In a time of debt ceiling debates, federal budget cuts and the possible reduction in US military spending, I thought it would be befitting to highlight some of the koolest military / war related comic books I could find, many of which are archived in the collection of The Museum of UnCut Funk. As I continue to research military comics and their portrayal of Blacks and other minorities, The Museum of Uncut Funk has created an online exhibition of the comic books presented in this blog.

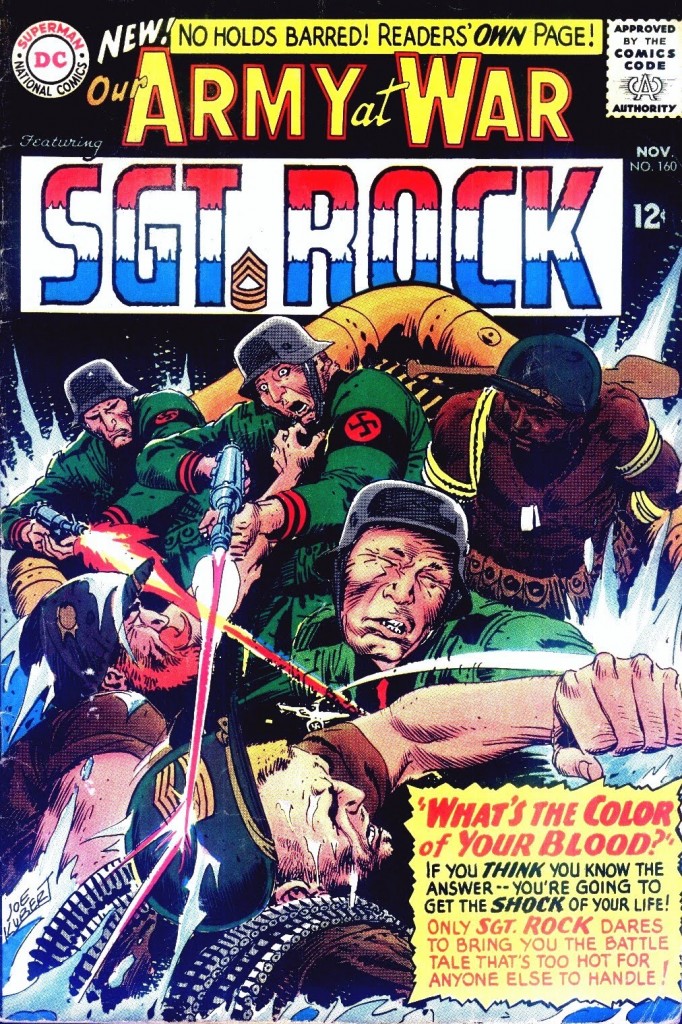

The Sgt. Rock & Easy Co. story in DC’s Our Army At War #160 (November 1965) again features Jackie Johnson. The story retcons a heavyweight boxing champ background for Jackie, with him having lost the title prior to enlisting, to a Nazi paratrooper, whom he meets again on the battlefield. Rock, Wild Man, and Jackie are captives of the Nazi scum, and the Nazi heavyweight boxer gives Jackie a rematch, with the intent of beating Jackie into submission and getting him to admit his blood is a different color than that of the ‘Master Race’. As he watches Jackie deliberately take a beating (to avoid Rock and Wild Man getting killed in retaliation, should he beat the Nazi in the bout) but stubbornly refuse to give the Nazi his satisfaction, Rock recalls seeing Jackie in the ring at Madison Square Garden when he was a boxer himself, watching Jackie for pointers on how to fight well. Rock had recognized then the additional burden Jackie had been carrying, of having to prove himself twice over, as an individual fighter, and as an African American. When Jackie had eventually won the title, and then lost it to the Nazi, the latter had taken the opportunity to use his victory as propaganda for the supposed superiority of the ‘Master Race’ – WWII was a war about racism.

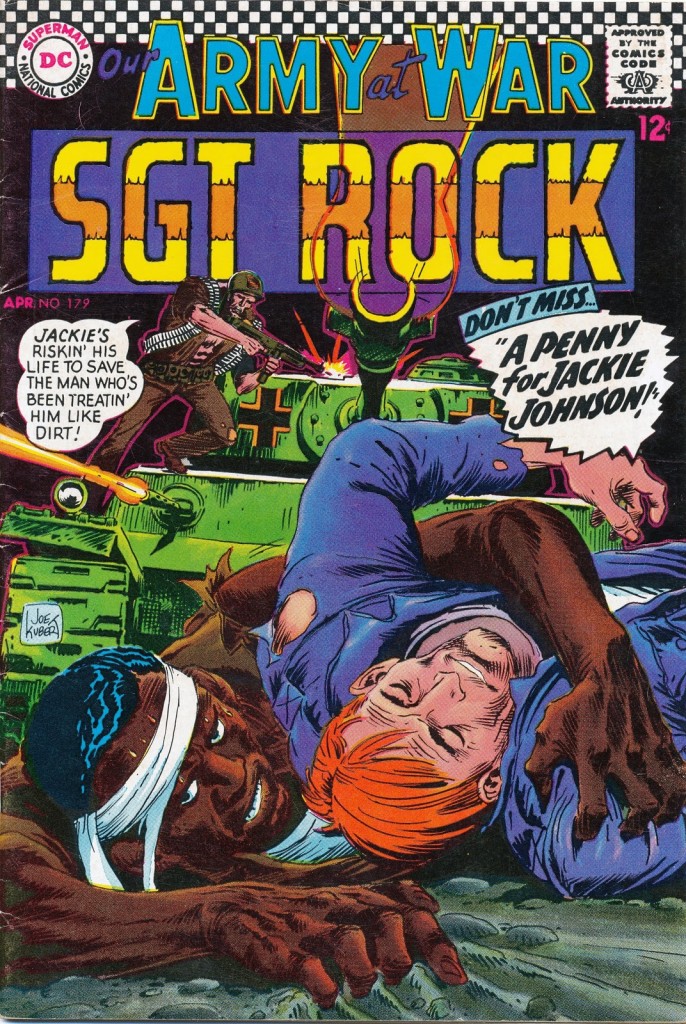

This Kanigher/Kubert Jackie Johnson story in the April 1966 issue of Our Army At War (179) is reminiscent of the Lee/Kirby story in Sgt. Fury 6 of a few years earlier. One of Bob Kanigher’s specialties was the writing of anti-racist comics, and many of the few 1960s comics to address this issue were by him. The tension between the tolerant Johnson and the bigoted Sharkey, who, from the moment he joins Easy, harasses the Black soldier, recalls the sparring between Gabriel Jones and George Stonewell in Sgt. Fury 6. Sharkey represents a stereotype of sorts himself – he identifies himself as from the mountains, suggesting a fairly remote white community hanging onto antebellum racist values. Sharkey also voices a stereotypically negative opinion of the reliability of Black fighters/soldiers. Although set in WWII, in which there were few instances when white and Black soldiers fought side by side, the anti-racist messages in both the Sgt. Rock and Sgt. Fury stories appear aimed at combating the racial tension that at the time was tearing apart the U.S.military, especially in Vietnam, as well as civilian society.

In 1985, in an attempt to perhaps undo historical omissions, the Sgt. Rock comic book (DC Comics) released a two-part series dedicated to honoring the contributions of Blacks in World War II. Book One of the series detailed the early days of the formation of the all-Black fighter pilots from Tuskegee Institute (#406). A great easy-to-read reference resource for any young historian or civil rights enthusiast, it has a terrific story about the trials of the Tuskegee Airmen. DC Comics used the Sgt. Rock series a number of times in the 60s, 70s and 80s to present stories dealt with issues of racial hatred and bias. In addition to this issue, Sgt. Rock issues 405 and 406 are a part of the The Museum of UnCut Funk archive.

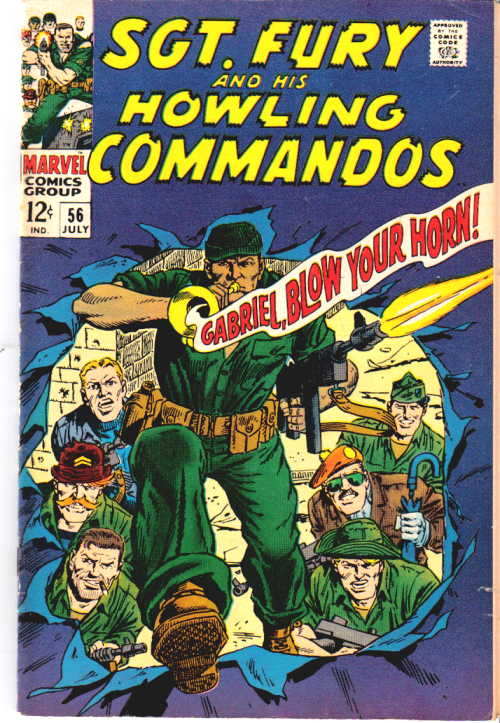

Even though in reality there were no integrated military units in the armed forces during World War II, Stan Lee at Marvel Comics didn’t let that stop him from creating one of the most imaginative commando units in all comic history: Sgt Fury and his Howling Commandos. There is a rumor that the title of this book started as a joke, it was one of the best war comic book series ever created. Where most war comics up to that time were severely lacking in lighthearted fare, these guys actually made readers laugh. The group was made up of an Englishman, a southern rebel, an ex-circus strongman, a mechanic from Flatbush, an Italian movie star and a German born pilot and yes, a Black musician (Gabriel Jones). They were all led by a tough warhorse from Hell’s Kitchen, Fury. If you are going to re-write the racial and ethnic history of the American military, why not make it as diverse as you can? Gabe was treated as an equal member of the team, and even starred in several solo stories that dealt with prejudice and racial hatred. Stg. Fury and his Howling Commandos are archived in the collection of The Museum of UnCut Funk.

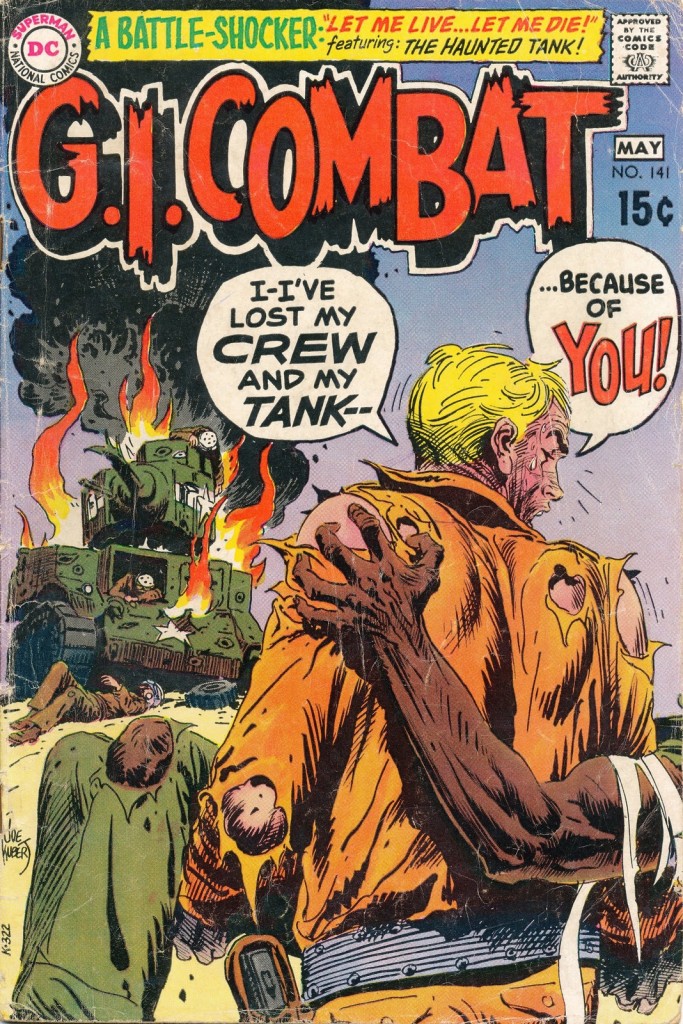

Joe Kubert’s cover of G. I. Combat 141, like many DC covers from the late 60s or very early 70s, is somewhat misleading. Taken at face value, and it’s the word balloons that do it, the cover suggests to readers that in the story the Haunted Tank is going to be destroyed, and that somehow it will be the fault of a Black man. Quite why DC would want to create the latter impression is curious, because Robert Kanigher’s story reads with an integrationist, anti-racist message. The story begins with the Haunted Tank crew re-stocking with ammunition from a supply depot manned by a segregated Black unit, much as would have often been the case in WWII.

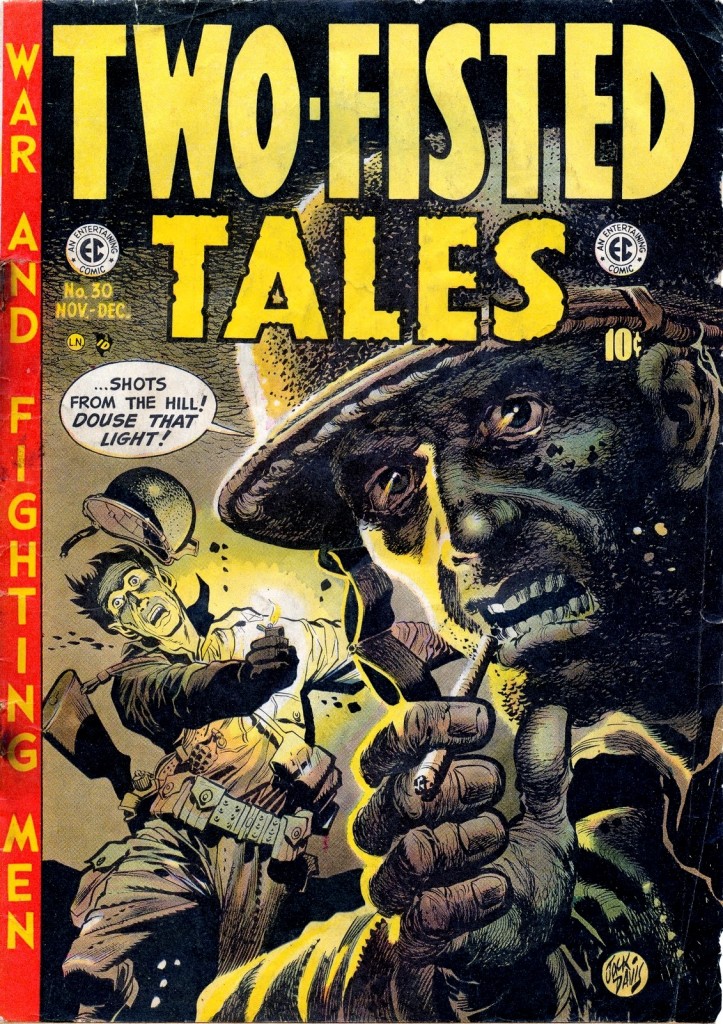

The first occasion that I am aware of on which comics addressed the issue of inter-racial strife within the US armed forces was in Two-Fisted Tales 30 (Nov-Dec 1952), in the story “Bunker!”, written by Harvey Kurtzman and drawn by Ric Estrada, with colors by Marie Severin. The famous cover of this issue is by Jack Davis. The plot of “Bunker!” is straightforward. There’s some Chinese soldiers holed up in a very strategically placed bunker, pinning down two platoons of U.S. troops, one segregated Black and the other segregated white. The two groups of American men are on different sides of the bunker, each trying to take the hill on which it is located.

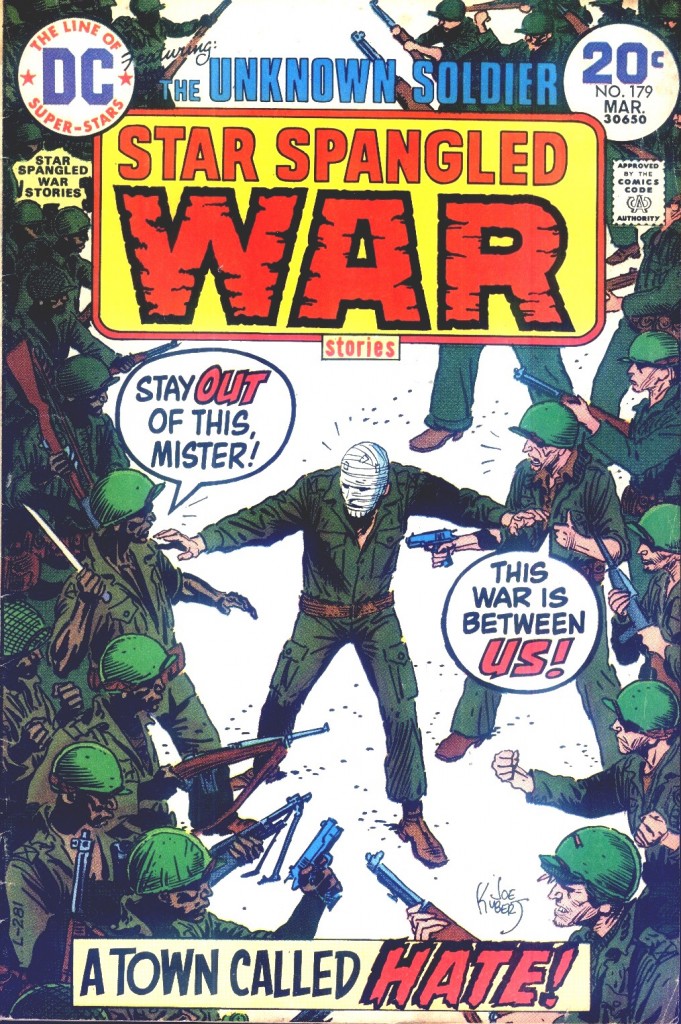

With Archie Goodwin as editor, this issue of Star Spangled War Stories #179, March 1974 features an Unknown Soldier story that exposes the intense racial infighting that had been a serious problem in the U.S. military during the Vietnam conflict, using a WWII setting. In the Armed Forces Journal in 1971, Col. Robert D. Heinl, Jr. wrote: “The morale, discipline and battleworthiness of the U.S. Armed Forces are, with a few salient exceptions, lower and worse than at any time in this century and possibly in the history of the United States. By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous. Elsewhere than Vietnam, the situation is nearly as serious. Intolerably clobbered and buffeted from without and within by social turbulence, pandemic drug addiction, race war, sedition, civilian scapegoatise, draftee recalcitrance and malevolence, barracks theft and common crime, unsupported in their travail by the general government, in Congress as well as the executive branch, distrusted, disliked, and often reviled by the public, the uniformed services today are places of agony for the loyal, silent professionals who doggedly hang on and try to keep the ship afloat.”

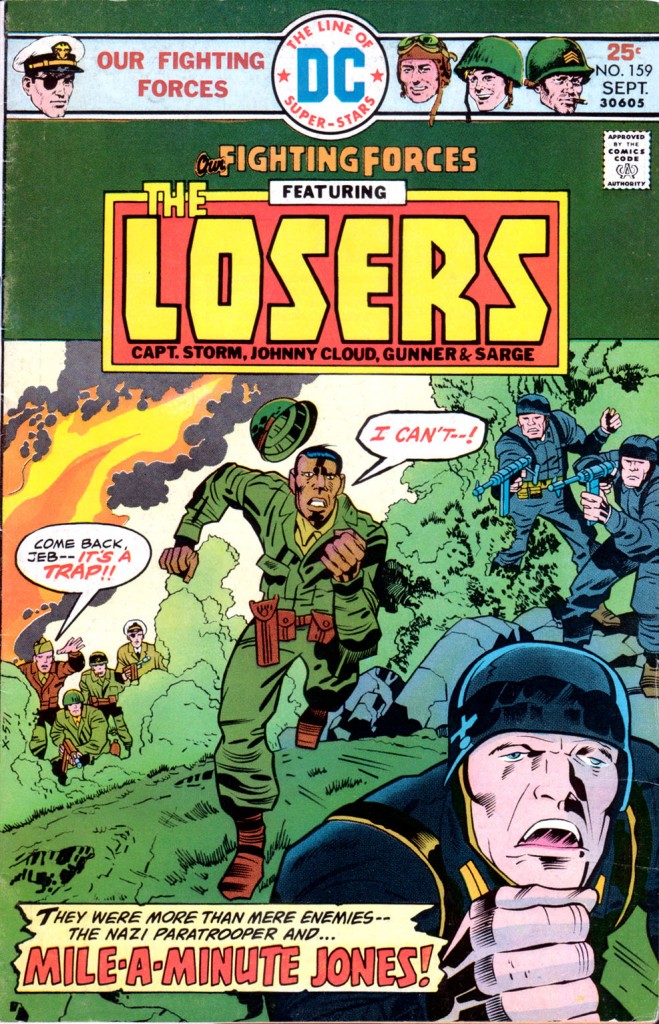

A Jack Kirby Losers story in Our Fighting Forces 159 (Sept 1975) features a one-off appearance of Mile-a-Minute Jones, a Black soldier. Kirby appears to have played on Bob Kanigher’s idea of making Jackie Johnson a world heavyweight boxing champ like the real life Joe Louis from the mid-20th century, by modeling his character on Jesse Owens, the Olympic champion athlete who won golds at the 1936 Games in front of Adolf Hitler, much to the Fuhrer’s annoyance.

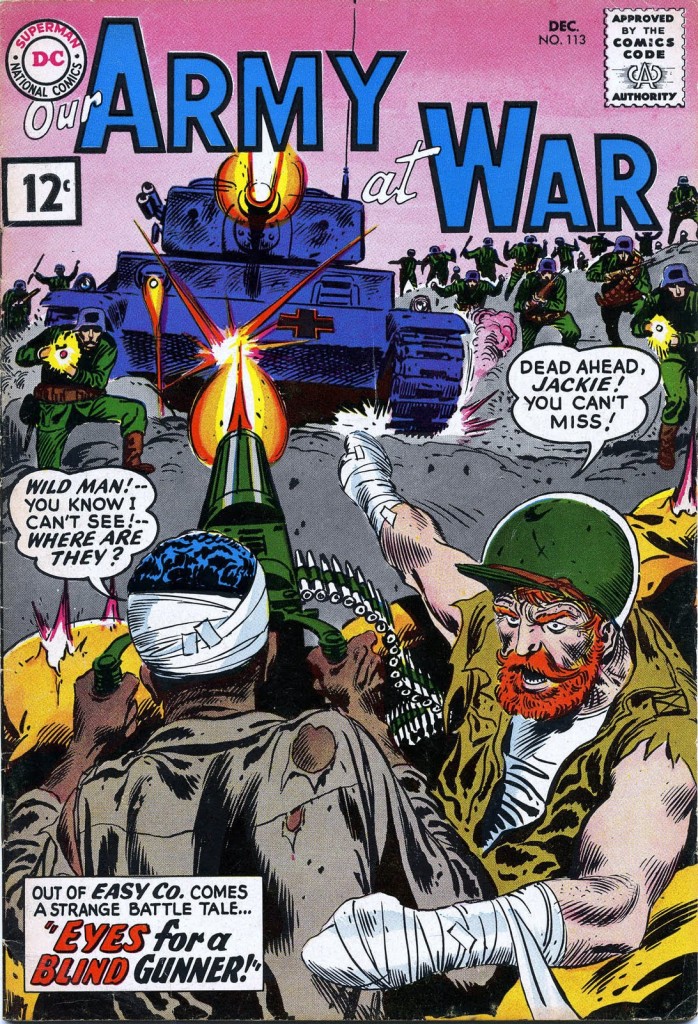

DC’s Our Army At War 113 (December 1961) appears to be the earliest example of a racially integrated comic book that doesn’t use insulting stereotypical images of Blacks. As I read the story I didn’t pick up any hint of racial prejudice. The artwork is fantastic, even for Joe Kubert. It’s also a well-written piece. The most significant thing about it, though, is that race is not overtly identified as an issue even though a Black character is one of the main protagonists in this one. At the time it was published this was an extremely revolutionary thing to do in comics. The members of Easy Co. act towards each other as if they are close buddies. It is a very powerful statement of the way things should be. The similarity (in appearance) between Wild Man and Dum Dum Dugan of the Howling Commandos is interesting. It does appear that Lee and Kirby could have built on this idea of an integrated platoon when they launched Sgt. Fury early at the end of 1962.

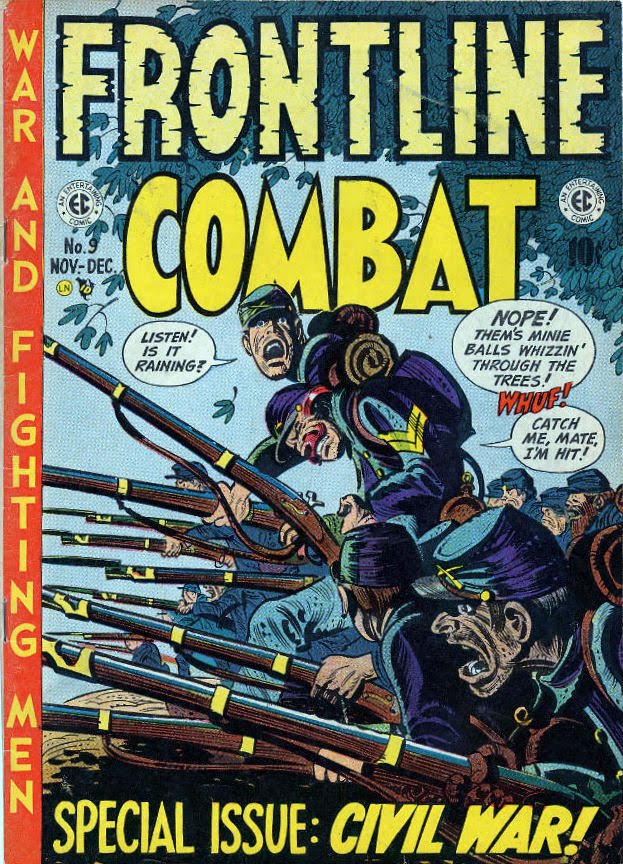

The comic is EC’s Frontline Combat 9 from Nov/Dec 1952. It’s an all-Civil War special, and the first story in the book is the focus of this post. Titled simply “Abe Lincoln!”, key events in the life of Honest Abe leading up to the outbreak of war are narrated by an old country guy sitting in his chair by the fire in his Charleston, South Carolina home. As the tale unfolds we see our narrator only from behind, or the lower part of his body, but never his face. Not, that is, until the last page. He speaks in what is identifiable as a Southern drawl, which has characteristics that might make you suspect he’s Black, and that perhaps resonates with movie stereotypes of Blacks from the South. I don’t think there was any disrespect whatsoever intended by the the writer, Harvey Kurtzman, in this instance. It reads like a genuine attempt to get at a real Black character, but there’s no confirmation of this identity for the reader until the very last panel. The last three panels show the narrator up from his chair and coming out of his front door, but only at the very end does the light reveal his face and we see that he is an elderly Black gentleman. Having witnessed the event that marked the beginning of the Civil War, he prays for Lincoln’s well-being.

Sources: Black Science Fiction, Professor Robert Foster, KB and Out Of This World

2 Comments

Great blog. So sad about Joe Kubert’s passing. 85 years doesn’t seem long enough.

Where can I purchase original Haunted Tank comic books from the 1960’s. Thanks