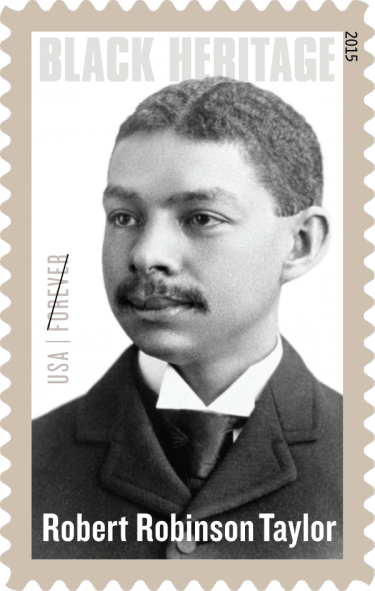

Robert Robinson Taylor, believed to have been both the first African-American graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the nation’s first academically trained black architect, became the 38th honoree inducted into the Black Heritage stamp series.

His great granddaughter, White House Senior Advisor Valerie Jarrett, joined Postmaster General Megan Brennan in dedicating the stamp.

A’Lelia Bundles, Chairman of the National Archives Foundation; Allen Kane, Director of the National Postal Museum; Bernard L. Richardson, Dean of the Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel at Howard University; L. Rafael Reif, President of MIT; Megan Brennan, Postmaster General and CEO of the U.S. Postal Service®; Valerie Jarrett, White House Senior Advisor; Brian L. Johnson, President of Tuskegee University; Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee; Eric H. Holder, Jr., Attorney General; Ronald A. Stroman, Deputy Postmaster General of the U.S. Postal Service®; Richard Kurin, Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture

Ronald A. Stroman, Deputy Postmaster General of the U.S. Postal Service®; Eric H. Holder, Jr., Attorney General; Valerie Jarrett, White House Senior Advisor; Megan Brennan, Postmaster General and CEO of the U.S. Postal Service®

Son of a Former Slave

Taylor was born June 6, 1868, in Wilmington, NC. His father was a former slave who had become a successful carpenter, contractor and merchant. From his father, Taylor learned carpentry and construction. After graduating from secondary school, he worked as a construction foreman before moving to Boston in 1888 to study in the architecture program at MIT.

Taylor’s studies were rigorous. He typically spent seven hours in class per day, and by his second year was taking as many as 10 courses per semester in such wide-ranging subjects as mechanics, acoustics, structural geology, heating, ventilation and sanitation, as well as in drawing, history, English and French. He earned honors in trigonometry, architectural history, differential calculus and applied mechanics, and was always at or near the top of his class.

Upon graduating, Taylor had several offers for teaching jobs, including an invitation from educator and activist Booker T. Washington to work at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Tuskegee, AL. Washington had founded the school in 1881 not only to help African-Americans acquire valuable practical skills, but also to show the world what an all-black institution could accomplish.

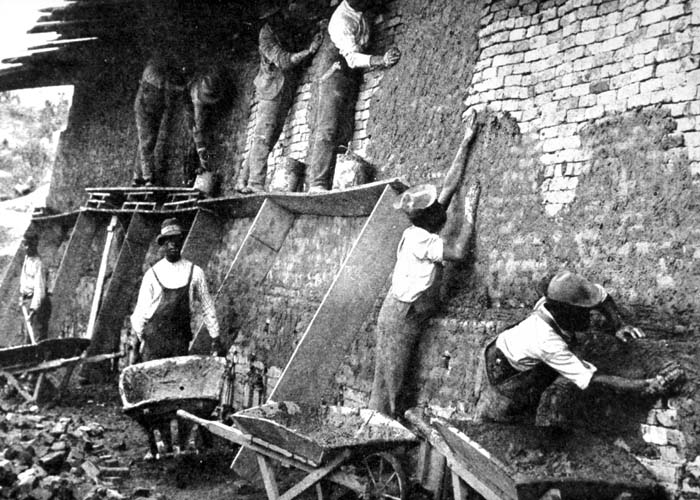

Class in mechanical drawing, Tuskegee Institute, ca. 1897

Taylor is at right. Source: Southern Letter 14 (Feb. 1897):

Developed Tuskegee’s Architectural Curriculum

When Taylor arrived at Tuskegee in 1892, he was both a beginning architect and a busy teacher of architectural and mechanical drawing to students in all industrial trades, including building construction. Before the decade was over, he had established a beginning architecture curriculum that included carpentry, cost estimation, training in drawing building plans and the study of construction problems. Tuskegee soon began offering a certificate in architectural drawing, which would help graduates enter collegiate architecture programs or win entry-level positions in architectural offices. Taylor’s efforts furthered Washington’s dream of producing not just African-American builders and carpenters, but designers and architects who planned the buildings as well.

Designer of Tuskegee’s Campus

At the same time, Taylor set about designing and building the Tuskegee campus. Upon his arrival, the school was an assortment of cottages, cabins, and simple wood-frame or brick buildings scattered across an abandoned plantation. In the years following, Taylor designed and oversaw the construction of dozens of new, state-of-the-art buildings, from libraries and dormitories to lecture halls, faculty housing, gymnasia, scientific and agricultural facilities, industrial workshops, a hospital — and, most memorably, a handsome chapel that was used for conferences, graduation ceremonies, and religious services.

Taylor’s Colonial-style designs, including half a dozen buildings with grand porticos and large classical columns, were built of richly textured, multihued bricks made by the students themselves. In keeping with Washington’s belief that well-designed community buildings proved and nurtured racial progress, Taylor typically built in a style that was also consistent with his own personality: elegant, dignified and persuasive without being showy.

Taylor left Tuskegee in 1899 to work and study new building methods in Cleveland, but continued to design buildings for the school. When he returned in 1902, he was given the title he held for the rest of his career: Director of Mechanical Industries. He continued to design new buildings and oversaw the Department of Mechanical Industries, which included 22 divisions that trained harness makers, tinsmiths, wheelwrights, tailors, plumbers, steamfitters and many other skilled artisans.

His Inspirational Words

A 1915 letter captures the calm determination that surely inspired students under Taylor’s care. “There are not a great many colored architects and engineers in the country — comparatively few — but the number is increasing and I am glad to say that because of their work they have gradually gained the confidence of the public,” Taylor wrote. “I realize that in any movement which borders on that of the pioneer, that it takes some courage and some determination, but I believe that any risk which we may take in any operation, in any business or in any occupation, we will be fully repaid when we see that more and more avenues are being opened up for colored young men and colored young women, and the best lesson that we can give them is to let them see the things which have actually been accomplished by colored men and by colored women. I believe this would be among the greatest contributions that we can make towards racial progress.”

Unfaltering Leadership

Later in his career, Taylor played such a major role at Tuskegee that he served as acting principal when the principal was traveling. When members of the Ku Klux Klan paraded on a public road through the campus in 1923, Taylor kept the peace. He allowed a student dance to proceed as scheduled, assured the press that the institute could handle any trouble, and calmly watched from his veranda as the parade passed. He soon earned a promotion to vice principal for his strong, dignified display of leadership — but continued to serve as Director of Mechanical Industries.

Later in his career, Taylor designed or co-designed buildings beyond the Tuskegee campus as well, including a combined classroom, chapel and administrative building at Selma University; a combination office, entertainment, and retail building in Birmingham, and elegant libraries in North Carolina and Texas. In 1929, presented with a particularly interesting opportunity, he traveled to Liberia to help establish the Booker T. Washington Agricultural and Industrial Institute. He helped organize the curriculum and advised on staffing, leadership, and facilities, serving as an intermediary between missionaries, businesses, and the Liberian government; he also designed plans for the campus and its first structures. The trip was covered by the African-American press, and Lincoln University in Pennsylvania awarded him an honorary doctorate for his work.

Public Service and Advocacy Following Retirement

After retiring in 1932, Taylor returned to Wilmington, NC, and spent the final decade of his life engaged in quiet but determined public service and advocacy. He promoted a federal homesteading project for African-American farmers and argued in favor of federally funded African-American recreation projects. He was elected vice chairman of the Wilmington Inter-Racial Commission, served on the board of Fayetteville State Teacher’s College, and wrote to the U.S. Civil Service Commission in 1941 to protest discrimination against African Americans in the defense industry.

Final Moments Surrounded by his Masterpiece

Taylor died Dec. 13, 1942, at the age of 74 after collapsing in a chapel during a visit to Tuskegee. According to family, moments before an aneurism struck Taylor, the famously modest man who rarely talked about his work acknowledged that the chapel was his masterpiece.

In her 2012 book about Taylor and Tuskegee, architectural historian Ellen Weiss writes that Taylor was eulogized for “his principled character, his organizational abilities, his special tact on interracial matters, and his achievements as an educator and architect.” Colleagues and friends recalled him as eloquent, intelligent, dignified and kind.

MIT’s Influence

In a talk he gave on the occasion of MIT’s 50th anniversary in 1911, Taylor summarized what his MIT training helped bring to Tuskegee. In the process, he encapsulated both his personal strengths and his lasting legacy: “the love of doing things correctly, of putting logical ways of thinking into the humblest task, of studying surrounding conditions, of soil, of climate, of materials and of using them to the best advantage in contributing to build up the immediate community in which the persons live, and in this way increasing the power and grandeur of the nation.”

Source: Tuskegee University Archives MIT Museum and USPS