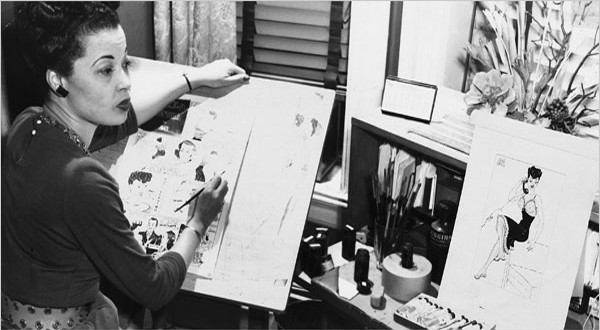

Women’s History month is a very special time at the Museum Of UnCut Funk. As we celebrate the accomplishments of women in every aspect of American History, we are focusing on women in the arts. To help us make this year’s celebration more note worthy we are honored to have Nancy Goldstein, author of Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist, as a guest content contributor.

Thank you Nancy.

My 2008 biography, Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist (University of Michigan Press) explores Ormes’s remarkable life and her social and political commentary in her comics and cartoons. But missing from the book are discussions of two topics that Ormes often featured: romance and fashion. Other writers have also overlooked these topics, even though they were central to Ormes’s narrative and certainly to her life. Perhaps we believed these topics were “too frivolous” or, worse in the comics world, “of feminine interest,” like pulp paperbacks or fashion magazines. Now that we are in the middle of Women’s History Month, it seems fitting– and enjoyable–to discover new aspects of this pioneering woman’s artistic production and to remedy those omissions.

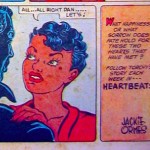

Most of her work appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the largest black press weekly newspapers that by the late 1940s claimed a coast-to-coast readership of over a million through its fourteen big city editions. Jackie Ormes (1911-85) produced four different comic strips and cartoons from 1937 to 1956, a time period that includes an unexplained seven-year break from cartooning: Torchy Brown in “Dixie to Harlem,” 1937-38; Candy, for four months in 1945; Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, 1945-56; and finally Torchy in Heartbeats, the comic strip that best exemplifies our topics of romance and fashion, and the one that will be the focus of this discussion. Torchy in Heartbeats appeared in a full color, eight-page tabloid-size insert in the Pittsburgh Courier from 1950-54, along with other strips that featured a lineup of African American cowboys, space rangers, detectives, crime fighters, fighter pilots, and secret agents.

Torchy in Heartbeats chronicled the adventures of a mature, independent woman who took on serious issues of race and environmental pollution as she sought true love, a topic unusual for its time since black characters were rarely seen in love scenes in print or film. Indeed, in the mainstream media passionate, fulfilling, or even enduring love relationships between African American men and women were virtually invisible. Like Ormes’s more political cartoons and comics, Torchy in Heartbeats served to advance the cause of pride and racial uplift, important to the Pittsburgh Courier’s editors and columnists, community leaders, and other African Americans.

Nineteen-fifty was a banner year for romance fiction. “Love was on the racks everywhere. . . .more love begat more love,” Michelle Nolan explains in her book Love on the Racks. “In 1949, comic book publishers learned there was nothing more super than a kiss” and 22 companies parlayed the frenzy by churning out 256 romance issues under 118 titles like Young Romance and First Love. When the Courier tapped Ormes to draw for the launch of their full color Comic Section insert, she jumped at the chance to bring this best-selling genre to the pages of a newspaper.

Torchy in Torchy in Heartbeats personified the desire for economic freedom, self-improvement, and emotional happiness that would resonate with Ormes’s readers. Young woman Torchy left home and ventured into the world, meeting new and sometimes tragic loves along the way. In contrast to the often sexually scandalous stories in women’s magazines, Torchy provided a model for virtuous behavior. Torchy in Heartbeats appeared in a family newspaper, one that was known for its editorials and features promoting good behavior, thrift, manners, and family values, all elements of racial uplift that the Courier promoted.

And Torchy was attractive, with a pretty face and shapely body. Readers understood that a romance required the woman searching for love to project sex appeal and desirability in order to attract the man of her dreams. The image of a comely and sometimes partially clad black female in heroic performance fit perfectly with the Courier’s effort to be at once eye-catching and racially uplifting at the same time, countering the demeaning images in mainstream comic strips where black women were stuck in what were meant to be humorous mammy-type roles, or as domestic servants and laundresses with oversized, lumpy clothing covering portly bodies.

By early 1951 Ormes was producing fashion shows and training models on the South Side of Chicago and she was intimately as well as commercially involved with dressing the female body in the latest styles. Soon she added Torchy Togs to her comic strip, a paper doll cut-out panel that often covered half the Torchy page. Here Torchy wore a variety of smart American sportswear, Paris-style evening dress, and occasionally ordinary clothing, sometimes athletic, easy, and comfortable and other times elegant, feminine, and ladylike. In what is undoubtedly a unique narrative device for paper doll cut-outs, Torchy speaks directly to readers, telling them how and when to wear their clothes. In one Torchy Togs panel, for instance, she is in a bra, girdle, and nylons, and says, “These undergarments are a must for proper grooming.” This was valuable advice for the young African American woman reader following her mother’s and grandmother’s admonitions to wear proper and respectable clothing that would, incidentally, defy white stereotypes of the loose black female in revealing clothing, or in clothing that fit poorly.

Fashions are attuned to the seasons, and Torchy provides apt descriptions, like “Want to whirl in his arms as gay as an autumn leaf? Then try this date dress with the large leaf pattern” and “Here are four neat little numbers for my summer weekend trip.” In 1951, at the height of the Korean War, Torchy shows “a romantic quartet of fashion hints just for those days when your fighting man comes home on leave.” Indeed the paper doll clothing is a panoply of early 1950s fashion, with such styles as full or pleated skirts, toreador pants, cocktail dresses, and one-piece bathing suits with matching cover-ups. Ormes describes materials and cut in detail, verbally reveling in luxury fabrics as in these side commentaries: “A silk shantung hostess gown—royal blue with gold pleated chiffon draped diagonally.” Other times, she compares her clothing to couture designs by Christian Dior, or “a famous designer,” or drops the name of Artie Wiggins, a well-known African American hat designer in Chicago. Indeed Torchy’s sumptuous wardrobe leaves little doubt of her high expectations and that her search for love will end, predictably, in a happy marriage that provides material well-being.

Just as Torchy was instructing women on how to dress in Torchy Togs, she was also modeling ways to learn from risky relationships and love experiences in the Torchy in Heartbeats narrative. As the first episode winds down, Torchy finally comprehends what readers knew all along, that her pianist boyfriend was more in love with his music than with her. With large, sad, wet eyes and knitted brows, Torchy figures it out, “Am I being a fool? Am I looking for something that can’t be had?” She leaves him and seeks true love elsewhere, encountering thrilling adventure, and escaping danger, as in one shocking scene of attempted rape, unheard of in newspaper comic strips. Torchy in Heartbeats wound down in 1954, but faithful readers were rewarded when our heroine found the ideal romance, one with the emotional support that promises a happy ending, namely a proposal of marriage from an upstanding man.

Combining as they usually do both text and art, cartoons and comic strips depend on a visual vocabulary to say what words fail to convey. Torchy’s fashions visually delineated lifestyle in ways far more nuanced and complex than most other black press comics, implying material consumption as a marker of economic prosperity and entry into the middle class. Her pending marriage to a heroic man completes the romantic dream. But the first step, Jackie Ormes’s smart and willful characters implied, was a shopping trip to the finest store; it was understood that the next step would be employment at the store, a role in management, and, maybe one day, even ownership.

# #

An indepth study of romance in Jackie Ormes’s complete oeuvre can be found in Black Comics: Politics of Race and Representation (Bloomsbury Academic, March 14, 2013), Sheena C. Howard and Ronald L. Jackson II, editors.

##

-

- August 19, 1950. This is the first full color Torchy comic strip. The strip would later be titled Torchy in Heartbeats. Recently the University of Michigan Special Collections Library acquired heretofore lost Comic Section issues starting with this one through early 1951

-

- January 8, 1950. Torchy’s first mistake was involvement with Dan. She thought she could reform his illegal gambling and running around with other women, but she ended up suffering in the name of love.

-

- January 8, 1950. Torchy’s first mistake was involvement with Dan. She thought she could reform his illegal gambling and running around with other women, but she ended up suffering in the name of love.

-

- 1951. Torchy’s next love was Earl, a musician who had been injured in a bus crash. While Ormes spun out the romance story on one part of the page, her Torchy Togs paper doll cut-outs reported the latest in fashion.

-

- 1951. Torchy’s next love was Earl, a musician who had been injured in a bus crash. While Ormes spun out the romance story on one part of the page, her Torchy Togs paper doll cut-outs reported the latest in fashion.

-

- May 16, 1953. Purple prose and flowery writing were essential ingredients of romance fiction. Torchy triumphs in the end when Paul proposes marriage. He embodies the reality of male power that Torchy needs to ensure her survival in a cruel world, yet he is tender and gentle, loving her, protecting her, and putting concern for her above all else.

For more information on Nancy Goldstein and Jackie Ormes please visit: http://www.jackieormes.com/

1 Comment

This is so cool. Thank you for documenting this.