Whether Americans like it or not, cartoons of the 30s and 40s, considered the Golden Age of Animation, were extremely racist. Cartoons made by Warner Brothers, Metro Goldwyn Mayor, Walter Lantz, and other animation studios, depicted ridiculous stereotypes of Blacks with disquieting regularity.

It cannot be denied that the cartoons that so many enjoy to this day contained images that are by today’s standards completely unacceptable were they to be created now. One cannot see the images on television because they have been cut out, rendering the cartoons more suitable for children but it is easy to see where the censor’s hand has been when watching the cleaned up versions. Every time something explodes in a cartoon character’s face the character becomes a racial stereotype. Those myriad sight gags are no longer visible but the very choppiness is indicative of how prevalent these images were. Therefore it is ludicrous for a true lover of old animation to disassociate the unfortunate images with the rest of any given cartoon. The racism is intrinsic to the cartoon.

However, too many authors writing on the subject of animation would just as well not have to deal with the question at all. Take for example Tex Avery King of Cartoons, Joe Adamson’s book about Tex Avery who was simultaneously one of the greatest figures in animation history and one of the biggest offenders when it came to racial stereotypes. The only reference to race is in a description of the cartoon “Uncle Tom’s Cabana”: “Uncle Tom is a grand old black man (not so much a caricature as a parody of a caricature)” . And if the interview with Avery is to be believed, the main issue that modern audiences took him to task for was the violence in his cartoons!

Do we become apologists and downplay the images or languidly claim that they are not racist at all? Do we demonize them and grimly claim that there is no excuse for them whatsoever? It is not necessary to condone racism in order to acknowledge and study it in entertainment dating back to the 40s. Bugs Bunny can still be a celebrated character emblazoned on t-shirts even if we admit that he put on blackface. Rather than shy away from unpleasantness, it is far more fruitful to delve into the racism and how it relates to our collective history. Why was it acceptable at the time? How did it evolve? What does it reflect about the times in which the cartoons were made? What were the animators thinking? How did black people at the time feel about the stereotypes? And why did the stereotypes start to become unacceptable before the advent of the civil rights movement? Any animated cartoon is a reflection of its time and, when viewed as such, is an informative historical document.

The racism in animated cartoons originated in large part with newspaper comic strips from the turn of the twentieth century. The typical depiction of a black person is similar across both media and the pioneers of early animation were frequently comic strip artists to begin with. What is more, newspaper moguls regarded those cartoons of the Silent Era as ways to promote the comic strips and hence sell more newspapers. Therefore, cartoon characters appeared both in the print and movie media. A prime example is Winsor McCay and his comic strip “Little Nemo,” created in 1905, which became an animated cartoon “Little Nemo in Slumberland” in 1911. A character common to both works is Impy, a grass skirt-wearing cannibal who utters gibberish such as “google-greegle-gimpleg-bumble.” (Sampson 1). Black cannibals would appear over and over again in cartoons. Other highly influential men who made the transition from comic strip to animation were Pat Sullivan, Walter Lantz, John Randolph Bray, and Paul Terry.

Were these men racist? Probably no more than the average person at the time. It would be more accurate to say that they took the easiest road in expressing themselves. In Dark Laughter, the Satiric Art of Oliver W. Harrington, a 1993 book about a black comic strip artist, coauthor M. Thomas Inge notes in the introduction:

Throughout the history of comics, the artists were given to drawing racial stereotypes, whether the characters were Irish, Jewish, Asian, Italian, or African American. For visual humor to be effective, as in editorial cartoons or comic strips, it tends to reduce the target of the satire or joke to a recognizable, generic image, which in turn unfortunately can become a negative stereotype (Sampson 1).

So while animation helped perpetuate negative stereotypes, it by no means originated it. American racism is as old as American history, in which slavery plays a major role. One of the recurring racial themes in animated cartoons began with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s immensely popular book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a catalyst for the Abolitionist movement. Early filmmakers loved to use this story:

It’s not hard to understand why early moviemakers were attracted to it. Besides the book’s continuing popularity with readers, the fact that just about everyone already knew the characters and the plot made it an easier story to “tell” through the essentially wordless medium of silent movies. And the large number of “Tom shows” still performing the novel on stage or in tents meant that movie makers had a reservoir of trained actors, made sets and sewn costumes ready to hand. It was an easy movie for them to make, and for audiences, still learning the conventions of the new medium, to appreciate (IATH).

Naturally, the makers of animated cartoons followed suit but they did so in farcical fashion, blunting any subtleties and exaggerating certain traits. “Uncle Tom” has become a pejorative phrase, connoting a kowtowing subservient black man and the Uncle Toms in animation fit the description. In a way that today’s minds would see as grossly insensitive, cartoon makers added anachronistic gags. For example, in a 1937 cartoon, “Uncle Tom’s Bungalow,” Uncle Tom, cowering under Simon Legree’s whip says, “My body may belong to you, but my soul belongs to Warner Brothers.” At the end of the cartoon he is able to buy his freedom because of his lucky dice. As usual, it is simplistic to decry the cartoon makers as racist when they were taking a well-known story and turning it into a squash and stretch cartoon. Uncle Tom was such a standard theme that a 1944 Terrytoon cartoon, “Eliza on the Ice,” is almost identical to the former cartoon, even with Eliza running from the dogs as if the scene were a horserace. The main difference between the two cartoons is that in the latter, Mighty Mouse saves the day.

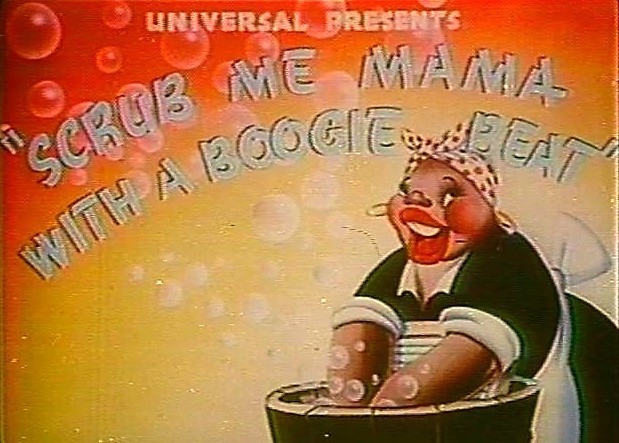

Another recurrent image takes its cue from vaudeville and minstrel shows. Mickey Mouse made his first appearance wearing tattered pants, a feature of the vaudeville costume (Klein 192). Also, music, and more specifically the very popular black jazz of the time, had a key influence on animated cartoons. Bosko, the first Looney Tunes character, was a chipper little black man given to breaking out in song and strumming a banjo at any given moment. The problem as it relates to the issue of racism is that black characters are portrayed as lazy and shiftless at any time when no music is heard. Take for example the 1941 Walter Lantz cartoon “Scrub Me Mama with a Boogie Beat,” in which particularly racist stereotypes sleep the day away in Lazytown until a Lena Horne (?) look-alike sashays off a riverboat and motivates the lethargic populace to dance and shimmy. The message is that only music can energize black people.

Racist images in cartoons actually increased with the America’s involvement with World War II. Naturally, cartoons portrayed the Japanese and the Germans in an unflattering light. Take, for example, “Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips,” in which the Japanese are portrayed as yammering myopic, buck-toothed imbeciles. But blacks continued to suffer the brunt of the stereotyping, which might seem odd given that the United States was fighting a dictator who wanted to eliminate races he deemed inferior. Norman Klein links this increased racist imagery with the evolution of the chase cartoon. The war made cartoons more frenetic, more in keeping with a world at battle (188). Klein suggests that blacks in cartoons were in fact white people on the loose.

The war brought changes at home, particularly in Los Angeles, where most cartoons were being made in the 40s. The big cities experienced a large influx of blacks and immigrants coming in to man the factories fulfilling defense contracts. Inevitably the races clashed, sparking riots. On a more psychological note, human beings typically stereotype others different from them in order to allay their own insecurities. Klein also suggests that the racism in cartoons betrayed white people’s anxiety over modernization. Perhaps it was soothing to see the same images of an earlier time reinforced again, especially if framed within more frenetic pacing. Indeed, audiences might have felt strangely reassured upon seeing a familiar blackface after a calamitous explosion.

It is amazing how frequently the same gags were repeated. One might think that almost every black man looked like Stephin Fetchit . Any time something exploded near a character’s head or if he was doused with tar or ink, it was certain that the he would turn into a minstrel blackface with bulbous lips. Take just about any Tom and Jerry cartoon from the 40s for example. Anybody that traveled to Africa was guaranteed to find himself in a cauldron surrounded by dancing cannibals. Characters that were black to begin with were typically lazy, oversexed, and loved to gamble. In “All This and Rabbit Stew” Bugs Bunny easily lures a shuffling black hunter into a craps game.

What were the makers of the cartoons thinking? Did they have contempt for black people? Were they simply conforming to the norms of society at the time? Were they attempting to satirize racism? Did they mean any harm?

George Pal was a Hungarian artist who immigrated to Hollywood, where he founded George Pal productions and produced stop-motion animation under the banner of Puppetoons and Madcap Models. From 1942 to 1947 he featured Jasper, a little black boy whom a bad intentioned scarecrow and crow try to lead astray. Pal explained to Cinefantastic magazine in 1971 that he “had long been attracted to the folklore of the American Negro and believed it to be the richest and the most colorful in American History.” (Sampson 30). In 1946 Hollywood Quarterly took him to task for the Jasper cartoons, not so much for Jasper as for the scarecrow and crow who, in their opinion, embodied the worst aspects of racial stereotyping: Pal “perpetuated the misconception of Negro characteristics. When we are building a democratic world, it is libelous to present the razor-totin’, ghost-haunted, chicken-stealin’ concept of the American Negro.” (Cohen 58).

Ebony magazine printed a rather favorable article about Pal who, after all, had come from Europe in 1939 and that “as a European not raised on race prejudice, he takes America for what he finds in it. To him there is nothing abusive about a Negro boy who likes to eat watermelons or gets scared when he goes past a haunted house. But to American Negroes attempting to drown the Uncle Tom myth that Negroes are childish, eat nothing but molasses and watermelons and are afraid of their own shadow, Jasper is objectionable.” (Cohen 58). Apparently, Puppetoons is an example of an animator who was not intending to be racist. The criticism that he received much to his surprise indicates how history effects a perception of something as racist. The images themselves were not what was objectionable but how they tie in with the oppression of a race of people.

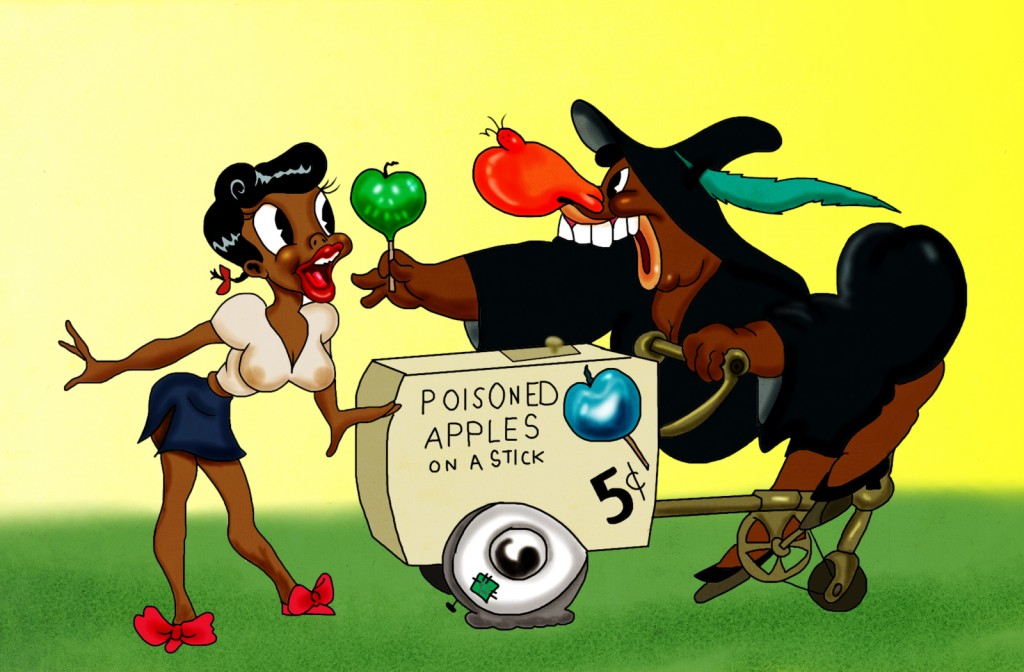

“Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs,” Bob Clampett’s seven-minute parody of Disney’s “Snow White” has been alternately celebrated and reviled. Clampett says that it is in part homage to the black music scene (Klein 192). He denies any racist intent. Black musicians such as trumpet player Eddie Beals helped script the gags. Black actors and actresses such as Vivian Dandridge, her mother Ruby, and Zoot Watson provided the voices. Prince Chawmin’s movements were based on those of a particularly elastic dancer that animator Virgil Ross witnessed in one of the black nightclubs the filmmakers attended in researching for the cartoon. The characters are grotesque in their stereotypical features. It is important to note that “Coal Black” is a wartime cartoon. The seven dwarfs are now in the army and it is only the kiss of the smallest dwarf that revives So White and its power is a “military secret.” Defenders of the cartoon cite the portrayal of black people participating in winning the war but who can say how hurtful the stereotypes are to black people.

It is also notable that the cartoon demonstrates that black characters could get away with doing things that white characters never could in film under the restrictive Hays Production Code. One scene strongly suggests that So White has engaged in some sort of sexual activity with the men of Murder Incorporated, sent by the evil queen to black her out. Apparently, the men in charge figured that black people were more immoral than whites and therefore could normally be expected to do things that whites would not and therefore it was permissible to show it. Maybe animators’ prevalent use of black stereotypes was a way to avoid the censors.

Precious little is known about what black people in the earlier half of the twentieth century thought of these cartoons, but history has provided us with one large example: Walt Disney’s feature “Song of the South,” released in 1946. Walter White, then executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sent this telegram to the press the day the film opened:

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People recognizes in Song of the South remarkable artistic merit in the music and in the combination of living actors and the cartoon technique. It regrets, however, that in an effort neither to offend audiences in the north or south, the production helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery. Making use of the beautiful Uncle Remus folklore, “Song of the South” unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts (Cohen 60-61).

Even while the Disney studio was making the film, Disney had to be clearly aware that he was risking a negative reaction. Records show that the Production Code Administration had warned him several times about using black stereotypes (Cohen 62). According to Ebony magazine, bandleader Tiny Bradshaw had been offered a part in the film “but turned it down, declaring it would ‘set back my people many years'” (Cohen 61). Clarence Muse, a black actor, was hired in 1944 as a story consultant regarding the portrayal of Negroes. He suggested that the studio present Negroes as dignified, prosperous-looking individuals. His ideas were rejected and he quit. He went on to inform the public that Disney was going to depict blacks in an inferior capacity and that the film was detrimental to the cultural advancement of the Negro people (Cohen 65). Maurice Rapf, coauthor of the film, believes that Disney hired him because he was Jewish and a communist (Cohen 63), suggesting that Disney hoped such credentials would stave off any accusations of racism. Rapf is reluctant to take too much credit for authorship as his ideas – making the white family poor, emphasizing that Brer Rabbit is an ethnically black character outsmarting the white characters – were absent in the final film. Despite the difficulty Song of the South engendered, it did make money and was re-released in 1956, 1972, 1980 and 1986. Nevertheless, Disney was finally persuaded to refrain from depicting black people in subsequent productions.

The years following World War II saw the demise of racist images in cartoons. Several possible reasons exist for this decline. The general population was becoming increasingly aware of the problem of racism. Theater owners perceived at some level that people would not watch movies they deemed offensive. Cartoons were becoming more expensive to produce and it was financially prudent to steer clear of anything that would potentially alienate any portion of an audience. It would also seem that advocacy groups were becoming increasingly vocal against racism. Note that the bulk of documented protests do not date until after the 1940s.

At the same time, a popular new medium was slowly eroding the theater audience. Cartoon studios found a new source of income in re-releasing old cartoons in their vaults for television. But first these cartoons needed scrubbing. For example, Mammy Two-Shoes, the black housekeeper in over a dozen Tom and Jerry cartoons, had her dialect voiced by a black actress named Lillian Randolph (Sampson 2) replaced with an Irish brogue voiced by June Foray (Maltin 302), an irony since Randolph was one of only three actual blacks who did cartoon voiceovers. White people imitating blacks did the vast majority of voiceover work for black characters. Blackface gags were edited out. Any cartoons where the black stereotypes were too pervasive to be edited, such as the Little Lulu series with Mandy the maid, were simply not shown. The studios have buried the worst offenders, never to be seen by anybody but the most persistent scavenger scouring the World Wide Web and then only in unpreserved, poor quality prints. It is all very well to censor offensive images but the result has been that blacks are rendered nonexistent. Nothing has replaced them. One could conclude that any depiction of blacks is offensive.

How does one reconcile the unpalatable and obvious offensiveness with the frequent brilliance of these cartoons? It is an uncomfortable question. It is up to the individual viewer to formulate an opinion. No doubt the feelings will be mixed. Whatever one’s response it is essential to acknowledge an unpleasant truth about the images one sees even if one finds them enjoyable.

For more information on racist cartoons please check out our post – The Censored Eleven – Banned Cartoons.

For more information on cartoons from the 1970’s that depict Blacks in a more positive light please check Funky Turns 40: Black Character Revolution, our Black animation exhibition, and our Black Animation Collection.

Source:

Author – Ruth Dubb

The Museum of UnCut Funk has reached out to Ruth Dubb via email for further comments on her article. We are still waiting to hear from Ruth and to interview her.

For more information on Ruth Dubb please visit www.ruthdubbafterdark.com

Bibliography:

Barrier, Michael. Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in its Golden Age. New York, Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

Cohen, Karl F. Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America. London: McFarland and Co., 1997

Klein, Norman M. Seven Minutes: The Life and Death of the American Animated Cartoon. New York: Verso Books, 1996.

Maltin, Leonard. Of Mice and Magic: A History of Animated Cartoons (New York: New American Library, 1980).

Sampson, Henry T. That’s Enough, Folks: Black Images in Animated Cartoons, 1900-1960. London: The Scarecrow Press, 1998.

4 Comments

Curious question- Are there any recent racist depictions of black/African Americans in contemporary animation?

Just sent this to PBS:

I sent this to the Wild Kratts page on FaceBook with no response:”Great news for you about the nominations; my daughter adores your show.But I just noticed that your black character, ‘Koki’ (who is listed variously as African or African-American) is played by a white actress. Now that would not be a problem in itself (I’ve heard many black actors playing white characters exquisitely) …but ‘Koki’ sounds like some white person’s idea of some blacksplotation version of an African-American via 1972 or something. It’s kind of gross, and, well, bad acting; hearing this interpretation of that character I had to check if the actor was simply bad at her job or… ‘oh my god — she IS white.’This is deeply offensive and that it’s so casually done is deeply painful and I’m not sure how to explain this to my daughter of 5 years old 10 years from now when she asks me why I stood by and let her watch some really weak stuff which could have been so great and is actually so obviously racist.Please address this, thank you, Joshua Wolf Coleman”

I noticed these black people have white borders around their lips.

That’s because the would put makeup on to make actors look black