West Africans had been growing varieties of rice for several thousand years before the start of the slave trade with the colonies. Should Black folks get reparations for creating what is now a billion dollar plus rice industry. I say YES!!!

A significant crop produced in colonial South Carolina was rice. The production of this crop required its workers to possess knowledge of the land and rice cultivation, as well a sufficient labor force able to maintain it. Due to the omission of this crop in their European culture, English colonists who settled the rich North American land lacked the expertise required for the production of rice. Thus, the huge task of cultivating, processing, and packaging rice on South Carolina Plantations was commonly assigned to slaves. This task, though foreign to European colonists, proved to be quite common to the slaves who had been purposely imported from the rice growing region of West Africa. Where many English planters had failed in their previous attempts at growing and processing rice, the knowledge and rice-growing skills possessed by West Africans gave them a newfound success at cultivating the crop.

In addition to being knowledgeable about the process of cultivating rice, West African peoples also had the advantage of being able to easily adapt to the moist Carolina climate and landscape. This was primarily the case because the southeastern land very much resembled that of their African homeland (Wood 1974, 117). The combination of all these things made West African slaves one of the most valuable assets on South Carolina rice plantations, giving them a major role in the successful production and preparation of rice.

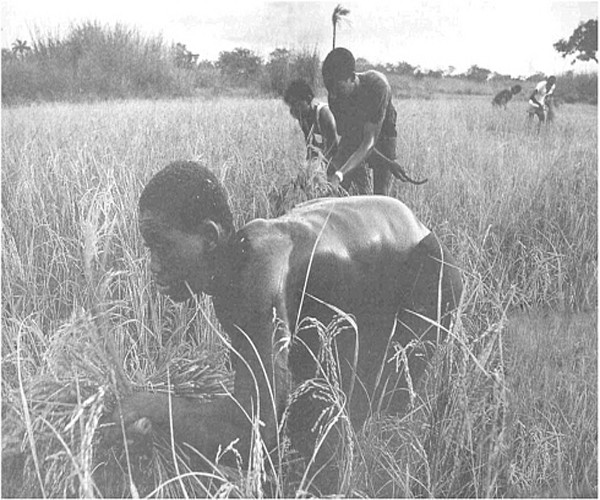

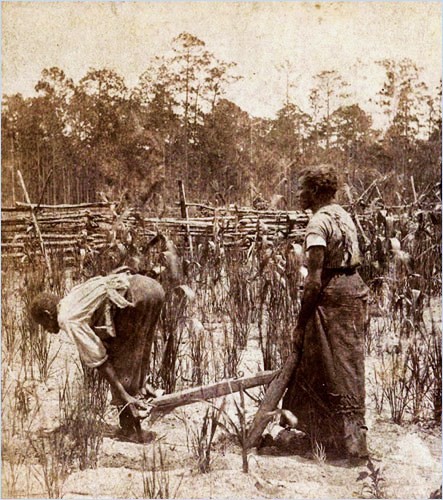

Although the benefits of rice production were many for the planters of South Carolina plantation owners, these benefits were rarely experienced by the slaves who were responsible for this success. For slaves, the process of cultivating rice was a demanding and potentially life-threatening job that forced them to work tirelessly each day to complete the necessary tasks. According to information provided by African American Heritage and Ethnography, the process of growing rice was a tedious process that began with the clearing of swamp infested lands, a job that was usually done by the male slaves. The process continued with the sowing of the rice was which conducted by the women. Rice seedlings were poured into water-soaked soil and submersed in the muddy soil using nothing but the slaves’ bare feet (African American Heritage and Ethnography 2006). The rice was then harvested, or collected from the fields and threshed. Threshing, which involved removing the rice from the hulls, involved the strenuous process of repeatedly pounding the rice using a tool uniquely created by the slaves known as a mortar and pestle. The hulls were then separated from the rice through the shifting of the hulls in a winnowing basket handmade from leaves. Once the entire process was complete, it began again with the preparation of the land for the next season’s crop.

The process of planting, harvesting, threshing and winnowing rice alone was not the only threat posed on slaves residing on South Carolina Rice plantations. As a result of the view taken by most Southern planters, slaves were often treated cruelly by their owners. As a result of working in the moist, disease-carrying waters of the rice fields, slaves often ran the risk of becoming sick, injured or even killed by animals lurking in the muddy lowlands.). Yet, even in times of sickness or injury, they were expected to report to the fields to perform the tasks that they had been assigned rarely receiving very little time to recover or recuperate. If a slave failed to complete the tasks assigned to him in the filed, they could be severely beaten or punished. These conditions made life as an African slave on a Southern rice plantation extremely difficult and, in some cases, unbearable.

In ”Black Rice,” Judith A. Carney, a professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles, finds new ”ways to give voice to the historical silences of slavery.” Exploring crops, landscapes and agricultural practices in Africa and America, she demonstrates the critical role Africans played in the creation of the system of rice production that provided the foundation of Carolina’s wealth.

In order to understand the role of Africans in rice history, Carney argues, it is necessary to think of rice as a ”knowledge system” — not just a plant or a seed but an entire complex of techniques, technology and processing skills. Africans imported as slaves into Carolina possessed this knowledge, and used their understanding to guide phases of evolution in American rice production.

Repost from US Slave Blog.

Sources: Slave Narratives. Michigan: Scholarly Press, Inc., 1976.

Negro Cabins on a Rice Plantation. Retrieved June 26, 2008, from New York Public Library, Digital Gallery.

Rice Fields. Retrieved June 26, 2008, from International Cheesehead.

Slave advertisement. Retrieved September 16, 2009, from the National Park Service.

Wood, Peter. Black Majority. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1974.

Brown, Audrey and Erica Hill (2006). African American Heritage and Ethnography: A Self-Paced Training resource. Retrieved September 16, 2009, from the National Park Service.

0 Comments