Our Funky Turns 40: Black Character Revolution Exhibition National Museum Tour was recently covered by Tanya Ballard Brown for NPR’s Code Switch blog. Below is Tanya’s article, which includes her conversation with legendary animator Leo Sullivan, who worked on the Fat Albert cartoon special and series and several other 1970’s cartoons that featured positive Black characters.

Birds Eye View

Animator Leo Sullivan helped develop some of the characters and storylines on Fat Albert.

“Doing the cartoons and developing those shows and working on them in those early days was exciting,” he says. “It was more personal, it took more people to do them, it was more expensive, and in my day we had to individually develop characters.”

Sullivan started working as an animator in 1961, and over the years worked on lots of what I watched while sitting cross-legged in front of the TV on Saturday mornings, including The Flintstones, Scooby Doo, Captain Caveman, Richie Rich and the Laff-A-Lympics, just to name a few.

Today, at 71, he teaches kids about the technology and animation for the games they play.

“We felt what better way to introduce kids to the science fields, because they play these games, but they don’t know how that stuff works,” Sullivan says. “We teach them in these classes how the technology works and how they can be a part of it, giving them the skills in case they want to continue doing it in high school, college, or at a trade or technical school.”

——–

As a kid growing up during the 1970s and ’80s, I would often spend the night at my cousin Chris’ house. On Friday nights after my aunt sent us to bed and turned off the light, we would lay in our respective bunk beds whispering to each other — not about school, or friends or toys (well, OK, sometimes about toys), no, we were locking down our cartoon watching plan for the next morning. Top of the list?

Hey, hey, heyyyyy, it’s Faaaaat Albert!

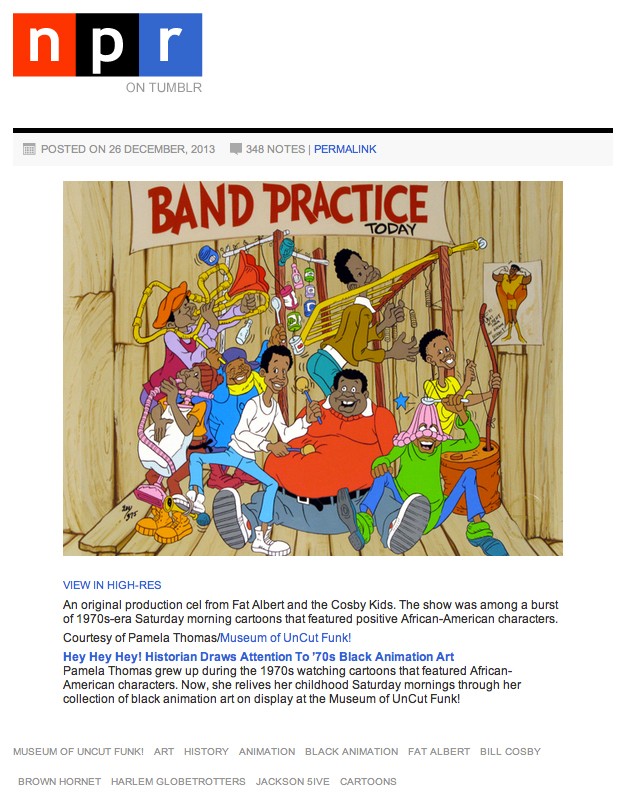

Yep, that catchy phrase kicked off each episode of Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids. Actor and comedian Bill Cosby created and produced the show, which aired from 1972 to 1985, and based it loosely on his childhood. Fat Albert and the gang (which included a character named Mushmouth and another named Dumb Donald — I’m guessing that wouldn’t fly today) hung out in North Philadelphia and faced many moral crises. Chris and I (and a bunch of you, too, you know it!) loved the kids’ various shenanigans and the life lessons.

Most episodes ended with a similar catchy tune from the cobbled together instruments of the Junkyard Band. In fact, music was a common theme among many of the new entries to that era’s Saturday morning cartoon lineup.

UnCut Funk!

Pamela Thomas was particularly captivated by the animated images of African-Americans on Fat Albert and other shows from that era, including The Jackson 5ive, Josie and The Pussycats and Harlem Globetrotters.

“I was born in the ’60s, so I was growing up in the ’70s and I remember all of these cartoons — not all of them — but this is the first time that all of these positive animated images were on TV,” says Thomas, a preschool teacher who grew up in the Bronx.

“Their stories were like your stories, their experiences were like your experience,” says Thomas, who has a black history degree from The City College of New York. “Bill Cosby’s cartoon was so groundbreaking, it just dealt with so many issues — smoking, cheating in school, playing hooky, divorce, what happens when you steal from others. You don’t realize it when you’re watching it that you’re getting all of these messages in a form that children can understand.”

Twelve years ago, Thomas started collecting black animation art, and a few years later she started the online Museum of UnCut Funk! Now, she has acquired enough pieces for a traveling show, Funky Turns 40: Black Character Revolution Exhibition, which makes its first stop in January at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Thomas explains, “the whole overview of this collection is not so much that it’s cartoons and black — these are groundbreaking because they were all the first, and they took place from 1969 to 1979.”

From Civil Rights To Black Power

But it wasn’t easy to build the collection.

“It was really hard to find black animation; there was really no market for it,” says Thomas. “Everything was about Disney and Warner Bros. and the Looney Tunes characters, Bugs Bunny and Tweety Bird.”

Thomas and friends put the word out to various art galleries, and when curators heard about a piece that might interest her, they would let her know.

“This aspect of black popular culture, I think there is such a significant story to tell there, coming out of the 1960s civil rights movement and shifting to the 1970s black power movement,” she says, “to come into our own and to have all of these images that were not derogatory to come on the television and in the news, and children not seeing their grandmothers’ cartoons with the derogatory images, like [Little Black] Sambo that came out of the 1940s.”

Source: NPR Code Switch