Like many other venues in 1960s America, the comics page was essentially racially segregated. The diversification of the comics required the mainstream acceptance of Charles Schulz’ Peanuts and the persistent idealism of one of its readers.

The year was 1968. The relationship between white Americans and Black Americans were all over the newspapers, except for the funny pages. You might see white folks consorting with African natives in The Phantom or Tarzan, but the aggressively racially mixed Wee Pals was only in a handful of papers, and we didn’t even have Broom-Hilda yet to show us that green folks and purple folks could live together in relative harmony.

That absence should not have surprised anyone. Progress was being made on race relations, but it was not coming quietly or smoothly. Integration was always accompanied by controversy, and controversy was not something that was courted on the comics page. Events came to a head on April 4, when an assassin took the life of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

Many saw that tragedy as a call for action, and among these was Harriet Glickman, a white schoolteacher and mother of three living in the suburbs of Los Angeles. Less than two weeks later, she wrote a letter to the most successful cartoonist of the day, Charles Schulz, suggesting that it was time to integrate that strip, noting that “the introduction of Negro children into the group of Schulz characters could happen with the minimum of impact.” Not content to seek a token appearance, she expressed the “hope that the result will be more than one black child…. Let them be as adorable as the others…but please…allow them a Lucy!”

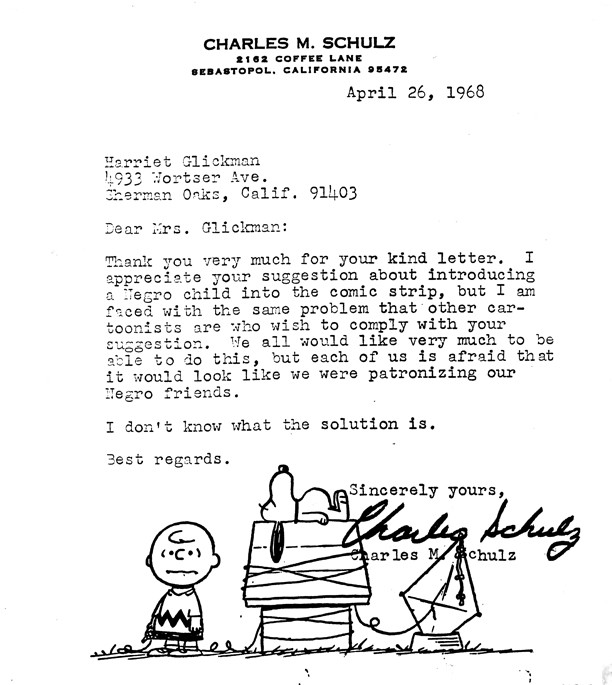

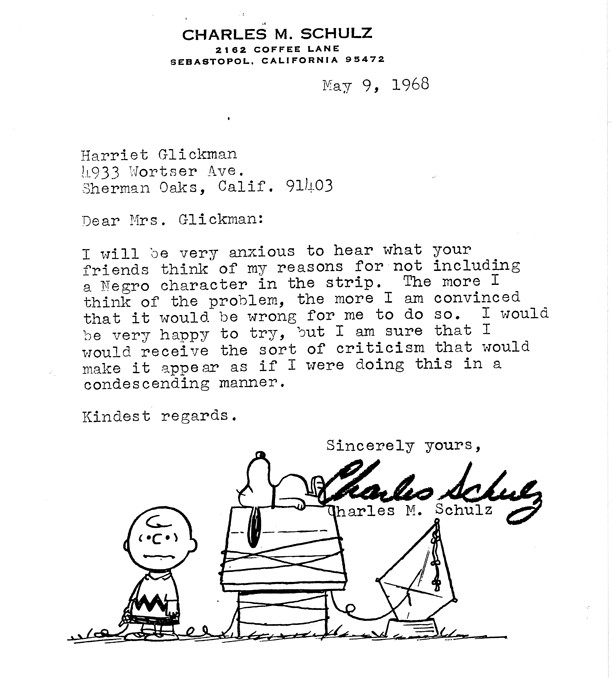

That request earned a personal reply from Schulz, who noted that such ideas had been discussed with fellow cartoonists, but that they were afraid that such character introductions would be seen as “patronizing our Negro friends.” Glickman seized on the apparent desire of Schulz to get past that point and sought his permission to run the concept past some of her own “Negro friends.” Schulz was eager to hear what their thoughts would be, but confessed that “the more I think of the problem, the more I am convinced it would be wrong to do so.” (Schulz was hardly alone in his reluctance. Glickman entered into a longer correspondence with Allen Saunders, then-writer of Mary Worth, who noted that the strip had formerly included Black characters in supporting roles, generally doing menial work but depicted with dignity. He explained to her that “it is still impossible to put a Negro in a role of high professional importance and have the reader accept it as valid. And the militant Negro will not accept any member of his race now in any of the more humble roles in which we now regularly show whites. He too would be hostile and try to eliminate our product.”)

Glickman’s efforts to collect letters from her friends (and from then Los Angeles councilman Tom Bradley, who would later become mayor) were interrupted by another assassination, the June killing of Bobby Kennedy. Glickman chose to send along the two letters she had, both suggesting that the inclusion of Black characters would not be seen as patronizing and could be a powerful effort to making calm relationships between children of different races seem normal. One letter called specifically for using Black kids as “supernumeraries”—mere background characters to fill out crowd scenes—at least until the stage could be set and the time was right to bring one such character to the fore. (The writer, one Kenneth C. Kelly, noted that Black supernumeraries were used regularly in movie prison scenes and other moments of unhappiness while seldom included in scenes of day-to-day life.)

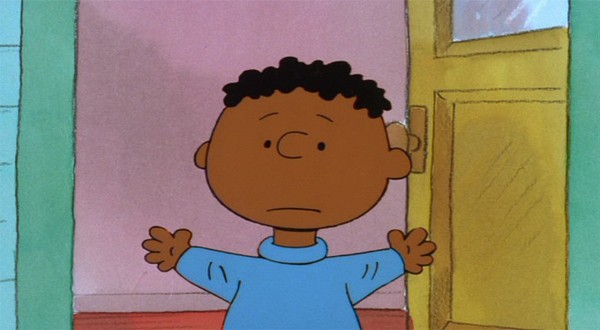

Glickman promised to send of more letters once they were completed, but she never had to do so; those two letters had won the cartoonist over. On July 1, Schulz sent her a brief note that he had taken “the first step,” which would see print during the week of July 29, and which “I think will please you.” That first step was the introduction of Franklin, a Black boy.

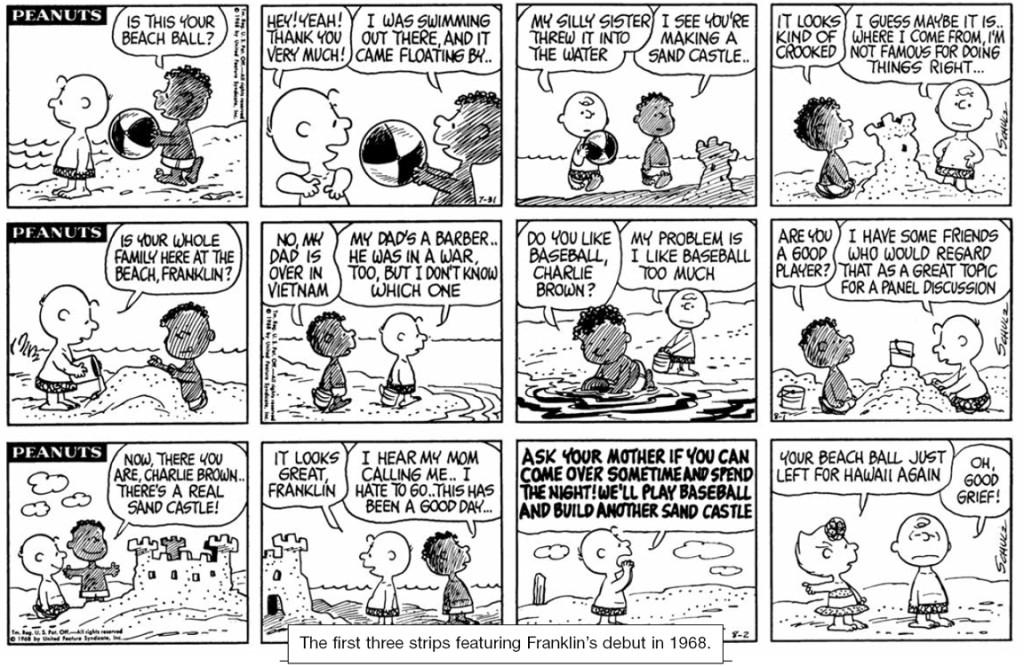

Franklin’s introduction was part of a five-day sequence featuring Sally tossing away Charlie Brown’s beach ball and Franklin rescuing it. In some ways, this seems an aggressive bit of integration—many American public beaches, while no longer legally segregated, were still de facto segregated at the time. In other ways, the strips suggest what might be seen today as an excess of caution; of the twenty panels of the series, Franklin is in ten panels and Sally is in eight, but never is Franklin in the same panel as the white girl. Franklin would not reappear for another two and a half months, when he came for a visit to Charlie Brown’s neighborhood. He was somewhat lighter skinned here, which seems to be less a matter of trying to make him acceptable to the readers and more a matter of cutting back on shading lines which were overpowering his facial features. Franklin’s job in this series was to react to the oddness of the neighborhood kids, and that was a precursor to what would be his primary role in the strip as a whole. Perhaps due to excessive caution, Franklin was never granted any of the sort of usual quirks that define a Peanuts character, the very sort of mistake that Glickman was warning about when she called for one of the Black kids to be “a Lucy.” Schulz may have had more to work with if he had listened to Bishop James P. Shannon, who had marched beside Martin Luther King in Selma; Shannon was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as wondering if the new Peanuts character would be “a believable human being who has some evident personal failing,” versus being “a perfect little Black man.” But whatever failings (or problematic lack of failings) Franklin may have had, his appearance drew national media coverage, and made local comics page editors flinch.

For years, Franklin’s real role was to sit adjacent to Peppermint Patty in class and react to her oddness; after that role was ceded to the quirkier Marcy, he was without a key role. Eventually, Schulz tapped him for scenes where he and Charlie Brown would talk about their grandfathers. In the licensing realm, he appears largely in the role of a supernumerary; while there have been occasional Franklin items produced, he’s more likely to appear in a group shot on a t-shirt or packaging for a Peanuts product, making the line-up look more inclusive. (The recent A Charlie Brown Christmas action figure line featured the first Franklin action figure ever produced, which is particularly odd when one considers that Franklin was not in that particular TV special, which first aired years before he joined the strip.)

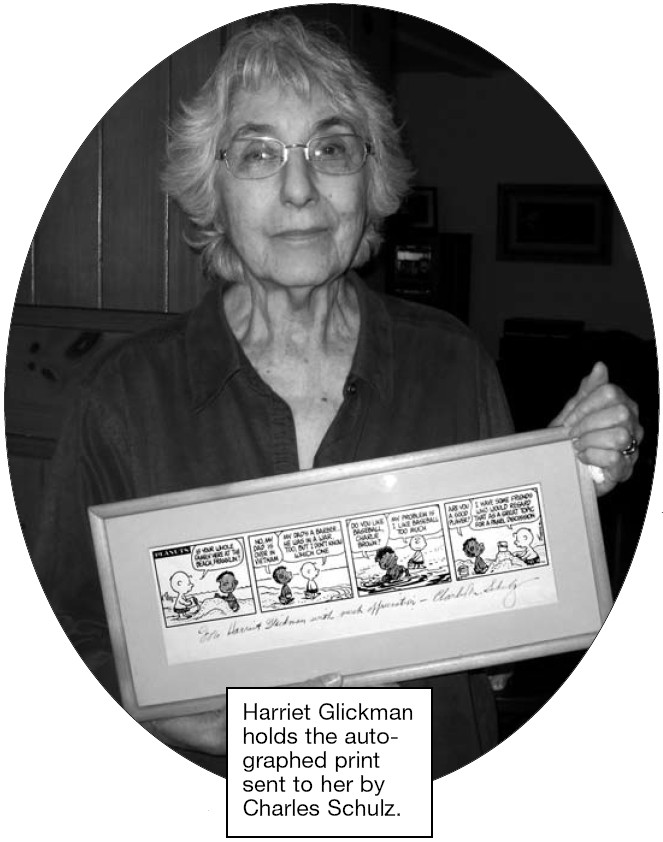

Glickman moved on to become a board member of the area’s Fair Housing Commission. She left the schoolteaching days behind and ended up working in the Southern California Association for Philanthropy. Now in her eighties, she has never left her concern for civil rights behind, nor did she leave behind Franklin, collecting what Franklin memorabilia is to be had. While the character may be blander than she might have hoped for, she is nonetheless proud. “I always refer to Franklin,” she admits, “as my fourth child.”

Source: http://cartoonician.com

Franklin © [2013] Peanuts Worldwide LLC