The Museum Of UnCut Funk discovered this article by Jane Stucliffe. We have emailed Ms. Stucliffe for an interview but have not heard from her as of yet. We hope you enjoy her essay.

Two thousand people sat with their faces turned to the sky. High above the airfield, a pilot had just finished carving a crisp figure eight in the air. Suddenly, the plane seemed to stumble. Twisting and turning, it began to fall from the sky. The crowd watched in horror. Had something happened to the pilot?

But the woman in the cock- pit of the plane on October 15, 1922, was in perfect control. Only two hundred feet above the ground she straightened out the tumbling aircraft and soared back into the sky. By the time she landed her plane, the crowd was on its feet, roaring with delight. Everyone cheered for Bessie Coleman, the first licensed black pilot in the world.

Growing Up

Bessie Coleman was born on January 26, 1892. She was a bright girl and a star pupil in school. In Waxahachie, Texas, where Bessie grew up, black children and white children 13 attended different schools. Each year Bessie’s school closed for months at a time. Instead of studying, the children joined their parents picking cotton on big plantations. Bessie’s mother was proud of her daughter ’s sharp mind. She didn’t want Bessie to spend her life picking cotton, and urged her to do something special with her life.

Coleman, in uniform, stands on the runner of a Model T Ford. The nose and right wing of her plane are to her left.

Learning to Fly

In 1915, when she was 23, Bessie Coleman moved to Chi- cago. She found a job as a mani- curist in a men’s barbershop. Coleman loved her job and the interesting people she met there. After the United States entered World War I in 1917, soldiers returning from the war often came to the shop. Coleman was fascinated by their stories of daredevil pilots. She read everything she could about airplanes and flying. She later recalled, “All the articles I read I finally convinced me I should be up there flying and not just reading about it.”

Bessie Coleman asked some of Chicago’s pilots for lessons. They refused. No one thought that an African American woman could learn to fIy.

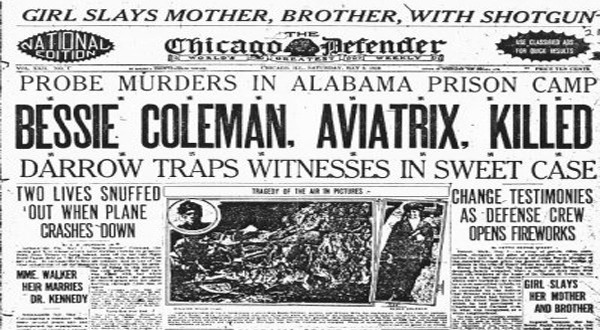

In desperation, Coleman asked Robert Abbott for help. Abbott owned Chicago’s African American newspaper, The Chi- cago Defender. He had often promised to help members of the black community with their problems. Abbott told Coleman to forget about learning to fly in the United States. Go to France, he said to her, where no one would care if her skin was black or white.

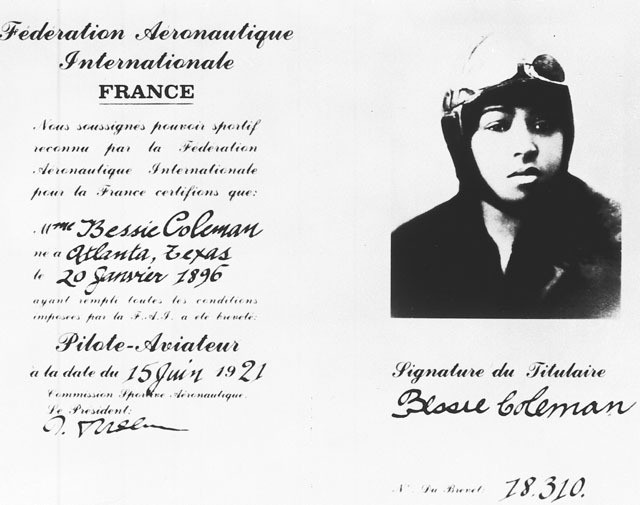

So she did. First Coleman learned to speak French. Then she applied to a French flying school and was accepted. On November 20, 1920, Coleman sailed for France, where she spent the next 3 seven months taking flying lessons. She learned to fly straight and level, and to turn and bank the plane. She practiced making perfect landings. On a second trip to Europe, she spent months mastering rolls, loops, and spins. These were the tricks she would need if she planned to make her living as a performing pilot.

Performing in Airshows

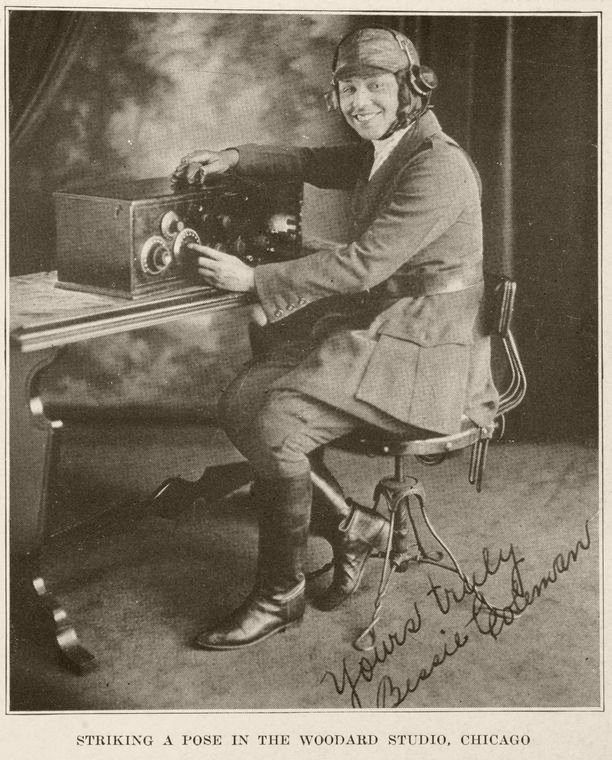

Coleman returned to the United States in the summer of 1922. Wherever she perforrned, other African- Americans wanted to know where they, too, could learn to fly. It was a question that made Coleman sad. She hoped that she could make enough money from her airshows to buy her own plane. Then she could open a school so everyone would have a chance to feel the free- dom she felt in the sky.

By early 1923, Coleman was close to her goal. She had saved her money and bought a plane Then, as she was flying to an airshow in California, her en- gine stalled. The brand-new plane crashed to the ground.

Coleman suffered a broken leg and three broken ribs. Still, she refused to quit. “Tell them all that as soon as I can walk I’m going to fly!” she wrote to friends and fans.

Many people, both black and white, were very impressed by Coleman’s determination. A white businessman helped her buy another plane. By 1926, Coleman was back where she had been before the crash. She wrote to her sister, “I am right on the threshold of opening a school.”

Coleman’s pilot license was issued on June 15, 1921, in France. The year of her birth is incorrect. Bessie Coleman was born in 1892, not 1896.

That spring, Bessie Coleman was invited to perform in Jack- sonville, Florida. Early on the morning of April 30, 1926, Coleman and another pilot took off for a short flight around the airshow field. At first every- thing went smoothly. Then a wrench that had been lying loose in the plane slid into the control gears, jamming them. Suddenly, the plane flipped upside down. Coleman had not strapped herself in, and she fell to the ground. Moments later, the plane crashed, killing the other pilot.

At 34, Bessie Coleman was dead, but her dream survived. In 1929, three years after her death, the Bessie Coleman Aero Clubs were formed. The clubs encouraged and trained African American pilots—just as Coleman had hoped to do. In 1931, the clubs sponsored the first all African American airshow. Bessie Coleman would have been proud.