The Museum of UnCut Funk celebrates some of our favorite Black Activists.

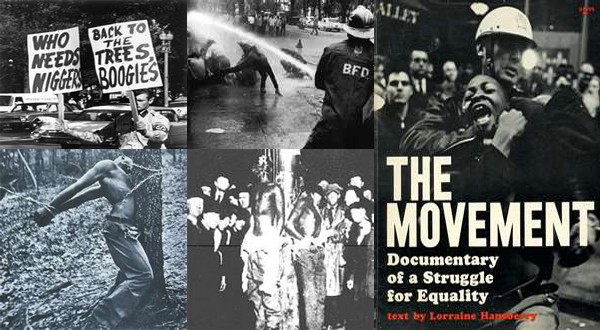

Civil rights activist Fannie Lou Townsend was born on October 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi. The daughter of sharecroppers, she began working the fields at an early age. Her family struggled financially, and often went hungry. Married to Perry “Pap” Hamer in 1944, Fannie Lou continued to work hard just to get by. In the summer of 1962, however, she made a life-changing decision to attend a protest meeting. She met civil rights activists there who were there to encourage Blacks to register to vote. Hamer became active in helping with the voter registration efforts.

Hamer dedicated her life to the fight for civil rights, working for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). This organization was comprised mostly of Black students who engaged in acts of civil disobedience to fight racial segregation and injustice in the South. These acts often were met with violent responses by angry whites. During the course of her activist career, Hamer was threatened, arrested, beaten, and shot at. But none of these things ever deterred her from her work.

In 1964, Hamer helped found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which was established in opposition to her state’s all-white delegation to that year’s Democratic convention. She brought the civil rights struggle in Mississippi to the attention of the entire nation during a televised session at the convention. The next year, Hamer ran for Congress in Mississippi, but she was unsuccessful in her bid.

Along with her political activism, Hamer worked to help the poor and families in need in her Mississippi community. She also set up organizations to increase business opportunities for minorities and to provide childcare and other family services. Hamer died of cancer on March 14, 1977, in Mound Bayou, Mississippi.

[line-sep]

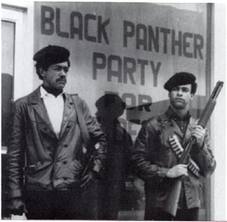

Black political activist, founder, along with Huey Newton, and national chairman of the Black Panther Party, Bobby Seale was born on October 22, 1963 in Dallas Texas. Bobby Seale was one of a generation of young Black radicals who broke away from the traditionally nonviolent Civil Rights Movement to preach a doctrine of militant black empowerment. Following the dismissal of murder charges against him in 1971, Seale somewhat moderated his more militant views and devoted his time to effecting change from within the system.

Seale grew up in Dallas and in California. Following service in the U.S. Air Force, he entered Merritt College, in Oakland, Calif. There his radicalism took root in 1962, when he first heard Malcolm X speak. Seale helped found the Black Panthers in 1966. Noted for their violent views, they also ran medical clinics and served free breakfasts to school children, among other programs.

In 1969, Seale was indicted in Chicago for conspiracy to incite riots during the Democratic national convention the previous year. The court refused to allow him to have his choice of lawyer. When Seale repeatedly rose to insist that he was being denied his constitutional right to counsel, the judge ordered him bound and gagged. He was convicted of 16 counts of contempt and sentenced to four years in prison. In 1970–71 he and a codefendant were tried for the 1969 murder of a Black Panther suspected of being a police informer. The six-month-long trial ended with a hung jury.

Following his release from prison, Seale renounced violence as a means to an end and announced his intention to work within the political process. He ran for mayor of Oakland in 1973, finishing second. As the Black Panther Party faded from public view, Seale took on a quieter role, working to improve social services in black neighborhoods and to improve the environment. Seale’s writings include such diverse works as Seize the Time (1970), a history of the Black Panther movement and Barbeque’n with Bobby (1988), a cookbook.

[line-sep]

James Armistead, the spy and revolutionary, was born into slavery to owner William Armistead around December 10, 1748, in New Kent, Virginia. In 1781, James Armistead volunteered to join the U.S. Army in order to fight for the American Revolution. His master granted him permission to join the revolutionary cause, and the American Continental Army stationed Armistead to serve under the Marquis de Lafayette, the commander of allied French forces.

Lafayette employed Armistead as a spy, with the hopes of gathering intelligence in regards to enemy movements. Posing as a runaway slave hired by the British to spy on the Americans, Armistead successfully infiltrated British General Charles Cornwallis’ headquarters. He later returned north with turncoat soldier Benedict Arnold, and learned further details of British operations without being detected. Able to travel freely between both British and American camps, Armistead could easily relay information to Lafayette about British plans.

Using the details of Armistead’s reports, Lafayette and General George Washington were able to prevent the British from sending 10,000 reinforcements to Yorktown, Virginia. The American and French blockade surprised British forces and crippled their military. As a result of the Lafayette and Washington’s victory in Yorktown, the British officially surrendered on Oct. 19, 1781.

Despite his critical actions, Armistead returned to William Armistead after the war to continue his life as a slave. He was not eligible for emancipation under the Act of 1783 for slave-soldiers, because he was considered a slave-spy, and had to petition the Virginia legislature for his emancipation. The Marquis de Lafayette assisted him by writing a recommendation for his freedom, which was granted in 1787. In gratitude, Armistead adopted Lafayette’s surname.

After receiving his freedom, he moved nine miles south of New Kent, bought 40 acres of land, and began farming. He later married, raised a large family, and was granted a $40 annual pension by the Virginia legislature for his services during the American Revolution. He lived as a farmer in Virignia until his death on August 9, 1830.

[line-sep]

Frederick Douglass was born February 1818, in Tuckahoe, Maryland, U.S. and died on February 20, 1895, Washington, D.C.. Douglass was one of the most eminent human-rights leaders of the 19th century. His oratorical and literary brilliance thrust him into the forefront of the U.S. abolition movement, and he became the first Black citizen to hold high rank in the U.S. government.

Separated as an infant from his slave mother (he never knew his white father), Frederick lived with his grandmother on a Maryland plantation until, at age eight, his owner sent him to Baltimore to live as a house servant with the family of Hugh Auld, whose wife defied state law by teaching the boy to read. Auld, however, declared that learning would make him unfit for slavery, and Frederick was forced to continue his education surreptitiously with the aid of schoolboys in the street. Upon the death of his master, he was returned to the plantation as a field hand at 16. Later, he was hired out in Baltimore as a ship caulker. Frederick tried to escape with three others in 1833, but the plot was discovered before they could get away. Five years later, however, he fled to New York City and then to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he worked as a labourer for three years, eluding slave hunters by changing his surname to Douglass.

At a Nantucket, Massachusetts, antislavery convention in 1841, Douglass was invited to describe his feelings and experiences under slavery. These extemporaneous remarks were so poignant and naturally eloquent that he was unexpectedly catapulted into a new career as agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. From then on, despite heckling and mockery, insult, and violent personal attack, Douglass never waivered in his devotion to the abolitionist cause.

To counter skeptics who doubted that such an articulate spokesman could ever have been a slave, Douglass felt impelled to write his autobiography in 1845, revised and completed in 1882 as Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Douglass’s account became a classic in American literature as well as a primary source about slavery from the bondsman’s viewpoint. To avoid recapture by his former owner, whose name and location he had given in the narrative, Douglass left on a two-year speaking tour of Great Britain and Ireland. Abroad, Douglass helped to win many new friends for the abolition movement and to cement the bonds of humanitarian reform between the continents.

Douglass returned with funds to purchase his freedom and also to start his own antislavery newspaper, the North Star (later Frederick Douglass’s Paper, which he published from 1847 to 1860 in Rochester, New York). The abolition leader William Lloyd Garrison disagreed with the need for a separate, Black-oriented press, and the two men broke over this issue as well as over Douglass’s support of political action to supplement moral suasion. Thus, after 1851, Douglass allied himself with the faction of the movement led by James G. Birney. He did not countenance violence, however, and specifically counseled against the raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia (October 1859).

During the Civil War (1861–65) Douglass became a consultant to President Abraham Lincoln, advocating that former slaves be armed for the North and that the war be made a direct confrontation against slavery. Throughout Reconstruction (1865–77), he fought for full civil rights for freedmen and vigorously supported the women’s rights movement.

After Reconstruction, Douglass served as assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), and in the District of Columbia he was marshal (1877–81) and recorder of deeds (1881–86); finally, he was appointed U.S. minister and consul general to Haiti (1889–91).

[line-sep]

Born a slave, Araminta Ross later adopted her mother’s first name, Harriet. From early childhood she worked variously as a maid, a nurse, a field hand, a cook, and a woodcutter. About 1844 she married John Tubman, a free black.

In 1849, on the strength of rumours that she was about to be sold, Tubman fled to Philadelphia, leaving behind her husband, parents, and siblings. In December 1850, she made her way to Baltimore, Maryland, whence she led her sister and two children to freedom. That journey was the first of some 19 increasingly dangerous forays into Maryland in which, over the next decade, she conducted upward of 300 fugitive slaves along the Underground Railroad to Canada. By her extraordinary courage, ingenuity, persistence, and iron discipline, which she enforced upon her charges, Tubman became the railroad’s most famous conductor and was known as the “Moses of her people.” It has been said that she never lost a fugitive she was leading to freedom.

Rewards offered by slaveholders for Tubman’s capture eventually totaled $40,000. Abolitionists, however, celebrated her courage. John Brown, who consulted her about his own plans to organize an antislavery raid of a federal armoury in Harpers Ferry, Va. (now in West Virginia), referred to her as “General” Tubman. About 1858 she bought a small farm near Auburn, New York, where she placed her aged parents (she had brought them out of Maryland in June 1857) and herself lived thereafter. From 1862 to 1865 she served as a scout, as well as nurse and laundress, for Union forces in South Carolina. For the Second Carolina Volunteers, under the command of Colonel James Montgomery, Tubman spied on Confederate territory. When she returned with information about the locations of warehouses and ammunition, Montgomery’s troops were able to make carefully planned attacks. For her wartime service Tubman was paid so little that she had to support herself by selling homemade baked goods.

After the Civil War Tubman settled in Auburn and began taking in orphans and the elderly, a practice that eventuated in the Harriet Tubman Home for Indigent Aged Negroes. The home later attracted the support of former abolitionist comrades and of the citizens of Auburn, and it continued in existence for some years after her death. In the late 1860s and again in the late 1890s she applied for a federal pension for her Civil War services. Some 30 years after her service, a private bill providing for $20 monthly was passed by Congress.

Source: History Channel, A&E, Wikipedia and Discovery