When 23rd president Benjamin Harrison and his wife, Caroline, fired their French chef and hired Dolly Johnson, a free black woman who had worked for them in Indianapolis, the move made national headlines. This is in jarring contrast with the recent headlines we’ve seen asking, “Where are all of the black chefs?” Then, as now, they were there doing their thing, hiding in plain sight. — Chef Adrian Miller. Photo Credit Library of Congress: Dolly Johnson, the White House cook for president Benjamin Harrison.

It is a well-known, although not so frequently discussed, fact that African-American cooks, chefs, and food writers have played a crucial and central role in the development of US cuisines since colonial times. Unfortunately, their contributions are often overlooked because of enduring social and cultural dynamics that tend to ignore their presence, let alone their unique influence on American foodways.

It is a well-known, although not so frequently discussed, fact that African-American cooks, chefs, and food writers have played a crucial and central role in the development of US cuisines since colonial times. Unfortunately, their contributions are often overlooked because of enduring social and cultural dynamics that tend to ignore their presence, let alone their unique influence on American foodways.

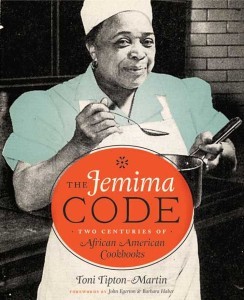

Toni Tipton-Martin does a great job of setting the record straight with her book The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African-American Cookbooks. A Californian and former food writer for the Los Angeles Times, she started collecting cookbooks by African American authors when she realized that she was, as many others, a victim of the “Jemima Code.” In her own words, “historically, the Jemima code was an arrangement of words and images synchronized to classify the character and life’s work of our nation’s black cooks as insignificant. The encoded message assumes that black chefs, cooks, and cookbook authors – by virtue of their race and gender – are simply born with good kitchen instincts, diminished knowledge, skills and abilities involved in their work, and portrays them as passive and ignorant laborers incapable of creative culinary artistry.”

Tipton-Martin’s argument and motivations could not be clearer. In her book she classifies, introduces, explains, and puts into context many African-American cookbooks from the last hundred and fifty years or so, often illustrating the text with images and pages from the original works she discusses. She not only offers her own interpretations, but also allows readers to get a sense of the language, the style, as well as the visual and material worlds that the African-American authors of the past inhabited. Above all, Tipton-Martin demonstrates how these men and women were not victims, but expressed their own personality and agency in their work, striving to be accomplished cooks or maître d’s.

This was also the case when, especially for the oldest works, the authors were not literate and had to rely on someone else’s writing skills. Yet, this did not make their knowledge, expertise, and professionalism less admirable. Works were, instead, based on an oral culture that was transmitted within their communities and families for generations, especially when African Americans were barred from reading and writing. Many of the authors featured in the book were teachers, instructors, and educators, and even the most humble cooks had learned from previous generations and were eager to pass on their knowledge.

This was also the case when, especially for the oldest works, the authors were not literate and had to rely on someone else’s writing skills. Yet, this did not make their knowledge, expertise, and professionalism less admirable. Works were, instead, based on an oral culture that was transmitted within their communities and families for generations, especially when African Americans were barred from reading and writing. Many of the authors featured in the book were teachers, instructors, and educators, and even the most humble cooks had learned from previous generations and were eager to pass on their knowledge.

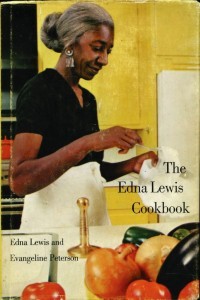

Tipton-Martin divides her material in distinct periods that go from the late nineteenth century to contemporary times. For each period, she provides thoughtful information about the situation of African-American food professionals, the overall state of African-American traditions, and how their knowledge was transmitted and interpreted within their own communities and among other readers. Her scope moves from butlers and entrepreneurs to civil rights activists, soul food interpreters and, later, celebrities like Edna Lewis.