1970’s Afro Styling Makes A Comeback

Towards the end of the 1970’s the Afro faded out, giving way to the jheri curl and perms. But now the ‘fro is back with a vengeance!!!“Afro picks afro chicks

I let my soul flow by my afro-d**k

Rabbit out the hat pulln afro-tricks

Afro-american afro-thick”

Ludacris, Southern Hospitality The Chours

During the late sixties, fashions changed with the times, reflecting the independence and identity of a young generation determined to break free from their parents’ values and mores. One reflection of this trend was the Afro, a natural hairstyle worn by Blacks that reflected the growing political and cultural progressiveness and self-esteem among Black people during the 1960’s.

The Afro, also known as the natural, became more than a hairstyle or fashion trend but a political statement that allowed Black people to express their cultural and historical identity. The hairstyle emerged out of the Black Power movement, which rejected Dr. King’s emphasis on non-violence as a form of political struggle. The Black Power Movement, both politically and culturally, offered Black people expression that moved away from the subservience of their forebears.

The Afro, also known as the natural, became more than a hairstyle or fashion trend but a political statement that allowed Black people to express their cultural and historical identity. The hairstyle emerged out of the Black Power movement, which rejected Dr. King’s emphasis on non-violence as a form of political struggle. The Black Power Movement, both politically and culturally, offered Black people expression that moved away from the subservience of their forebears.

Natural hairstyles were considered ugly or offensive and therefore Black people would process or conk their hair to attain a texture that was similar to or mimicked white hair. Wigs were also popular among Black women. Only members of the Nation of Islam rejected processing and straightening, believing that to do so was to embrace notions of white superiority and that the natural attributes of Black people were unattractive. Yet even the Muslims wore their hair in short and neat hairstyles. But by the late sixties, as the civil rights movement and political protests had given way to the Black Power Movement, young Blacks stopped processing their hair and allowed it to grow out naturally, affecting a halo-shaped hairstyle which was dubbed the Afro.

In the beginning, the Afro was not popular in the Black community, particularly among older Black people who were still driven by older values that the young people were rejecting.

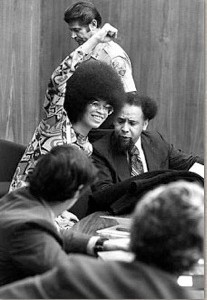

By the end of the decade the hairstyle grew more prominent as people such as Stokely Carmichael and members of the Black Panthers began wearing the hairstyle. Women, such as Angela Davis, whose Afro was a famous image of the late sixties and early seventies, let their hair grow out as well, fashioning them in large naturals or in Afro puffs, two ponytails tied together by ribbons.

But one person who would make the Afro more acceptable was James Brown. Throughout most of Brown’s early career he conked his hair, but by the time he recorded “(Say It Loud) I’m Black and I’m Proud,” Brown let his hair grow out naturally as a statement of Black pride and self-sufficiency. His song and the Afro came to define Black America during the 1960’s and became a political and cultural statement.

Source: Cynthia C. Scott

Afro Sheen

Shaft wore one, and so did Angela Davis, and as Black Pride took to the streets, Blacks not only reclaimed an affection for African dress and accessories, but many stopped processing and relaxing their hair in an attempt to conform to white standards of beauty. They shouted ‘Black is Beautiful’ and let the natural kinky state grow into a hair halo called the afro.

The afro made its first stand as racial rebellion in the 1950’s. Malcom X preached about the ‘whitening’ of Black hair by having it chemically relaxed and tamed. Followers of the militant leader agreed, growing out their afros as a slight to ‘whitey.’ The Blackstone Rangers, a Black street gang, cultivated the ‘ranger bush’: a tall, compact afro which helped soften the blows received to the head from police billy clubs. The idea was that the solidarity of the African people in a western dominated world helped to protect blacks against brutality, whether physical or psychological. And the afro was the crowning glory of the fight.

The afro made its first stand as racial rebellion in the 1950’s. Malcom X preached about the ‘whitening’ of Black hair by having it chemically relaxed and tamed. Followers of the militant leader agreed, growing out their afros as a slight to ‘whitey.’ The Blackstone Rangers, a Black street gang, cultivated the ‘ranger bush’: a tall, compact afro which helped soften the blows received to the head from police billy clubs. The idea was that the solidarity of the African people in a western dominated world helped to protect blacks against brutality, whether physical or psychological. And the afro was the crowning glory of the fight.

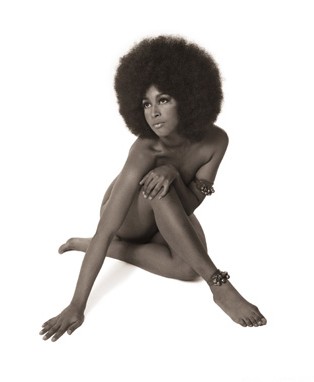

During the racially expressive 1960’s, the afro moved from militant mane to counterculture coif. Hippies opened their arms to their fellow man, and whites with naturally curly and kinky hair cultivated their own fros in a show of racial harmony. Marsha Hunt’s glorious afro turned her into the poster girl for the musical Hair, and her afro became as symbolic of the 1960’s as the peace sign.

During the racially expressive 1960’s, the afro moved from militant mane to counterculture coif. Hippies opened their arms to their fellow man, and whites with naturally curly and kinky hair cultivated their own fros in a show of racial harmony. Marsha Hunt’s glorious afro turned her into the poster girl for the musical Hair, and her afro became as symbolic of the 1960’s as the peace sign.

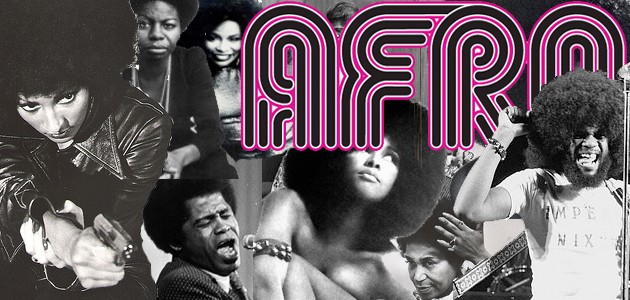

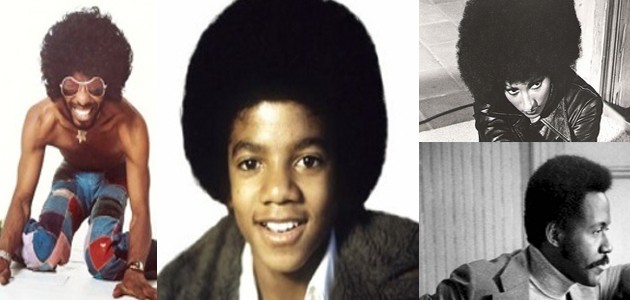

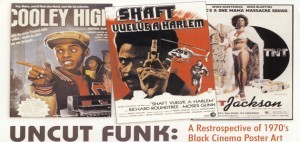

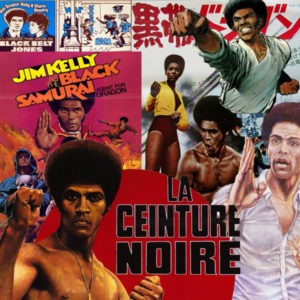

The ghetto fascination of the 1970’s brought the afro mainstream. Funk all-stars Sly and the Family Stone sported wicked fros with bedazzled jumpsuits and platform boots, inspiring Blacks and whites to get their groove on. Michael Jackson’s afro jived from the early days of the Jackson 5 until his Off the Wall album of 1982 (Michael would then propel another hair trend with his relaxed jheri curl). Blaxploitation films hustled the afro from symbol of Black pride to symbol of Black power. Richard Roundtree’s superfly fro in Shaft and Pam Grier’s foxy fro in Coffy proved that you could look fresh and still fight evil!

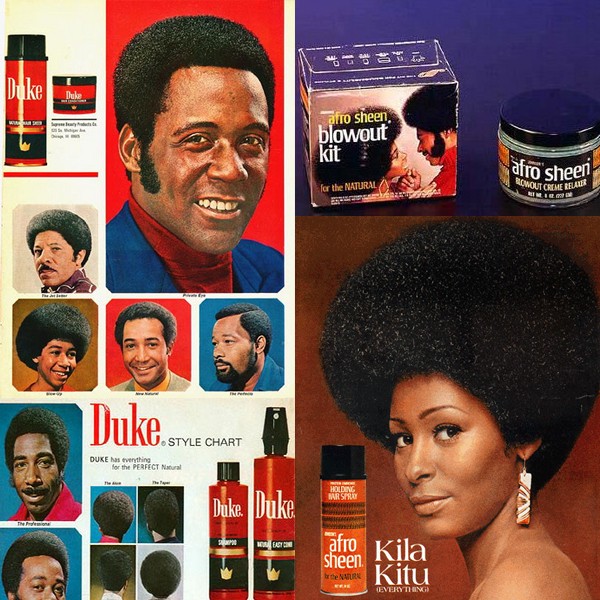

A true afro was much more than letting the hair grow in a carefree style like the straight and uncut hippie look. An afro needed meticulous care to create the balance of a perfectly symmetrical ‘fro.’ Careful afro tending included a liberal spraying of glossy Afro Sheen and meticulous raking with a big hair pick, or Afro rake, that resided permanently in the back pocket of flared leg jeans.

Afros could be cropped-close to the head or grown to such wide dimensions that it was hard to get through the door. Whatever the size, having a perfectly symmetrical crown of glory was the ultimate.

Source: Retro Nostalgic.com, Traces of a Stream.com

A Defining Afro Moment: Melba Tolliver, the first Black anchor in NYC, got the assignment of the year in 1971

President Nixon’s daughter, Trisha, was marrying Eddie Cox, and Tolliver was to go to Washington D.C. to cover the presidential event. Reporting for WABC in New York, at the time it was unusual for a local station to send a reporter out of town on a national story. However, television news was learning that ratings increased with coverage of such spectaculars. WABC, too, had reached number one ratings in the market and had done so by creating news personalities, reporters and anchors that audiences would grow to love and trust. Perhaps it was the beginning of entertaining news. The station took great pains to make sure the staff was ethnically diverse. Tolliver, Black and Geraldo Rivera, Puerto Rican, were some of the “identifiable ethnics” on staff.

President Nixon’s daughter, Trisha, was marrying Eddie Cox, and Tolliver was to go to Washington D.C. to cover the presidential event. Reporting for WABC in New York, at the time it was unusual for a local station to send a reporter out of town on a national story. However, television news was learning that ratings increased with coverage of such spectaculars. WABC, too, had reached number one ratings in the market and had done so by creating news personalities, reporters and anchors that audiences would grow to love and trust. Perhaps it was the beginning of entertaining news. The station took great pains to make sure the staff was ethnically diverse. Tolliver, Black and Geraldo Rivera, Puerto Rican, were some of the “identifiable ethnics” on staff.

Tolliver had been thinking for some time of changing her hairstyle. She was tired of processing her hair, and using wigs. So she decided to go natural, and made the switch the week of her assignment to Washington D.C. It was a modest afro, carrying little of the bold statement of say an Angela Davis afro.

“It looked wonderful,” recalls Tolliver. “People were on game shows with naturals. Cicely Tyson was on with it. Everybody was wearing them.” So she expected little opposition.

The day she switched to a natural, she was assigned to cover a dinner in Midtown. Her colleagues were shocked. Some on the crew said to her in noncommittal tones, “Oh, you changed your hair.” By the time she got back to the office, everyone on staff knew what she had done. One producer saw her and asked, “What did you do to your hair.”

Tolliver replied, “This is what my hair is like. Now I’m not going to straighten it any more.”

The news director had heard too, and he was on the phone as soon as she finished the evening news. “I hate your hair,” he said. “You’ve got to change it. And you know what, you no longer look feminine.”

The news director had heard too, and he was on the phone as soon as she finished the evening news. “I hate your hair,” he said. “You’ve got to change it. And you know what, you no longer look feminine.”

Management threatened to keep her off the air if she didn’t change her hair back. She went to Washington D.C. for the wedding, covered it the only way she knew how using live shots of herself, and let New York decide what to do with the footage.

When she returned, management was insistent that she had to straighten her hair or she’d have to wear a hat or scarf if she wanted to get back on air. Now the New York Post had gotten wind that something was happening at the station, and people were beginning to wonder why they hadn’t seen Tolliver on air. When the Post began calling people at the station, including the news director, the station backed down and put her on the air. But by now word had gotten out what had happened. It was bad publicity for the station. People wrote letters supporting Tolliver’s right to wear her hair as she pleased, even if no one liked it.

It was a defining moment in television history as Blacks grappled with how to define themselves. The struggle spilled over into other realms of journalism, but Tolliver insists this was not the defining moment of her career.

Tolliver, who was born in Rome, Ga., and raised in Akron, Ohio, started out as a registered nurse. Later she decided to give up that profession for a job that suited her perky personality. In 1966 she found a position as a clerk for a network news executive with ABC. A year later, when the on-air employees went on strike, her boss asked her if she’d be willing to try anchoring a 5-minute news show called “News With a Women’s Touch.” Tolliver performed so well, she was asked to continue to fill in for the duration of the week-long strike. Tolliver loved the experienced and thought maybe she would have an opportunity to do it again, but because she had crossed the picket line, she was labeled a scab. The union leader told her she’d never get into the union.

But time proved him wrong. After getting in-house training at ABC and taking a few classes at Columbia University and New York University, she won some confidence. She got her first break with the assassination of Bobby Kennedy. WABC the local station asked her to help out with coverage of the funeral that was scheduled at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Through the years of reporting and hosting public affairs shows at WABC, she learned the power of television news and harnessed that power to more accurately portray the varied lives of Blacks.

Source: The Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education.

Time Magazine

Monday, October 25, 1971

From the time that it first appeared on the scene five years ago, the “natural” or Afro hair style closely paralleled the growth of Black pride. Becoming a political statement and a symbol of racial identity as much as a popular hair style, it gradually billowed from close-cropped cuts into dramatic, spherical clouds that framed the heads of both women and men. Now that Blacks feel more secure about their identity and are achieving some of their political goals, the popularity of the Afro has begun to wane. Though the style is still much in evidence, it is already passé with many Black fashion leaders.

From the time that it first appeared on the scene five years ago, the “natural” or Afro hair style closely paralleled the growth of Black pride. Becoming a political statement and a symbol of racial identity as much as a popular hair style, it gradually billowed from close-cropped cuts into dramatic, spherical clouds that framed the heads of both women and men. Now that Blacks feel more secure about their identity and are achieving some of their political goals, the popularity of the Afro has begun to wane. Though the style is still much in evidence, it is already passé with many Black fashion leaders.

Says Walter Fountaine, a New York City hairdresser: “Afros are as out of date as plantation bandannas.”

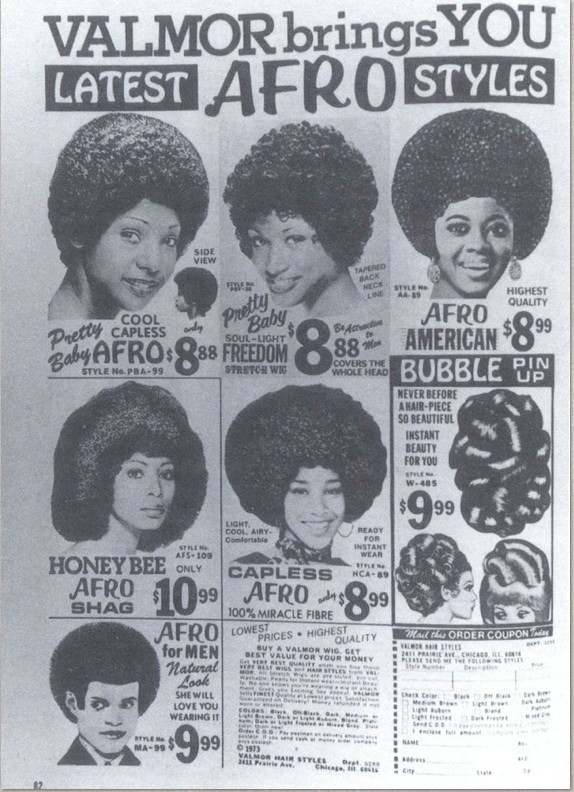

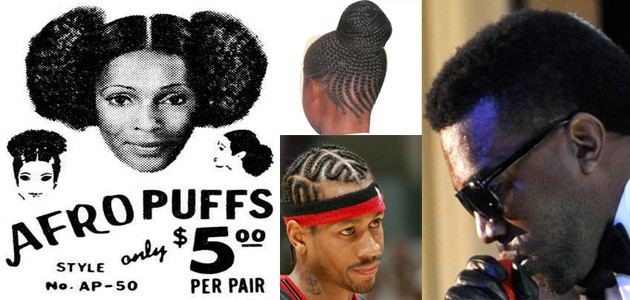

While that view is overstated, many Black men who adopted Afros have begun returning to shorter cuts. It is the women, though, who are abandoning the Afro in rapidly increasing numbers and turning to a variety of new hair styles — and a couple of old standbys. Among the most popular of the newcomers:

THE PUFF, created by parting the hair in the middle, combing it flat on top and fluffing it into two large Afro snowballs on the sides.

THE AFRO-SHAG, a short Afro with straightened hair descending along the neck and into sideburns.

THE AFRO-BRAID, a short Afro combined with a layer of small braids in the front.

THE CORNROW, fashioned by parting and braiding sectors of hair to form geometric patterns on the head.

THE BIRD, medium-length hair that is straightened and then set in large, soft curls.

In addition, both straightened hair and the Buckwheat (small braids tied with ribbons) are regaining some of their old popularity.

The decline of the Afro will be greeted with relief by many Blacks who know only too well that the look was anything but “natural.” To maintain the Afro’s cotton-candy structure themselves, they had to spend long hours in front of their mirrors using special combs and applying conditioners and sprays. For the women having it styled in a beauty parlor, the Afro was more costly than other styles. The continuous combing required to keep an Afro fluffy also caused hair to become more brittle and to break along the hairline and on the crown. Finally, the massive look of the Afro was not flattering to all faces and head shapes.

“Afros are beautiful,” says Dolores Martin, a Playboy Bunny, “but they’re like hot pants. Some people can wear them, but others can’t.” Ruth Ginyard, a Los Angeles boutique owner, agrees.

“Afros are beautiful,” says Dolores Martin, a Playboy Bunny, “but they’re like hot pants. Some people can wear them, but others can’t.” Ruth Ginyard, a Los Angeles boutique owner, agrees.

“I have large eyes,” she says, “and the Afro gave me a crazy look.”

Whatever its drawbacks and inconveniences, however, the Afro has served the Black woman well, reinforcing her ego, emphasizing her new “Black is beautiful” philosophy and preparing the way for the bold hair styles that she is now adopting. That new outlook is succinctly—and bluntly—expressed by Barbara Walden, whose line of cosmetics for Blacks is marketed across the nation: “Before the Afro the Black woman was always embarrassed about her kinked-up hair. Wearing the Afro has helped to achieve a freer feeling about herself.”

1 Comment

hello thanks for this archival footage. It really help me share my story of the era of history of the black community that makes me happy.