Of the 100,000+ recipe collections published over hundreds of years of American history through the end of the 20th century, only 200 or so have been credited to black cooks and writers.

It’s a stark fact that opens The Jemima Code, which you could describe as a history book about cookbooks, by Toni Tipton-Martin. It’s an overview of 150 books, many rare, the vast majority out of print, that were written and sometimes even published by slaves and other black authors—work that was often attributed with varying-to-nonexistent degrees of credit.

It’s a stark fact that opens The Jemima Code, which you could describe as a history book about cookbooks, by Toni Tipton-Martin. It’s an overview of 150 books, many rare, the vast majority out of print, that were written and sometimes even published by slaves and other black authors—work that was often attributed with varying-to-nonexistent degrees of credit.

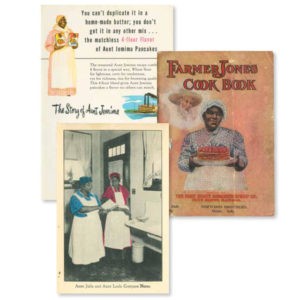

The title comes of the book comes from Aunt Jemima herself. “Aunt Jemima materialized in the 1880s, a product of commercial advertising inspired by the comic blackface routines of white vaudeville actors,” explains John Eggerton in the book’s forward. “As black women grew more self-assured and instrumental in the culinary arts of the post-bellum South, their white mistresses and masters had to find an explanation for this anomaly; in a culture that considered all blacks to be inferior, there was no room for exceptional intelligence and skill. They needed a female counterpart to the loyal and compliant Uncle Tom—a mythic persona, a caricature for all seasons.”

What arose was Aunt Jemima—first played by a 59-year-old former slave named Nancy Green at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. A warm, grandmotherly housekeeper for sure, but also one whose virtues were presented in a non-threatening way. Her figure was asexual. Her disposition was constant joy. Her background was uneducated. And her cooking wasn’t born from talent, study, or creativity, but a sort of mystical dumb southern luck, Tipton-Martin explains.

“The Aunt Jemima advertising trademark…provided a shorthand translation for a subtle message that went something like this: ‘If slaves can cook, you can too,’ or ‘Buy this flour and you’ll cook with the same black magic that Jemima put into her pancakes.’” Tipton-Martin writes in the book. “In short: a sham.”

“The Aunt Jemima advertising trademark…provided a shorthand translation for a subtle message that went something like this: ‘If slaves can cook, you can too,’ or ‘Buy this flour and you’ll cook with the same black magic that Jemima put into her pancakes.’” Tipton-Martin writes in the book. “In short: a sham.”

As you flip through excerpts of the 150 cookbooks featured in The Jemima Code, it’s more than a little depressing to see this mammy figure played out over and over on book covers which, otherwise, contain thoughtful recipes and methodologies developed by authors who are, in essence, forced to reinforce these stereotypes. To make matters worse, female slaves rarely lived much beyond the age of 33—a fact that only makes these caricature-laden covers a larger lie.

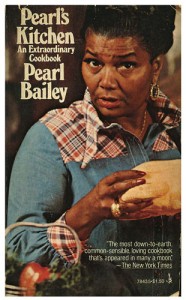

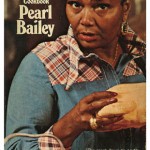

But the imagery evolves over time. And by the 1970s, the Black Power movement had swung the pendulum. On the cover of Pearl’s Kitchen, circa 1973, Tony Award-winner Pearl Bailey stares through the fourth wall right into your eyes. Her jewelry and hair both shine in an intense, strong feminine moment, and it will take you a few moments to realize: She’s actually been clasping a raw chicken the whole time.

As a retrospective, the book’s succinct overview of a very wide topic makes it a fantastic reference manual, but you, like I, may find yourself constantly teased by the brief scans of cookbooks gone, wanting to open each up to pore over the recipes of our earliest American chefs who defined the regional cuisine that our country is most known for: Southern and Creole cooking.

Luckily, there may be an answer to that impulse. Because to follow up The Jemima Code, Tipton-Martin is penning her own cookbook based upon these historic recipes. So even if our history will always look the wrong way, at least it will taste right.

Source: Fast Co Design

1 Comment

Just discovered your site, absolutely love it. The cookbook post is especially eye-opening! Great site! Check out mine at http://heroictimes.WordPress.com