I am an Olympics junkie. I especially love the summer Olympics, being a track and field fanatic, so this is one of my favorite times in sports. One of the things that I love most about the Olympics is hearing the stories of the athletes. Rarely in sports do you get the back story about the athletes and their struggles to make the team. Then you get to watch their journey as they strive to be the best they can be and beat the best in the world. A very compelling sports two-fer. Most of the stories center around personal triumph or tragedy. However, sometimes the stories are much bigger than the individual athlete and are of greater global importance. And sometimes these stories change history.

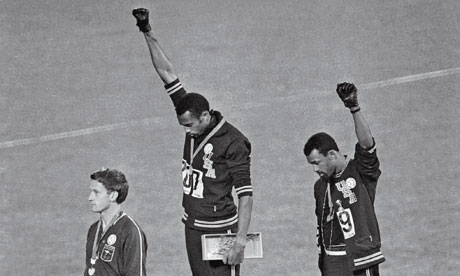

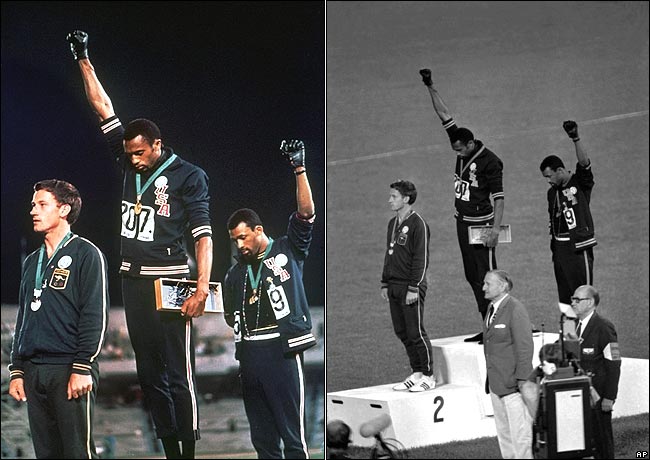

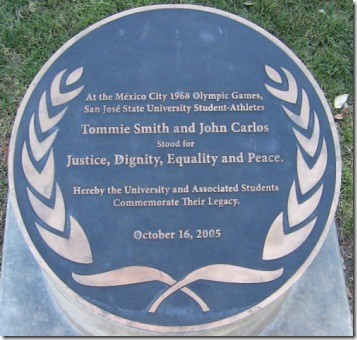

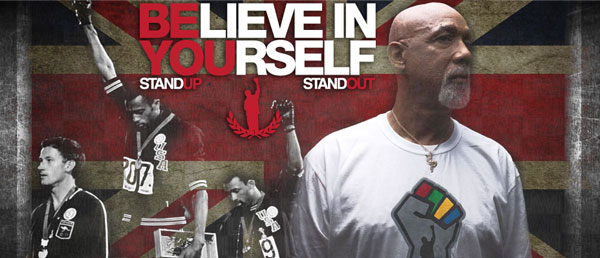

One of the most important stories in Black Olympic history, Black sports history and arguably Black history in general is that of American sprinters John Carlos and Tommie Smith. In a moment that changed history, they elegantly executed a global moment of silence, dressed in black socks and a black glove on the Olympic medal stand. Carlos and Smith’s simple defiant gesture on October 16, 1968 would become one of the most iconic moments in history. I consider both of them to be heroes for having had the courage to make a such a bold Black Power statement on the world stage at a very racially volatile time. History is finally coming around to appreciate what the Black community knew back in ’68 – THEY WERE RIGHT!!!

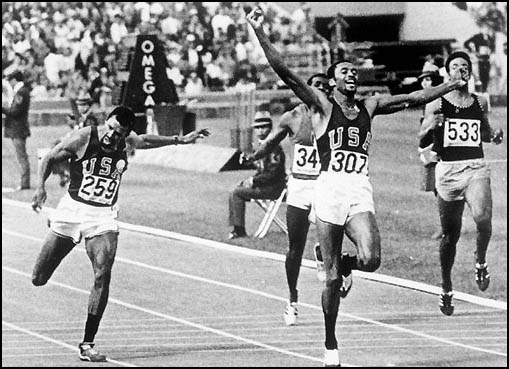

The official results of the 200m race in which they competed was that Tommie Smith won the Gold, Peter Norman from Australia the Silver and John Carlos the Bronze. Tommie Smith set a new record at 19.83 seconds, which stood as the world record until 1979 and the Olympic record until 1984.

John Carlos’s and Tommie Smith’s protest against racial injustice and inequality against Black people and Black athletes in America during the medal stand ceremony produced much less favorable results for them. They wore black socks and no shoes to represent Black poverty. Carlos’s raised left fist represented Black unity. Smith’s raised right fist represented Black Power. Carlos wore his jacket unzipped to represent workers rights. Peter Norman joined the protest by wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) badge.

Carlos and Smith paid a heavy price for their militance. They were kicked off the Olympic team and out of the Olympic village. When they arrived back in the U.S. they received countless death threats and had a hard time finding employment. Australia’s conservative media called for Peter Norman to be punished but his team manager refused to take action against him.

At a press conference after the event Tommie Smith said: “If I win I am an American, not a Black American. But if I did something bad then they would say ‘a Negro’. We are Black and we are proud of being Black. Black America will understand what we did tonight.”

Carlos felt he was put on Earth to to stand up in that moment.

“I had a moral obligation to step up. Morality was a far greater force than the rules and regulations they had. God told the angels that day, ‘Take a step back – I’m gonna have to do this myself.'”

“In life, there’s the beginning and the end,” Carlos said. “The beginning don’t matter. The end don’t matter. All that matters is what you do in between – whether you’re prepared to do what it takes to make change. There has to be physical and material sacrifice. When all the dust settles and we’re getting ready to play down for the ninth inning, the greatest reward is to know that you did your job when you were here on the planet.”

I was pleasantly surprised that Melissa Harris Perry covered politics in sports during her July 22nd show and that one of her guests was John Carlos. The video of this segment is below.

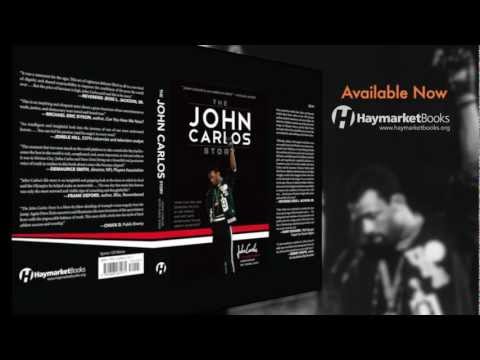

In October, 2011 The John Carlos Story, a book written by John Carlos and David Zihn, a sports writer for The Nation, was introduced. Here is the description of the book: Seen around the world, John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s Black Power salute on the 1968 Olympic podium sparked controversy and career fallout. Yet their show of defiance remains one of the most iconic images of Olympic history and the Black Power movement. Here is the remarkable story of one of the men behind the salute, lifelong activist, John Carlos.

Here is an audio interview with John Carlos and David Zihn and a video interview of them by Democracy now about the book.

Here is a very informative documentary that was produced by the BBC that provides a great overview of what was happening from a sports and a civil rights perspective in the U.S. and specifically at San Jose State with the OPHR leading up to the 1968 Olympic games.

[line-sep]

Here is another interview of John Carlos by Dave Zirin in 2003, marking the 35th anniversary of the 1968 Olympic games.

The Living Legacy of Mexico City an Interview with John Carlos by DAVE ZIRIN

Counterpunch

November 2, 2003

Thirty-five years ago, John Carlos became one half of perhaps the most famous (or infamous) moment in Olympic history. After winning the bronze medal in the 200 meter dash, he and gold medallist Tommy Smith, raised their black glove clad fists in a display of “black power.” It was a moment that defined the revolutionary spirit and defiance of a generation. Now as the 35th anniversary of that moment passes with nary a word, John Carlos talks about about those turbulent times.

DZ: Many call that period of the 1960s, the revolt of the black athlete. Why?

JC: I think Sports Illustrated started that phrase. I don’t think of it as the revolt of the black athlete at all. It was the revolt of the black men. Athletics was my occupation. I didn’t do what I did as an athlete. I raised my voice in protest as a man. I was fortunate enough to grow up in the era of Dr. King, of Paul Robeson, of baseball players like Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella who would come into my dad’s shop on 142nd street and Lennox in Harlem. I could see how they were treated as black athletes. I would ask myself, why is this happening? Racism meant that none of us could truly have our day in the sun. Without education, housing, and employment, we would lose what I call “family hood.” If you can’t give your wife or son or daughter what they need to live, after a while you try to escape who you are. That’s why people turn to drugs and why our communities have been destroyed. And that’s why there was a revolt.

DZ: When you woke up that morning in 1968, did you know you were going to make your historic gesture on the medal stand or was it spontaneous?

JC: It was in my head the whole year. We first tried to have a boycott [to get all Black athletes to boycott the Olympics] but not everyone was down with that plan. A lot of the athletes thought that winning medals would supercede or protect them from racism. But even if you won the medal it aint going to save your momma. It aint going to save your sister or children. It might give you 15 minutes of fame, but what about the rest of your life? I’m not saying they didn’t have the right to follow their dreams, but to me the medal was nothing but the carrot on a stick

DZ: At the last track meet before the Olympics, we left it that every man would do his own thing. You had to choose which side of the fence you were on. You had to say, “I’m for racism or I’m against racism.”

JC: We stated we were going to do something. But Tommie and I didn’t know what we were going to do until we got into the tunnel [on the way to the race].. We had gloves, black shirts and beads. And we decided in that tunnel that if we were going to go out on that stand, we were going to go out barefooted.

DZ: Why Barefooted?

JC: We wanted the world to know that in Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, South Central Los Angeles, Chicago, that people were still walking back and forth in poverty without even the necessary clothes to live. We have kids that don’t have shoes even today. Its not like the powers that be can’t do it provide these things. They can send a space ship to the moon, or send a probe to Mars, yet they can’t give shoes? They can’t give health care? I’m just not naive enough to accept that.

DZ: Why did you wear beads on the medal stand?

JC: The beads were for those individuals that were lynched, or killed that no one said a prayer for, that were hung tarred. It was for those thrown off the side of the boats in the middle passage. All that was in my mind. We didn’t come up there with any bombs. We were trying to wake the country up and wake the world up too.

DZ: How did your life change when you took that step onto the podium?

JC: My life changed prior to the podium, I used to break into freight trains by Yankee Stadium when I was young. Then I changed when I realized I was a force in track and field. I realized I didn’t have to break into freight trains. I wanted to wake up the people who work and run the trains so they can seize what they deserve. It’s like these supermarkets in Southern California that are on strike. They always have extra milk and they throw it in the river or dump it the garbage even though there are people without milk. They say we can’t give it to you so we would rather throw it away. Something is very wrong. Realizing that changed me long before 1968.

DZ: What kind of harassment did you face back home?

JC: I was with Dr. King ten days before he died. He told me he was sent a letter that said there was a bullet with his name on it. I remember looking in his eyes to see if there was any fear, and there was none. He didn’t have any fear. He had love and that in itself changed my life in terms how I would go into battle. I would never have fear for my opponent, but love for the people I was fighting for. That’s why if you look at the picture [of the raised fist] Tommy has his jacket zipped up, and [silver medallist] Peter Norman has his jacket zipped up, but mine was open. I was representing shift workers, blue-collar people, and the underdogs. That’s why my shirt was open. Those are the people whose contributions to society are so important but don’t get recognized.

DZ: What kind of support did you receive when you came home?

JC: There was pride but only from the less fortunate. What could they do but show their pride? But we had black businessmen, we had black political caucuses, and they never embraced Tommie Smith or John Carlos. When my wife took her life; 1977 and they never said, let me help.

DZ: What role did you being outcast have on your wife taking her own life?

JC: It played a huge role. We were under tremendous economic stress. I took any job I could find. I wasn’t too proud. Menial jobs, security jobs, gardener, caretaker, whatever I could do to try to make ends meet. We had four children, and some nights I would have to chop up our furniture and put it in the fireplace to stay warm. I was the bad guy, the two headed dragon-spitting fire. It meant we were alone.

DZ: Many people say athletes should just play and not be heard. What do you say to that?

JC: Those people should put all their millions of dollars together and make a factory that builds athlete-robots. Athletes are human beings. We have feelings too. How can you ask someone to live in the world, to exist in the world, and not have something to say about injustice?

DZ: What message do you have to the new generation of athletes hitting the world stage?

JC: First of all athletes black/red/brown/yellow and white need to do some research on their history; their own personal family They need to find out how many people in their family were maimed in a war. They need to find out how hard their ancestors had to work. They need to uncloud their minds with the materialism and the money and study their history. And then they need to speak up. You got to step up to society when it’s letting all its people down.

DZ: As you look at the world today, do you think athletes and all people still need to speak out and take a stand?

JC: Yes, because so much is the same as it was in 1968 especially in terms of race relations. I think things are just more cosmetically disguised. Look at Mississippi, or Alabama. It hasn’t changed from back in the day. Look at the city of Memphis and you still see blight up and down. You can still see the despair and the dope. Look at the police rolling up and putting 29 bullets in a person in the hallway, or sticking a plunger up a man’s rectum, or Texas where they dragged that man by the neck from the bumper of a truck. How is that not just the same as a lynching?

DZ: Do you feel like you are being embraced now after all these years?

JC: I don’t feel embraced, I feel like a survivor, like I survived cancer. It’s like if you are sick and no one wants to be around you, and when you’re well everyone who thought you would go down for good doesn’t even want to make eye contact. It was almost like we were on a deserted island. That’s where Tommy Smith and John Carlos were. But we survived.

Dave Zirin writes about the politics of sports for the Nation Magazine. He is their first sports writer in 150 years of existence. Winner of Sport in Society and Northeastern University School of Journalism’s 2011 ‘Excellence in Sports Journalism’ Award, Zirin is also the host of Sirius XM Radio’s popular weekly show, Edge of Sports Radio.

[line-sep]

You can learn more about John Carlos and Tommie Smith here:

“The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World”

http://www.booktv.org/Program/12969/The+John+Carlos+Story+The+Sports+Moment+That+Changed+the+World.aspx