Josiah Howard is the author of “Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide” (now in a fourth printing). His writing credits include articles for The New York Times, Reader’s Digest, The Village Voice and Motion Picture. Here is his latest article on the use of the N Word in Hollywood.

“So we respectfully agree to disagree… ” That was Oprah Winfrey’s response to Jay Z when he appeared on her talk show in 2011. She had asked him about the validity of using the “N” word in his songs. “[Speaking] for our generation,” Jay Z assured, “we took the power out of that word… we took a word that was very ugly and hurtful and turned it into a term of endearment.”

The debate over the usefulness and/or validity of the “N” word in art remains a stickler. White people, for the most part, let the debate go on without much say: at least not publicly. People of color are divided. On the one side are the forty and older group who believe the “N” word is both disrespectful and dangerous. On the other, are those twenty five and younger, a demographic that hears the word constantly in their favorite music and films, sees it on their social network apps, and uses it casually as a “cool” affectionate acknowledgement.

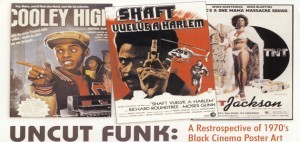

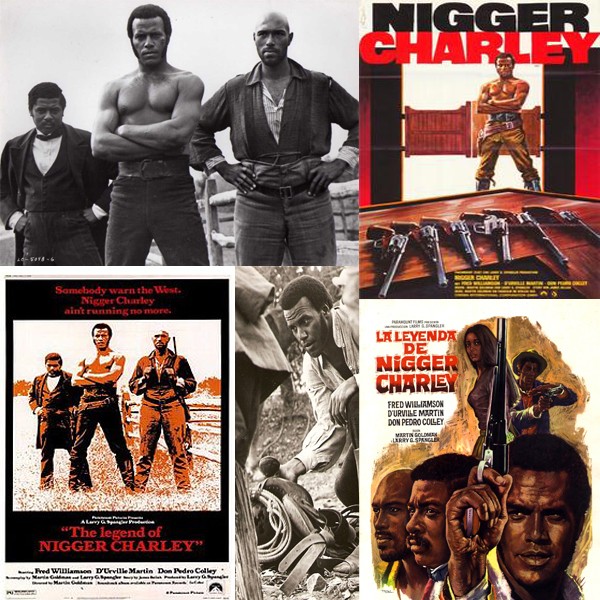

During the nineteen seventies, at the height of Hollywood’s one and only African American motion picture boom, the “N” word appeared in popular media and danced unapologetically across movie theater marquees. Blaxploitation films (black cast action-oriented films released between 1970 and 1980) provided the ubiquitous forum. Paramount Pictures’ “The Legend of Nigger Charley” (1972) was the first film to use the “N” word in an actual movie title. In conjunction with the release of the film Paramount rented a three story high billboard in New York City’s Times Square. The poster art showed a defiant African American male (athlete- turned actor Fred Williamson) staring threateningly down at onlookers. The tagline: “Somebody warn the West. Nigger Charley ain’t running no more!”

But if Nigger Charley wasn’t running, African Americans were: to the movies. Enchanted with a slew of films featuring young, militant-minded, gun-toting performers, presented, as they were, in revenge-centered blacks-against-whites fantasy scenarios, black patronage of Blaxploitation films helped Hollywood out of a fiscal crisis (in the early seventies the studios were famously on the verge of financial ruin) and sanctioned the Stateside and international use of a controversial word.

“The Soul of Nigger Charley” (1973), was Paramount’s sequel to the “The Legend of Nigger Charley.” A follow-up box office success, the film paved the way for further similarly titled entries. Box-Office International’s “Run, Nigger, Run” (re-titled “The Black Connection” for “sensitive markets”) played in theaters the same year as “The Soul of Nigger Charley.” Where Paramount’s “Nigger Charley” films enjoyed a first run in America’s A-List movie houses and was reviewed by The New York Times, “Run, Nigger, Run” dazzled audiences in the exceedingly lucrative (but underreported on) Grindhouse and Drive-In movie markets: venues in which sensational film titles were elements of a long standing business model.

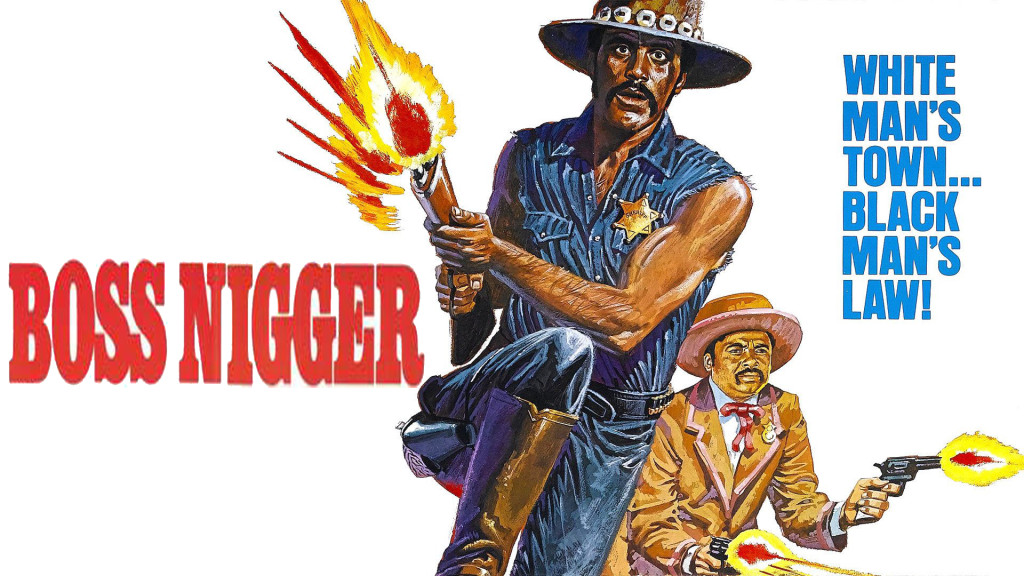

“Nigger Rich” (1974; AKA “Baby Needs a New Pair of Shoes” and “Jive Turkey”) was another contentiously titled “N” word film entry. Produced by Alert Film Releasing, Inc, the film title incorporated both the “N” word and black slang: (The Urban Dictionary: “Nigger Rich”; “spending your money unwisely on things you don’t need and won’t last that long.”) 1975’s Dimension Pictures continued the trend with “Boss Nigger” a film that also exploited the vernacular of the day. Slang for a black man who plays by his own rules—even in a white environment, “Boss Nigger” kept the door open for 1978’s “The Six Thousand Dollar Nigger” (AKA “Super Soul Brother”), International Cinema’s errant take on the popular “The Six Million Dollar Man” TV series.

So, what are we to make of Hollywood complicity in using the “N” word in movie titles? To be sure, when the pictures played in theaters, the word was omnipresent: on TV; Good Times, The Jeffersons and What’s Happening!!, on vinyl; comedian Richard Pryor used it extensively in his act and titled his best-selling album “That Nigger’s Crazy,” on Pop radio; Rickie Lee Jones (a Caucasian artist) uttered the word in her free-association hit “Chuck E’s in Love,” and, of course, in Blaxploitation and crime-centered movies.

Was Hollywood insensitive or merely shrewd—peppering movie titles with a word that pushed the parameters of acceptability but stopped just short of being wholly offensive? Or was the film capital doing what most people still do today: turn a blind eye to a potent, divisive and forever controversial word?

Paramount Pictures has never released their “Nigger Charley” films on Home Video (they’re available on bootleg label Blax Films). Dimension Pictures’ “Boss Nigger” is available, albeit under a new streamlined title: “Boss.” And “Run, Nigger, Run,” “Nigger Rich,” and “The Six Thousand Dollar Nigger,” masquerade behind their original “sensitive market” titles: “The Black Connection,” “Jive Turkey” and “Super Soul Brother,” respectively.

“Those pictures had the word ‘Nigger’ in the titles because it got people’s attention… ” surmised Fred Williamson in a 2004 television interview. Forty years after the fact they still do.

Josiah Howard

Contact: Josiahhoward.com