Daddy Cool is one of the first graphic novels the Museum Of UnCut Funk archived in it’s collection. Being a fan of Black and White comics I sought out this novel for the collection. I have found very little written about Daddy Cool. I did, however, come across one article written by Kristy Valenti for Comixology. We thank Kristy for allowing the Museum Of UnCut Funk to reprint her article.

Thanks to a small table in the back of Family, David Kramer and the Harkhams’ curatorial bookstore, I was familiar with the Los Angeles-based Holloway House, a publisher of paperback originals instrumental in the first wave of urban fiction by writers such as Iceberg Slim (Robert Beck) and Donald Goines, when I picked up the graphic-novel version of the latter’s Daddy Cool. Daddy Cool was adapted (in 1984, although it was reprinted in 2006 after Kensington acquired the rights to much of Holloway House’s backlist) by Don Glut and drawn by Alfredo P. Alcala.

Goines and Glut might be guilty of romanticizing Daddy Cool —a hit man with a code of honor who is fiercely protective of his daughter —but they don’t glamorize his life or his milieu. In fact, his problems are of the most ordinary sort: he’s estranged from his wife; he’s beginning to lose control of the behavior of his shiftless stepsons; and his daughter — a Daddy’s Girl — rebels against him under the influence of a bad boy. When his daughter, Janet, runs off with the “bad boy,” a pimp who seduces her into prostitution, Daddy Cool’s life falls apart. To mimic the “black American English” passages of Goines’ book, certain words are spelled differently — “surprise” is “surprize” — and some word balloons lack punctuation to convey staccato dialogue.

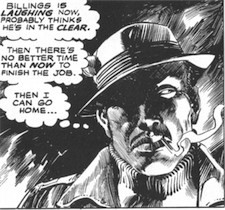

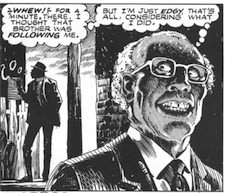

Unfortunately, in an effort to condense the novel, characters spout quite a bit of exposition, and certain sequences — such as Daddy Cool killing a barking dog while making his escape — lose their effectiveness as his logic is laboriously spelled out in thought balloons. There’s also a tension between the balloons and the narration boxes. While the thought-and-word balloons appear to be distilled from Goines, the narration boxes are much more stilted: “Daddy Cool remembers his only close friend Earl, begging him to let him handle the young disrespectful punk.” Between Glut’s adaptation and Alcala’s art, it’s easy to forget that this was an independent, not mainstream, GN — until the four-letter words, raping and killing begin.

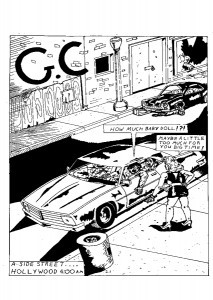

Alcala’s background in horror comics (he worked on House of Mystery and House of Secrets for DC, and for Warren’s Creepy and Eerie) is very evident in the first few pages of black-and-white, magazine-sized Daddy Cool: in the way that the lighting on a victim’s face suddenly turns chiaroscuro, in the sinister, moldy drippings in an alleyway. A few pages in, however, Alcala has mostly been able to shake the trappings of the supernatural for a grittier, more “realistic” mode.

Alcala depicts the urban settings in question — namely, Detroit and Los Angeles — in a heavily hatched style; his figure work is stiff, but it helps sell the hardboiled tone of the book (Donald Goines has been compared to Jim Thompson, and this GN is textbook noir). Visually, his characters are recognizably black, but not to the point of stereotype. (They do seem heavily photo-referenced.) Teen Janet, however, continually morphs character design. (She also manages to upset scale; at one point, a bathtub she’s in swells to the size of a Cadillac.)

Judging from the artwork, Alcala seemed most comfortable drawing fight scenes: the only real gracefulness in the book is when Daddy Cool (and later, Janet) throws knives. His six-panel page layouts keep the pacing brisk, but despite all the detail he puts into his art, it can be difficult for the reader to keep oriented: at one point, one of Daddy Cool’s stepsons materializes in a room, and at another, Daddy Cool’s assassination appears to be thwarted, because the mark has a female companion — who is shown in one panel, remarked upon, and then promptly ignored, as Daddy Cool kills the man and runs away anyway. Los Angeles looks very much like Detroit, and Detroit like Flint. I suspect that a 64-page sustained narrative must have been a challenge for an artist accustomed to working on six-and-eight page stories.

The Daddy Cool GN is also something of a literary-theory field day, as Daddy Cool, whose power is on the wane, must find someone to replace his position in the patriarchy, and his stepsons’ guns, symbolically, are no match for his knives (in the last scene with his stepsons, Buddy is too impotent to even try to grab the gun). At the end of the story, it’s Janet’s mastery of the phallic knives (though, the text is careful to point out, she is not as masterful with them as he is) that prove her to be his worthy heir in the symbolic order.

The Daddy Cool GN is a noteworthy experiment that probably serves best as a reminder of the strong relationship between pulps and comics. As such, it functions more as an enticement to learn more about Goines himself — who wrote 16 books in five years inspired by his real-life experiences as a heroine addict and frequent prisoner, and died tragically — or as an advertisement for the source material, as Daddy Cool the novel is regarded by many as Goines’ finest.

Article by Kristy Valenti. Kristy Valenti currently works for The Comics Journal.

Please click here to see our exhibition of the Daddy Cool Graphic Novel

1 Comment

Alcala did a lot of full size comics & magazines by 1984. He was doing Batman, Conan at that time. He did Planet of the Apes, and a lot more. He wasn’t dong horror by ’84. He just created He-man in ’82.