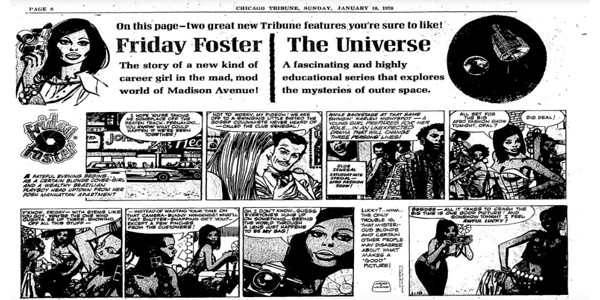

January 2015 is the 45th anniversary of first appearance of Friday Foster in a syndicated comic strip. David Moreu, a journalist from Barcelona, Spain, interviewed Jordi Longaron about his work on Friday Foster. The Museum Of UnCut Funk was contacted several months ago by David, to have our collection of Friday Foster comic strips appear in his article for the January 2015 edition of Visual Magazine. We are delighted to post the English translation of his interview.

PS check out David’s site, it’s in Spanish, but he is keeping FUNK alive in Spain!!!

JORDI LONGARÓN.

THE LEGEND OF “FRIDAY FOSTER”.

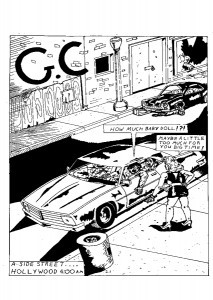

Every legend has a beginning and this cult comic strip entitled “Friday Foster” brings us back to January 18th, 1970, when it started its run in some major American newspapers in the classic format of three daily black and white panels (although on Sundays it grew to half page in full colour). Putting time in perspective, it is obvious that the adventures of this African American model turned into a high society photographer did not mean any formal revolution in the multimillion industry of syndicated strips, but as fate would have, she was the first black main character in the history of comic books and that helped to break many social taboos that crawled for decades, although some Southern outlets decided not to publish it because there was still racial segregation in the streets. Interestingly enough, a white writer from New Jersey called Jim Lawrence created those scripts with a huge Afro aesthetic and the cool drawings had the unmistakable style of Jordi Longarón, an artist from Barcelona (Spain) who enjoyed some success during the golden era of the Spanish illustrator agencies. And, by chance, he became the first Spanish comic book artist to debut in the competitive US market. Now that we are celebrating the forty-fifth anniversary of “Friday Foster,” I met with Longarón in his home studio in order to discuss the roots of this legendary work that has never been reissued, discover the personal sacrifices he underwent to keep that character alive and his thoughts on the eponymous film starring Pam Grier, which was released during the Blaxploitation days. Welcome to an exciting journey with an exceptional soul music soundtrack over the panels that changed everything without making big noise.

Let’s travel in time to the beginning of your career as an artist. Do you remember when you started drawing comic books professionally?

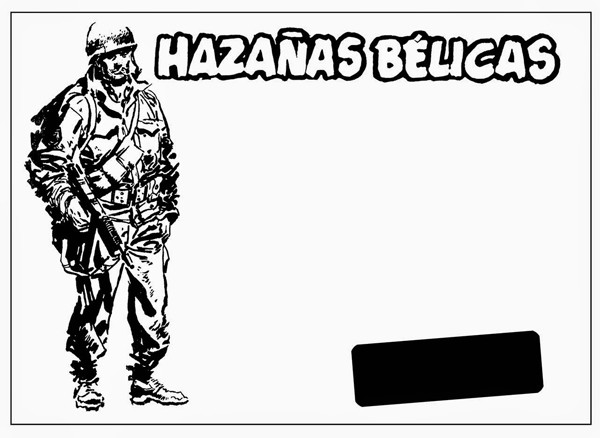

I always preferred illustration over comic books, but they appeared by chance in my life. I started working for a Spanish agency called Selecciones Ilustradas in 1956 and we made short stories for English magazines such as Valentine and Roxy, which were based on popular songs by Elvis, Tommy Steele and other singers of that era. That same year I collaborated with a French publishing company and suddenly the amount of work from abroad left us little time for local commissioning. The drawings I made for the Second World War comic book “Hazañas Bélicas” appeared in the extras that came out every two or three months and it was also in 1956 when I created the iconic soldier for the cover of the compilation albums. Despite being a self-taught artist, I managed to get some experience and you can see my progress in the job.

What was the chain of events that led you to start working on “Friday Foster” in late 1969?

Screenwriter Jim Lawrence wrote several comic books, he had a syndicated strip character named Captain Easy and was also responsible for the James Bond comic scripts published in England, that were drawn by an artist named Yaroslav Horak. It was through this work that he met Barry Coker, the agent of the Spanish agency Bardon Art based in London, and he asked him if they had any artist who could create a character with an Afro style. Barry Coker spoke to his boss Jordi Macabich in Barcelona, he contacted me and I made some samples, but then it was not even called “Friday Foster.” They sent my drawings to the writer, he showed them to the American newspapers syndicates and the Chicago Tribune News was the one most interest in publishing it.

Were you stunned about that first script, which was so different from all the stories you had drawn before?

The main character was already described as a black fashion photographer and that idea was always there. Honestly, when I made those first samples, I did not think the project would evolve and I faced it as an extra job. However, the syndicate accepted it so fast and they asked me to travel to New York City to sign the contract. So I decided to tie myself for a few years of work and see what happens.

Could you share with us any cool anecdote about that unexpected trip to New York City?

Even though Spain had a Dictatorship in those days, I had already been to England, Belgium and France, so I had experience on several trips. But crossing the Atlantic was something else. It was an adventure because I went into a completely different environment, although I was familiar with it thanks to the films I had seen in my hometown theatre. Seeing the skyscrapers was amazing and what I enjoyed the most was seeing how a big newspaper worked from inside, because the syndicate had its offices in the same building as the Daily News. I remember there were all sorts of services, including its own restaurant, where I ate the best steak of my life. Then, of course, I met the scriptwriter.

How was your relationship with Jim Lawrence once you met him in person?

Jim Lawrence and Arthur Lao, the director of the syndicate, were waiting us outside the airport doors and took us to the hotel in his Mercedes. It was the next day that we visited the newspaper offices. I became friend of the scriptwriter right away because he was a great person and he also brought me to Harlem to get documentation for the comic strip. When we left the subway station, we went to a policeman and he asked if it was dangerous to walk through the streets taking pictures. The agent recommended getting a cab and taking photos from the window to avoid major problems. I had the feeling it was poorer neighbourhood than the rest of the city, but it had a lot of life. However, there were some black people who did not seem very happy when saw me with a camera.

Were you aware of the racial segregation that was still dividing the society in the United States of America?

I used to buy many American magazines to document myself and all them featured articles on that issue. So I knew quite well what was happening there. Whether it was from films I saw, stories I read or pictures from magazines I saw, I never considered myself a foreigner while working on “Friday Foster.” I even had the feeling that I was part of that world. The weirdest thing was that the syndicate offered the comic strip to a huge number of American newspapers, but it only appeared in the Northern ones because in the South they did not accept it due to the racial issue. Some of them published it without knowing that the main character was a black woman and immediately decided to abandon it.

How do you remember the creative process of “Friday Foster”?

I draw several sketches and put them in ink, but my intention was to get away from the classic image of African Americans. I decided that Friday would have straight hair because I was inspired by a black model who had it like that and had appeared in a Playboy issue. Then I thought it was not necessary to use a very Afro style and very dark skin, though it is easy to appreciate that she is black. If you look closely, it happens the same with male characters and you notice they are black because of their looks. Being a comic strip printed in black and white, it would have been very difficult for me to make dark skin because I should have used many shades and I wanted avoid that.

Did your work and style evolve during the four long years that you were drawing the comic strip?

I had such a direct contact with Lawrence, that he always sent me the scripts by post. This also caused us some problems because of delays in the delivery and, at certain times, I needed the help of another cartoonist named Alfons Font. I do not remember if I made the pen and he made the ink or vice versa, but there was no choice because then everything was already delayed. When we started, I had to draw three months of panels in advance, but if the work was delayed for any unforeseen causes, then everything went wrong. I remember the writer often called me to explain things or tell me if he had sent any special documentation for a story.

By the way, did you face some kind of censorship during those days with the American syndicate?

They never refused anything, although they cut a small part of a panel. It was in the first story, where the male character, who is white, goes to Harlem to make a photo report, then he encounters a gang of black kids and one threatens him with a knife. That action appeared in the script that way and I draw it as it was written, but the syndicate removed the weapon and readers did not understand what was happening, because they only saw a kid with nothing in his hand.

Did you know what American readers thought about “Friday Foster”?

The American audience is different from the Spanish because they send letters to the newspaper to tell if they enjoyed or not the weekly comic strip. I remember a story, which depicted the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and I drew some panels with the facade and the interior of the building… it turned out that the museum director sent a letter saying thanks. And Tom Jones asked for an original panel because in the second episode appeared a Welsh singer and he really liked that anecdote. The syndicate sent it to him and now he has one of my drawings.

Was there continuity with the stories and the issues you addressed in the comic strip?

The episodes lasted a couple of months, even though the main characters were always the same: Friday Foster and the white photographer she worked for, as well as her young black brother who appeared occasionally. There were detective stories, some times romantic episodes and there was even one where they travelled to Granada (in the South of Spain) and flamenco dancers appeared all around. The scripts were well written because Lawrence was a great professional and he also published some novels. By the way, I’ll tell you an amazing anecdote: he explained me that when he was 18 years old he came to Spain to fight Franco during the Civil War.

So Jim Lawrence came to Spain as part of the International Brigades fighting against fascism…

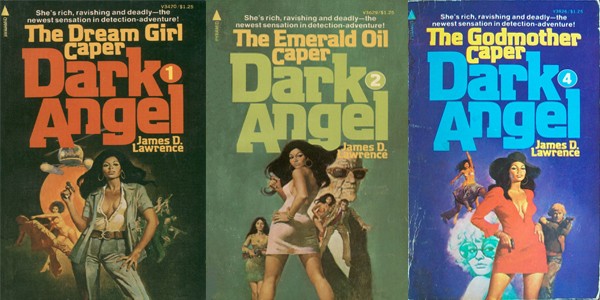

He came through France and told me that he arrived to the city of Figueras up North, but it should have been the last stages of the war and someone told him it would be better to leave because there was nothing left to do and fascists could kill him. He obeyed, even though he really wanted to fight for the Spanish Republic. That captivated me so much and it showed me the generosity of Americans. Now their image has declined a lot, partly because of politicians, however, people are different and have that sense of generosity that it is difficult to understand from my country. I kept in touch with Lawrence long after we stopped working on “Friday Foster,” we sent each other postcards for Christmas, we wrote letters quite often and he even asked me to draw the covers for a series of novels he had written about a black detective inspired by Friday. It was called “Dark Angel.”

I have read that you combined the work on “Friday Foster” with a collection of book covers for the French market…

You’re absolutely right. I combined that comic strip for America with half a dozen book covers a month for France and that was a lot. I spent four years doing virtually no holidays and enjoying no Sundays because I worked so hard to reach the deadlines. It was a very rough time for me and in early 1974 I became tired of “Friday Foster“. I am a very restless artist who likes trying new things. To make such a project, you must have a very special mentality and agree to spend several years doing the same drawings. And it did not sold as much as we expected, so I lost all interest in it.

In 1975 Pam Grier starred in the film version of “Friday Foster.” Did you have the chance to see the adaptation of your famous character in the big screen?

An American cartoonist drew the last stories of “Friday Foster,” but I do not remember his name. He only lasted a few months and then the syndicate decided to end the strip because it had lost its core audience. The film had nothing to do with my creation, but this always happens with adaptations. I really liked Pam Grier and she was so beautiful. However, the male character was too silly, when in the panels he was not that stupid. These are changes that directors make in their films and I do not have anything wrong to say about them.

Despite the lack of success and your discouragement, you kept drawing some comic books for a French publisher before you decided to retire…

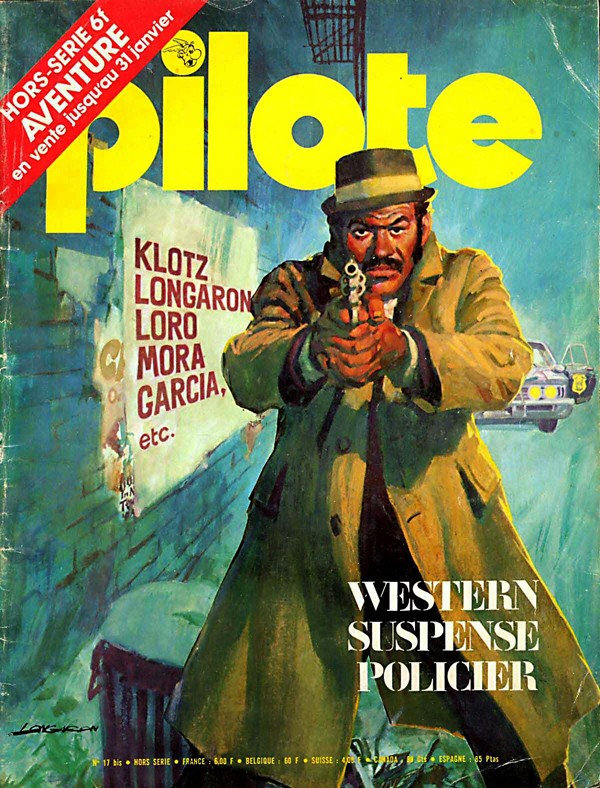

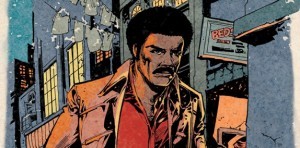

I drew one for Pilote magazine, which was written by Truchard, and the main character was a black police officer. The publishers had seen “Friday Foster” and really enjoyed that style, so they even asked me to do the cover of that issue. Then I drew a few scripts that Victor Mora had written (he was the creator of a Spanish hero called Captain Thunder) and in the 80’s I did 200 covers of fantastic and historical novels for Mondadori in Italy. Then Norma Editorial in Barcelona was interested in collecting “Friday Foster” and they talked to the syndicate in America, but the project did not work because they lost the originals and most of the panels were missing. It is a shame, but maybe they did not worry enough about the comic strip and thought people would forget about it.

2015 Copyright David Moreu

Text and photo: David Moreu (www.davidmoreu.com)

To view the Museum Of UnCut Funk’s collection of Friday Foster comic strips please visit: https://museumofuncutfunk.com/2013/01/19/the-friday-foster-chronicles/

1 Comment

Nice story. Looking at a sunday page of Friday Foster strip art drawn by Mr. Langaron on ebay right now and wanted to learn more. Boyo did I! By the way the artist that took over for him was Gray Morrow and/or Gray Morrow. My references give both. Thanks!