I had an opportunity to meet Billy Dee Williams at Comic Con in Philly and take a picture with him. He was a extremely approachable and when I mentioned the Museum of UnCut Funk he expressed an interest in our project and wanted to know more about what we were doing.

Billy Dee Williams was born William December Williams, April 6, 1937, in New York, NY; son of December and Loretta Williams. He has been married three times. He and his third wife Teruko have three children: Corey, Miyako, Hanako. Billy attended the High School of Music and Art and National Academy School of Fine Arts in New York City.

Billy has had both a stage and film presence. On stage he appeared in Firebrand of Florence (1945), The Cool World (1966), A Taste of Honey (1961), I Have a Dream (1976) and Fences, (1988).

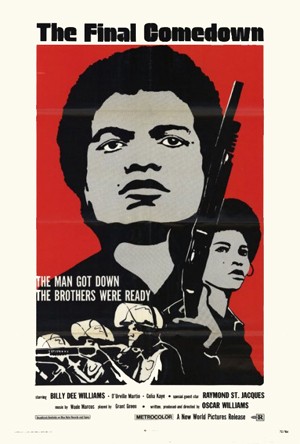

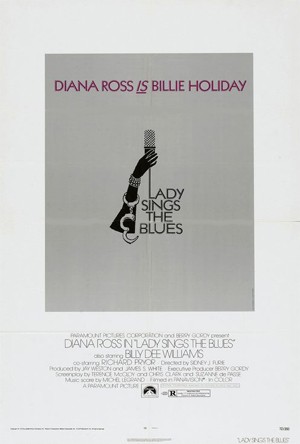

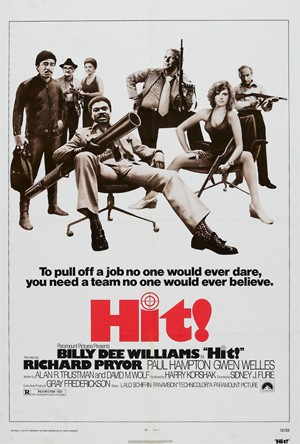

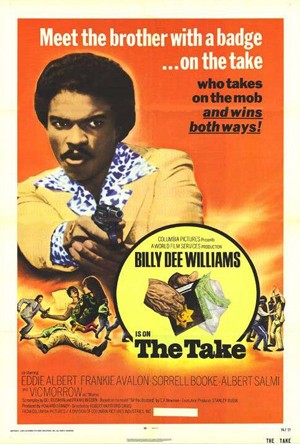

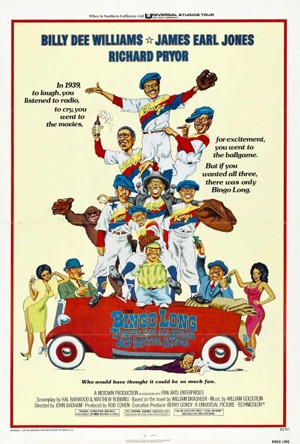

As for film, his credits include: The Last Angry Man (1959); The Out-of-Towners (1970); The Final Comedown (1972); Lady Sings the Blues (1972); Hit! (1972); The Take (1974); Mahogany (1976); The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings (1976); The Empire Strikes Back (1980); Nighthawks (1981); Return of the Jedi (1983); Marvin & Tige (1984).

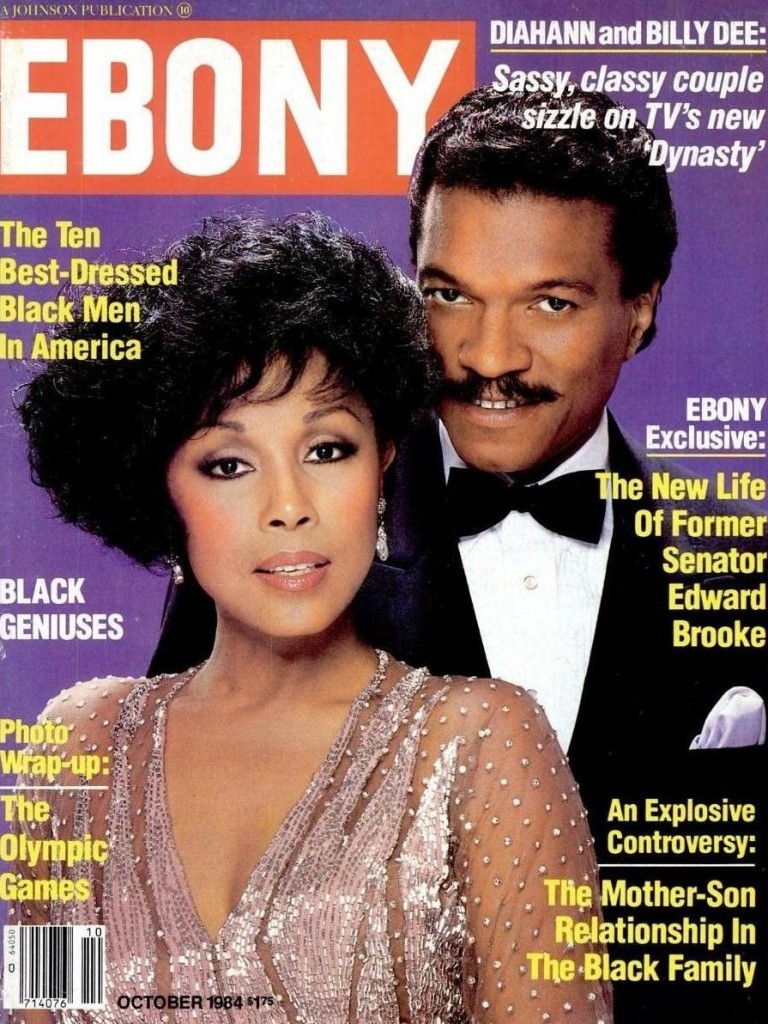

His television appearances include: Dynasty (1980s) and the films Brian’s Song (1971); The Scott Joplin Story (1976); The Jacksons: An American Dream (1992); Marked for Murder (1993) and Percy and Thunder (1993). He is also an artist. An exhibition of his paintings, The Art of Billy Dee Williams, was displayed at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in 1993. Several film and stages appearances have followed.

These movie posters are from the collection of The Museum of UnCut Funk

Broke Through in Brian’s Song

By his early twenties Williams was working regularly in the theater, first making a splash in A Taste of Honey. He studied acting with, among others, Sidney Poitier. “When I met him he gave me a sense of hope by just watching him moving in a certain kind of way,” the younger actor told Ebony. “That certainly gave me the feeling that I’ve got something to offer, that there is a place for me.” He took some film work, including roles in The Last Angry Man and The Out-of-Towners, but soon realized that stardom wasn’t around the corner.

After an abortive attempt at a singing career, Williams traveled to Europe, returning to the United States in 1970. The following year he earned the role of football star Gale Sayers in Brian’s Song, an Emmy Award-winning television film costarring James Caan. That tale of friendship and tragedy established Williams’s credentials as a dramatic actor; a year later he would emerge as a leading man.

Music business legend Berry Gordy, who had branched into film with his Motown pictures company, was sufficiently impressed by Williams’s performance to offer him a critical role in Lady Sings the Blues, with singing superstar Diana Ross in the lead. The actor initially was disinclined to take the part since he regarded it as insufficiently serious and doubted Ross’s ability as an actress.

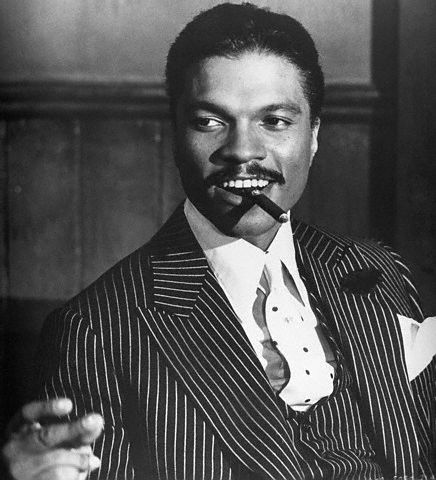

Ultimately accepting the part, Williams played Louis McKay, who becomes involved with ill-fated jazz singer Billie Holiday. Ross earned an Academy Award for her portrayal of Holiday, while Williams’s role in the film was a milestone in that it glamorized black men in a new way. “His hair and neatly trimmed moustache glisten,” wrote Hollie I. West of the Los Angeles Times. “His smile is easy and warm. He is immaculately dressed in a business suit and he has a coat draped over his shoulders.” As the actor’s manager, Shelly Berger, explained to Mademoiselle’s Bernikow, “In that shot, he went from Billy Dee Williams, character actor, to Billy Dee Williams, matinee idol. All of a sudden he became ‘the black Cląrk Gable.’”

Williams’s suave, sexual manner—emblematized by what the Los Angeles Herald Examiner’s Jones called his “devastating smile”—was a novel model of African American male sexuality on the big screen in the era of blaxploitation film tough guys. Thus he was given the “black Clark Gable” label, which likened him to the star of Gone With the Wind but reproached him with the strictures of race-conscious casting. In particular, the actor expressed frustration with the Hollywood taboo against love scenes between black men and white women. “It makes me very sad,” he told Bernikow. “Very frustrated. It makes me very angry.” In 1976 he appeared opposite Ross again in Mahogany, portraying a grass-roots political activist whose lover is swept up by the fashion world.

Spiritual Intervention Led to King Role

Williams returned to the stage to play Martin Luther King, Jr., in the 1976 Broadway production Have a Dream. The actor revealed to Judy Klemesrud of the New York Times that he had rejected the lead in a film biography of King two years earlier but ultimately accepted the stage role because he felt otherworldly forces demanded it. “I went to an Armenian lady in California who reads tarot cards and coffee grounds. She said,“I keep seeing this thing you’re going to do, a religious leader leading thousands of people.’ She told me the same thing when I went back six months later.” Berger then brought him the playscript “and said I had to do it, and he’s really all big bucks and very cynical. That, to me, was some sort of sign.”

Williams’s faith in all manner of divination has been a constant; “Actually, I believe in everything, including astrology and tarot cards. All of it is just another way for people to try and tighten the link to the spirits in our universe. I believe it exists for all people.” The spirit of King, he felt, inhabited him onstage. Rather than study the minister-activist’s mannerisms, he claimed to Klemesrud, “I would just allow it to happen. I mean, I would immerse myself enough in him so that I just fell into him. I just let it happen naturally.” Los Angeles Times reviewer William Glover reported that the actor did “excellently well” in the role.

Williams went on to portray Scott Joplin—the composer-pianist whose work brought ragtime music prominence and who achieved posthumous fame with the hit movie The Sting for his 1902 composition “The Entertainer”—in a biopic for NBC television. “He was really extraordinary, had a lot of depth,” the actor said of Joplin in Soul. “He took ragtime out of a rural setting and made it classical.”

Williams’s popularity by this point had reached a new high; as he told West of the Los Angeles Times, “I see this image-making as an opportunity to communicate with blacks and whites, especially children. The way I looked at Alan Ladd, Humphrey Bogart, or those other great heroes on the screen when I was a kid, I feel that if I’m to be a catalyst, I have to draw the attention of all people.” His next high-profile film role came with the 1976 release The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings, a comedy-drama about veterans of baseball’s negro leagues. He described his character, Bingo Long—based on pitching marvel Satchel Paige—to Soul’s Jeanne Allyson Fox as a “ridiculous optimist.”

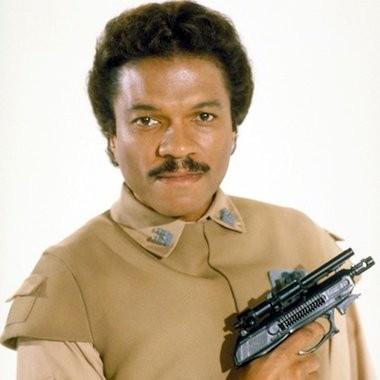

Tackled Colorblind Part in Star Wars Films

Williams worked steadily in films, taking supporting parts in mainstream fare like the 1981 Sylvester Stallone action movie Nighthawks, but his major role during this period came when he was cast as intergalactic entrepreneur and rogue Lando Calrissian in The Empire Strikes Back, the second—and many argue the finest—of the phenomenally successful Star Wars films. Calrissian plays a crucial role in the development of the action, and though he betrays the heroes early in the film to protect his own interests, he is later instrumental in their triumph.

Williams was particularly pleased with the role because the character had no “race” in the script except human; at last, some purely colorblind casting had come his way. Williams described the character inEbony: “He’s a person of the universe.” In a similar vein, he remarked to the Los Angeles Herald Examiner’s Jones, “I was very happy with my character. The only thing that said Lando Calrissian was ethnic was his looks.” In 1983 he reprised the role in the final film of the series, Return of the Jedi.

In 1984 Williams joined the cast of the prime-time television soap opera Dynasty, depicting record industry magnate Brady Lloyd. At the same time, he expressed a desire to take on more ambitious characterizations; he told Jones that he would like to play former U.S. President Richard Nixon. He returned to the stage in the 1988 Broadway production of award-winning playwright August Wilson’s Fences, though the role in the film version went to James Earl Jones.

During the 1980s Williams met controversy, the result of his television commercials for Colt 45 malt liquor; numerous voices in the black community—from religious leaders to rappers—attacked the aggressive hawking of alcohol to black audiences by Blacks they felt had been co-opted by the liquor industry. Williams responded defensively, dismissing his critics and accusing them of overreacting.

In 1989 Williams appeared in another blockbuster, playing Gotham City district attorney Harvey Dent in Tim Burton’s Batman. The actor claimed to have modeled his character on controversial Black politician Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. “I did Batman because it sounded like a lot of fun,” Williams told Barry Koltnow of the Orange County Register, “and they created the character just for me. It’s an American institution and was impossible to pass up.” In fact, the actor has avoided taking parts for the money alone because, he claims, such a tendency “can destroy your career.”

During the late 1980s Williams also began laboring from the early evening until dawn every night to prepare a large number of paintings for an exhibition of his work. “People talk about painting being therapy, and I guess they’re right,” he noted to Koltnow. “I need to paint. I find it mellows me out. My wife can’t even get me into an argument anymore when I’m painting.”

His marriage to the wife in question—his third, Teruko—ended a few years later, more than 20 years after it had begun. People reported that the couple “blames that standby, irreconcilable differences, for the split.” “I think I’m a good father,” Williams had insisted to the Herald Examiner nearly a decade earlier, adding, “As a parent, you have the responsibility to create a foundation for your children so that they can meet all the challenges.”

Williams continued to work steadily into the 1990s, appearing in the television films The Jacksons: An American Dream —in which he portrayed Berry Gordy—as well as Marked for Murder, Percy and Thunder, and other productions. 1993 also marked the opening of an exhibit of his paintings at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City; many of his pieces salute jazz artists and portray the conflicting currents of their lives. “I think of film when I paint,” he told Upscale. “Even the luminosity that I always keep working for is really about film. But my idea is not to paint paintings that will decorate somebody’s house. My idea is to paint paintings so that when you walk into a room I’m pulling you in, or that makes you suddenly stop and wonder: ‘What is this? There is something groovy, something else going on here.’ Also I want to give you what is obvious and what is not obvious to the eye.”

Williams, clearly intending to follow the dictates of his own sensibility, has moved from character actor to glamorous leading man and back again, expressing no interest in being pigeonholed. And ultimately, as he revealed to Soul, his endeavors have become linked to the spiritual: “I am an artist no matter what I do,” he proclaimed. “I live for creativity. I think everyone should. It is the antithesis of being destructive. I want to always be able to see—to walk into any situation and see the people and what is going on.”