Stephen Whitty is a writer for The Star Ledger, the largest newspaper in New Jersey. Stephen has agreed to allow the Museum Of UnCut Funk to reprint a excerpt from his article.

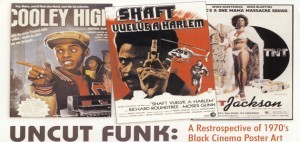

It lasted too long to be a fad, and was probably too much fun to be a movement. It was criticized by its own community from the beginning, and deserted by its audience in the end. But for the first half of the 1970s, genre films made by and for African-Americans — dubbed “blaxploitation” — were a hugely profitable and popular part of American movies.

Today, they’re being nostalgically remembered. A new oral history, “Reflections on Blaxploitation” , collects interviews with more than 20 filmmakers and actors. “Black Hollywood,” a recently rediscovered documentary, looks at it as part of the entire history of Black cinema. But the genre didn’t get much love at the time, from high-minded critics or socially progressive organizations. Perhaps that was because it was too rough, too raw, too rude — particularly in contrast to earlier African-American films. Oscar Micheaux, for example — a pioneering black director who shot some of his movies in Fort Lee — was a serious artist, concerned with issues of class and identity. He was a showman, too — he promoted stars like Paul Robeson and Lorenzo Tucker (“the first Negro leading man in motion pictures”) and had a flair for melodrama — but his films were never crass or crude.

Neither were the movies that followed during the civil rights era. There were musicals like “Carmen Jones” and dramas like “Intruder in the Dust”; new personalities were discovered, from the iconic (Sidney Poitier) to the tragic (Dorothy Dandridge) to the now criminally forgotten (James Edwards.) Yet these were made by white directors, aimed primarily at white audiences. Their hope was to liberalize the majority, not entertain a minority. It took the ’60s — and a rising tide of black power — to create a new kind of film for and by African-Americans. It came slowly. You can see hints of it in 1967’s “In the Heat of the Night” in which a coldly furious Sidney Poitier slaps a white racist. That was an announcement — no longer would the black hero suffer nobly, silently. (The sequel, 1970’s “They Call Me MISTER Tibbs” only confirmed it.) Other films — like that year’s “Cotton Comes to Harlem,” directed by veteran activist Ossie Davis — added layers of cool humor and hip weariness to their black heroes.

It took African-American directors Gordon Parks and Melvin Van Peebles to really kick the movement off, though, the next year — and show two possible paths. Parks’ “Shaft” took the conservative approach. A standard detective film in everything but race, it embraced genre rules rather than upending them, and sought no new artistic breakthroughs (apart from its immediately classic, funky Isaac Hayes score). It aimed to give black audiences the same kind of Hollywood movies that white ones got — a “black James Bond,” is how Parks described Richard Roundtree’s hero.

Van Peebles’ “Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song,” meanwhile, was proudly, provocatively radical — right from the title (which most newspapers refused to print) and its unabashed sex (causing it to be “Rated X — by an all-white jury!” as the posters announced). Financed independently (Bill Cosby loaned the director $50,000), it was a literally revolutionary film, with artsy camera work and prostitutes and Black Panthers as heroes. Parks wanted to be part of the system; Peebles wanted to turn it upside down. But when these very opposite films both became hits, copycats jumped in, mixing elements of both. From Parks, they took a fondness for conventional, crowd-pleasing genres — action pictures, horror films, comedies (while ignoring his studied professionalism). From Van Peebles, they grabbed a rebellious identification with anti-heroes — pimps, drug dealers, thieves (while studiously avoiding the outsider politics behind it.)

And “blaxploitation” began.

Stephen Whitty graduated from New York University’s School of the Arts with a BFA in Film, the school’s fiction prize, and, obviously, few prospects. He has, nonetheless, written screenplays, published short stories, reviewed movies, and done profiles, essays and other articles for more than 30 years, appearing in magazines from Entertainment Weekly to Cosmopolitan.

To read more of Stephen’s article please visit http://www.nj.com/entertainment/tv/index.ssf/2009/07/looking_back_at_blaxploitation.html