Keeping It Real and Making It Funky…June is Black Music Month. Celebrate the best clubs of Harlem’s past and the great artists that performed in them with the Museum Of UnCut Funk.

Connie’s Inn was located along Harlem’s Boulevard of Dreams, the unrecognized venue was the property of Conrad “Connie” Immerman. The Harlem bootlegger transformed the saloon into a 500-seat nightclub and added a stage large enough to hold more than 30 performers and musicians. It received little attention in comparison to the Cotton Club, but it boasted performances from Louis Armstrong, Moms Mabley and Fletcher Henderson.

Connie’s Inn and the Cotton Club both allowed Black performances, but only for white audiences. Very few Blacks gained admission to either venue, and countless wealthy ones were turned away. Connie’s Inn refused admittance to Charles Gilpin, renowned actor of the 1920s.

Still, Connie’s Inn was different in that Black artists and workmen designed it. Immerman also claimed the club’s exclusive policy was solely profit-driven. Whereas Cotton Club owner Owen Madden reproduced stereotypes of the plantation South and encouraged performers to play “jungle music.”

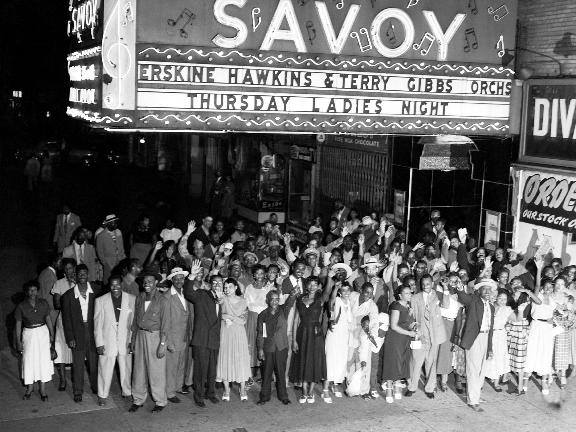

The Savory was the first and only integrated ballroom in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance. “We didn’t have segregation at the Savoy,” said Norma Miller – famous Lindy Hopper of the Harlem Renaissance. “The Savoy opened the doors for all people being together.”

Erected between 140th and 141st streets, the Savoy Ballroom was one of the first racially integrated venues in the country. Erected in 1926, the dance hall was the go-to spot for dance amongst Harlem’s diverse racial and social groups. Harlemites followed its mirrored walls and marble steps to the block-long dance floor. Across it were double bandstands, the stages for the Savoy’s famous battle of the bands.

In 1927, the Dixie Syncopators, Harlem Stompers, and Roseland Orchestra competed in a “Battle of Jazz” competition, and later other bands led by Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington would do the same. These bands shook the walls of the Savoy and lured everyone to the dance floor. Nicknamed the “Home of Happy Feet,” the Savoy was the birthplace of the countless rhythm dances. It inspired the signature dance of the era, the Lindy Hop. The quick box step was a favorite among the famous and everyday Harlemites, and the Savoy provided the largest stage for its display in New York City.

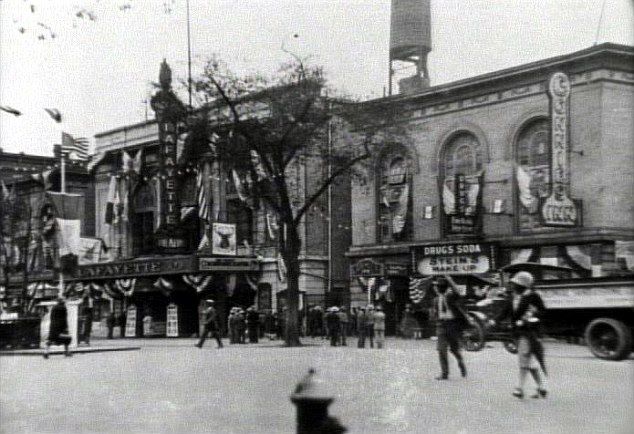

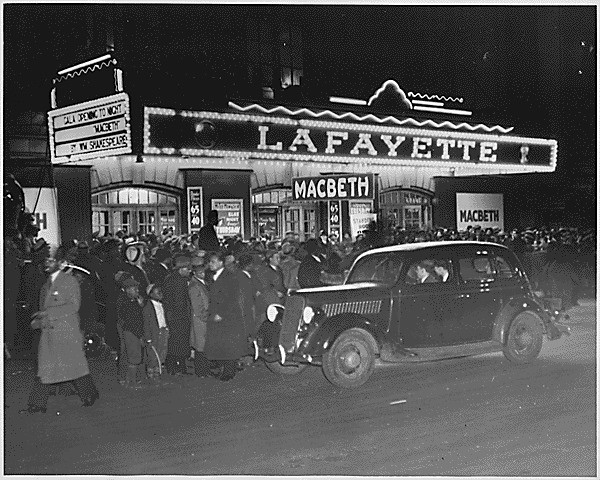

At the center of Harlem’s theatrical district was the Lafayette Theatre. Built in 1912, the theatre stood in a class of its own as the first theatre to cater to Black audiences. It desegregated as early as that year, allowing Black patrons to sit in orchestra seats in addition to balcony seats. The Lafayette was also one of the first to disrupt the long-established ban against interracial stage performances with its presentation of The Emperor Jones. The Eugene O’Neill production held 490 performances throughout the 1920s at the Lafayette.

The theater hosted various performances with its production of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” noted as one of its best. The 1936 play was the project of the Negro Theater Project – an economic recovery program aimed at providing employment to African American actors, playwrights, directors and theater technicians. It was an enormous success with over 10,000 people arriving to gain one of Lafayette’s 1,223 seats on opening night. Featuring an all-Black cast and set in 19th century Haiti, the production entranced all its patrons and would eventually have an extended run.

Before its feature in Spike Lee’s “Jungle Fever,” the Renaissance Casino and Ballroom was one of the most happening venues for Blacks throughout the Harlem Renaissance. Built in 1924, the “Rennie” was the only building founded and operated by a Black businessmen.

The three owners were Caribbean immigrants who used the venue to host the area’s political meetings, elegant parties, and sporting events. Included in the events were the exhibition games of the country’s first professional Black basketball team – the Harlem Renaissance, also known as the Rens. The Rens developed its 40-year winning streak on the venue’s ballroom floor. When it did not host sporting events, the “Rennie” filled its 900-seat theatre with Harlemites eager to see its film screenings and stage acts.

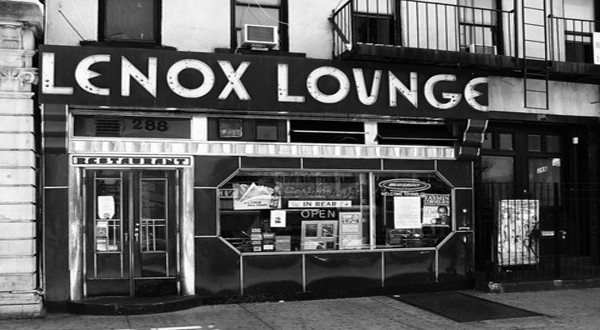

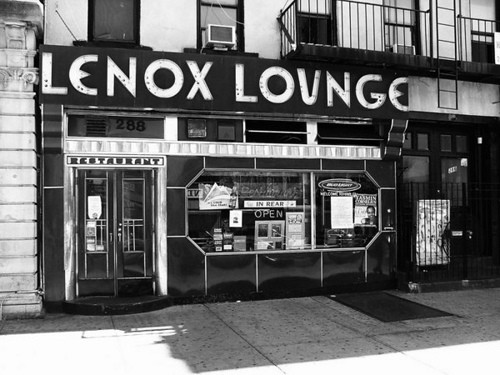

Lenox Lounge was a long-standing bar in Harlem, New York City. It was located in 288 Lenox Avenue, between 124th and 125th. The bar was founded in 1939 by Dominic Greco and served as venue for performances by many great jazz artists, including Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, and John Coltrane. Harlem Renaissance writers James Baldwin and Langston Hughes were both patrons, as was Malcolm X.

The bar deteriorated through the middle of the 20th century. Alvin Reid, Sr. purchased it in 1988 and restored the original Art Deco interior from September 1999 to March 2000, during the only closure in the bar’s history. The Lenox Lounge was voted “Best of the Best” by the 2002 Zagat Survey Nightlife Guide and by the 2001 New York Magazine. In 2012, a rent increase threatened to shutter the establishment.

In December 2012, it was announced that it would closed at the end of the year. However in January 2013 Reed said he was reopening at 333 Lenox Avenue and that it would have its iconic neon sign there. Richard Notar, who owned the Nobu Restaurant chain and who took over the lease on the original 288 Lenox location, said he would maintain the decor of the original 288 lounge which does not yet have a name.