate player salaries, Aaron’s annual pay in 1959 was around $30,000. When he equaled that amount that same year in endorsements, Aaron realized there may be more in store for him if he continued to hit for power. “I noticed that they never had a show called ‘Singles Derby,'” he said.

He was right, of course, and over the next decade and a half, the always-fit Aaron banged out a steady stream of 30 and 40 homerun seasons. In 1973, at the age of 39, Aaron was still a force, clubbing a remarkable 40 homeruns to finish just one run behind Babe Ruth’s all-time career mark of 714.

But the chase to beat the Babe’s record revealed that world of baseball was far from being free of the racial tensions that prevailed around it. Letters poured into the Braves offices, as many as 3,000 a day for Aaron. Some wrote to congratulate him, but many others were appalled that a Black man should break baseball’s most sacred record. Death threats were a part of the mix.

Still, Aaron pushed forward. He didn’t try to inflame the atmosphere, but he didn’t keep his mouth shut either, speaking out against the league’s lack of ownership and management opportunities for minorities. “On the field, Blacks have been able to be super giants,” he said. “But, once our playing days are over, this is the end of it and we go back to the back of the bus again.”

In 1974, after tying the Babe on Opening Day in Cincinnati, Aaron came home with his team. On April 15, he banged out his record 715th homerun at 9:07 P.M. in the fourth inning against the Los Angeles Dodgers. It was a triumph and a relief. The more than 50,000 fans on hand cheered him on as he rounded the bases. There were fireworks and a band, and when he crossed home plate, Aaron’s parents were there to greet him.

Overall, Aaron finished the 1974 season with 20 homeruns. He played two more years, moving back to Milwaukee to finish out his career to play in the same city where he’d started.

After retiring as a player, Aaron moved into the Atlanta Braves front office as executive vice-president, where he has been a leading spokesman for minority hiring in baseball. He was elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1982. His autobiography, I Had a Hammer, was published in 1990.

In 1999, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of breaking Ruth’s record, Major League Baseball announced the Hank Aaron Award, given annually to the best overall hitter in each league. Hank Aaron was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002.

[line-sep]

Boxer, philanthropist, social activist Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr. was born on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky. Once one of the top American boxers, Muhammad Ali has shown that he is not afraid of any fight—inside or outside the ring. Growing up in the segregated South, Ali experienced firsthand the prejudice and discrimination that Blacks faced during this era. At the age of 12, Ali discovered his talent for boxing through an odd twist of fate. His bike was stolen, and Ali told a police officer, Joe Martin, that he wanted to beat up the thief. “Well, you better learn how to fight before you start challenging people,” Martin reportedly told him at the time. In addition to being a police officer, Martin also trained young boxers at a local gym.

Ali started working with Martin to learn how to box, and soon began his boxing career. In his first amateur bout in 1954, he won the fight by split decision. Ali went on to win the 1956 Golden Gloves Championship for novices in the light heavyweight class. Three years later, he won the Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions and the Amateur Athletic Union’s national title for the light-heavyweight division.

In 1960, Ali won a spot on the U.S. Olympic Boxing Team. He traveled to Rome, Italy, to compete. At 6 feet 3 inches tall, Ali was an imposing figure in the ring. He was known for his footwork, and for possessing a powerful jab. After winning his first three bouts, Ali then defeated Zbigniew Pietrzkowski from Poland to win the gold medal.

After his Olympic victory, Ali was heralded as an American hero. He soon turned professional with the backing of the Louisville Sponsoring Group. During the 1960s Ali seemed unstoppable, winning all of his bouts with majority of them being by knockouts. He took out British heavyweight champion Henry Cooper in 1963 and then knocked out Sonny Liston in 1964 to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

Often referring to himself as “the greatest,” Ali was not afraid to sing his own praises. He was known for boasting about his skills before a fight and for his colorful descriptions and phrases. In one of his more famously quoted descriptions, Ali told reporters that he could “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” in the boxing ring.

This bold public persona belied what was happening in Ali’s personal life, however. He was doing some spiritual searching and decided to join the black Muslim group, the Nation of Islam, in 1964. At first he called himself Cassius X, but then settled into the name Muhammad Ali. Two years later, Ali started a different kind of fight when he refused to acknowledge his military service after being drafted. He said that he was a practicing Muslim minister, and that his religious beliefs prevented him from fighting in the Vietnam War.

In 1967, Ali put his personal values ahead of his career. The U.S. Department of Justice pursued a legal case against Ali, denying his claim for conscientious objector status. He was found guilty of refusing to be inducted into the military, but Ali later cleared his name after a lengthy court battle. Professionally, however, Ali did not fare as well. The boxing association took away his title and suspended him from the sport for three and a half years.

Returning to the ring in 1970, Ali won his first bout after his forced hiatus. He knocked out Jerry Quarry in October in Atlanta. The following year, Ali took on Joe Frazier in what has been called the “Fight of the Century.” Frazier and Ali went for 15 rounds before Frazier dropped Ali to the ground, scoring a knockout. Ali later beat Frazier in a 1974 rematch.

Another legendary Ali fight took place in 1974. Billed as the “Rumble in the Jungle,” the bout was organized by promoter Don King and held in Kinshasa, Zaire. Ali fought the reigning heavyweight champion George Foreman. For once, Ali was seen as the underdog to his younger, powerful opponent. Ali silenced his critics by defeating Foreman and once again becoming the heavyweight champion of the world.

Perhaps one of his toughest bouts took place in 1975 when he battled longtime rival Joe Frazier in the “Thrilla in Manila” fight. Held in Quezon City, Philippines, the match lasted for more than 14 rounds with each fighter giving it their all. Ali emerged victorious in the end.

By the late 1970s, Ali’s career had started to decline. He was defeated by Leon Spinks in 1978 and was knocked out by Larry Holmes in 1980. In 1981, Ali fought his last bout, losing his heavyweight title to Trevor Berbick. He announced his retirement from boxing the next day.

In his retirement, Ali has devoted much of his time to philanthropy. He announced that he has Parkinson’s disease in 1984, a degenerative neurological condition, and has been involved in raising funds for the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center in Phoenix, Arizona. Over the years, Ali has also supported the Special Olympics and the Make a Wish Foundation among other organizations.

Muhammad Ali has traveled to numerous countries, including Mexico and Morocco, to help out those in need. In 1998, he was chosen to be a United Nations Messenger of Peace because of his work in developing countries.

In 2005, Ali received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush. He also opened the Muhammad Ali Center in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, that same year. “I am an ordinary man who worked hard to develop the talent I was given,” he said. “I believed in myself and I believe in the goodness of others,” said Ali. “Many fans wanted to build a museum to acknowledge my achievements. I wanted more than a building to house my memorabilia. I wanted a place that would inspire people to be the best that they could be at whatever they chose to do, and to encourage them to be respectful of one another.”

Despite the progression of his disease, Ali remains active in public life. He embodies the true meaning of a champion with his tireless dedication to the causes he believes in. He was on hand to celebrate the inauguration of the first African-American president in January 2009 when Barack Obama was sworn-in. Soon after the inauguration, Ali received the President’s Award from the NAACP for his public service efforts.

As he has done every year since its inception, Ali hosted the 15th Annual Celebrity Fight Night Awards in Phoenix in March 2009. The event benefited the Celebrity Fight Night Foundation and the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center.

Ali has been married to his fourth wife, Yolanda, since 1986. The couple has one son, Asaad, and Ali has several children from previous relationships, including daughter Laila who followed in his footsteps for a time as a professional boxer.

[line-sep]

Arthur Robert Ashe, Jr. was born on July 10,1943, in Richmond, Virginia. The oldest of Arthur Ashe, Sr. and Mattie Cunningham’s two sons, Arthur Ashe, Jr. blended finesse and power to forge a groundbreaking tennis game. He became the first, and currently only, African-American to win the men’s singles at Wimbledon, the U.S. Open, or the Australian Open.

Ashe’s childhood was marked by hardship and opportunity. Under his mother’s direction, Ashe was reading by the age of four. But his life was turned upside-down two years later, when Mattie passed away.

Ashe’s father, fearful of seeing his boys fall into trouble without their mother’s discipline, began running a tighter ship at home. Ashe and his younger brother Johnnie went to church every Sunday, and after school were required to come straight home. Arthur, Sr. even clocked the distance: “My father…kept me home, out of trouble. I had exactly 12 minutes to get home from school, and I kept to that rule through high school.”

About a year after his mother’s death, Arthur discovered the game of tennis, picking up a racket for the first time at the age of seven, at a park not far from his home. Sticking with the game, Ashe eventually caught the attention of Dr. Robert Walter Johnson, Jr., a tennis coach from Lynchburg, Virginia, who was active in the black tennis community. Under Johnson’s direction, Ashe excelled.

In his first tournament, Ashe reached the junior national championships. Driven to excel, he eventually moved to St. Louis to work closely with another coach, winning the junior national title in 1960 and again in 1961. Ranked the fifth best junior player in the country, Ashe accepted a scholarship at UCLA, where he graduated with a degree in business administration.

Ashe continued to refine his game, gaining the attention of his tennis idol, Pancho Gonzales, who further helped Ashe hone his serve-and-volley attack. The training all came together in 1968, when the still-amateur Ashe shocked the world by capturing the U.S. Open title. Two years later, he took home the Australian title, and in 1975 registered another upset by beating Jimmy Connors in the Wimbledon finals.

For Ashe, however, success also brought opportunity and responsibility. He didn’t relish his status as the sole Black star in a game dominated by white players, but he didn’t run away from it either. With his unique pulpit, he pushed to create inner city tennis programs for youth; helped found the Association of Men’s Tennis Professionals; and spoke out against apartheid in South Africa—even going so far as to successfully lobby for a visa so he could visit and play tennis there.

Ashe’s causes were shaped by both his own personal story and his health. In 1979, he retired from competition after suffering a heart attack, and wrote a history of African-American athletes: A Hard Road to Glory (3 vols, 1988). He also served as national campaign chairman of the American Heart Association.

Ashe was plagued with health issues over the last 14 years of his life. After undergoing a quadruple bypass operation in 1979, he went under the knife again in 1983 for a second bypass. In 1988, he underwent emergency brain surgery after experiencing paralysis of his right arm. A biopsy taken during a hospital stay revealed that Ashe had AIDS. Doctors soon figured out that Ashe had become positive for H.I.V., the virus that causes AIDS, from a transfusion of bad blood during his second heart operation.

Initially, Ashe kept the news hidden from the public. But in 1992, Ashe came forward with the news after he learned that USA Today was working on a story about his health battle. Finally free from the burden of trying to hide his condition, Ashe poured himself into the work of raising awareness about the disease. He delivered a speech at the United Nations, started a new foundation, and laid the groundwork for a $5 million fundraising campaign for the institution.

He continued to work, even as his health began to deteriorate, making it down to Washington D.C. in late 1992 to participate in a protest over the U.S. treatment of Haitian refugees. For his part in the demonstration, Ashe was taken away in handcuffs. It was a poignant final display for a man who was never shy about showing his concern for the welfare of others.

On February 6, 1993, Arthur Ashe passed away. Four days later he was laid to rest in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. Some 6,000 people attended the service. Ashe, who was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1985, was married to Jeanne Moutoussamy from 1977 until his death. They have one daughter, Camera.

[line-sep]

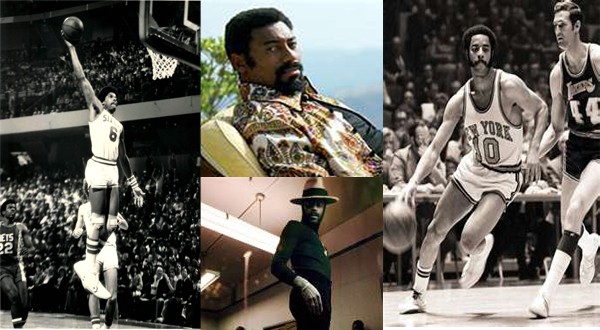

Born on August 21, 1936, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and known as “Wilt the Stilt” and the “Big Dipper,” Wilt Chamberlain was one of the greatest basketball players of all time. He scored more than 30,000 points during his professional career.

Chamberlain was a standout player at Overbrook High School in Philadelphia. He played on the school’s varsity team for three years, scoring more than 2,200 points in total. Standing at 6-feet 11-inches, Chamberlain physically dominated other players. He eventually reached his full height of a staggering 7-feet 1-inch tall. Many of his nicknames were derived from his stature. He hated being called “the Stilt,” which came from a local reporter covering high school athletics. But Chamberlain didn’t mind “Dipper” or “Big Dipper,” a nickname given to him by friends because he had to duck his head down when passing through a doorframe.

When it came time for college, Chamberlain was sought after by many top college basketball teams. He chose to go to the University of Kansas, making his college basketball debut on the Jayhawks in 1956. Chamberlain helped the team make it to the NCAA finals in 1957. The Jayhawks were defeated by North Carolina, but Chamberlain was chosen as the Most Outstanding Player of the tournament. Continuing to excel, he made the all-America and all-conference teams the following season.

Leaving college in 1958, Chamberlain had to wait a year before going professional due to NBA rules. He chose to spend the next season performing with the Harlem Globetrotters before landing a spot on the Philadelphia Warriors. In 1959, Chamberlain played his first professional game in New York City against the Knicks, scoring 43 points. His impressive debut season netted him several prestigious honors, including NBA Rookie of the Year and NBA Most Valuable Player. Also during this season, Chamberlain began his rivalry with Celtics defensive star Bill Russell. The two were fierce competitors on the court, but they developed a friendship away from the game.

Chamberlain’s most famous season, however, came in 1962. That March, he scored his first 100-point game. By season’s end, Chamberlain racked up more than 4,000 points, becoming the first NBA player to do so, scoring an average of 50.4 points per game. At the top of his game, Chamberlain was selected for the All-NBA first team for three years in a row—1960, 1961, and 1962.

Chamberlain stayed with the Warriors as they moved out to San Francisco in 1962. He continued to play well, averaging more than 44 points per game for the 1962-1963 season and almost 37 points per game for the 1963-1964 season. Returning to his hometown in 1965, Chamberlain joined the Philadelphia 76ers. There he helped his team score an NBA championship win over his former team. Along the way to the championship, he also assisted the Sixers in defeating the Boston Celtics in the Eastern Division Finals. The Celtics were knocked out of the running after eight consecutive championship wins. Crowds gathered to watch the latest match between two top center players: Chamberlain and Bill Russell.

Traded to the Los Angeles Lakers in 1968, Chamberlain again proved that he was a competitive, successful athlete. He helped the Lakers win the 1972 NBA championship, triumphing over the New York Knicks in five straight games, and was named the NBA Finals MVP.

By the time he retired in 1973, Chamberlain had amassed an amazing array of career statistics. He played in 1,045 games, and achieved an average of 30.1 points per game. This average was the NBA record until Michael Jordan broke it when he retired in 1998. To this day, Chamberlain still holds the record for the highest number of points scored in a single game, and remains notable for never fouling out of an NBA game.

After his retirement, Chamberlain explored other opportunities. He published his autobiography, Wilt: Just Like Any Other 7-Foot Black Millionaire Who Lives Next Door in 1973. He tried coaching for a time, and was a popular pitchman for commercials. Chamberlain later branched out in acting, appearing in the 1984 action film Conan the Destroyer with Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Still, his feats as a player were not forgotten. In 1978, Chamberlain was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame. He was named one of the top all-time 50 NBA players in 1996. In 1991, Chamberlain claimed another, more unusual distinction, when he wrote in his book A View from Above that he had slept with more than 20,000 women during his lifetime.

Chamberlain died of heart failure on October 12, 1999, at his Los Angeles home. He once said that “no one cheered for Goliath,” but the response to his passing proved that to be false. “Wilt was one of the greatest ever, and we will never see another like him,” said basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. His former rival Bill Russell told the press that “he and I will be friends through eternity.”

Source: IMDB, History Channel, A&E, ESPN and Wikipedia

![ali_muhammad_130x171[getty] ali_muhammad_130x171[getty]](http://www.museumofuncutfunk.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/ali_muhammad_130x171getty.jpg)